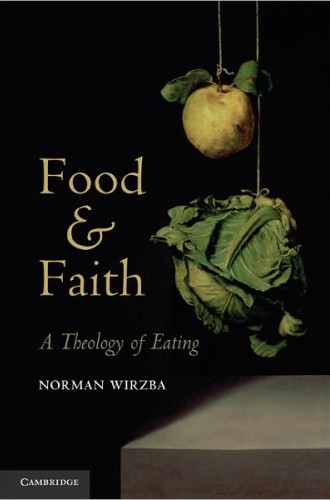

Food and Faith, by Norman Wirzba

Pastors have long known that there is more going on with food and eating than the mere filling of the stomach. We know that the Eucharist is more than bread, wine and people gathering around the Lord's table. If we've been pastors for very long, we also know that church potlucks are more than chicken and potato salad, and we know that something more goes on when a congregation feeds the homeless. Some of us are even learning that there's more happening with gardening than just raising corn. We know there's more, even though sometimes we might be hard-pressed to explain what the more is. Norman Wirzba's Food and Faith: A Theology of Eating helps us with the more better than anything else I've read.

Wirzba is research professor of theology, economy and rural life at Duke Divinity School and the author of The Paradise of God: Renewing Religion in an Ecological Age and Living the Sabbath: Discovering the Rhythms of Rest and Delight, the latter a lively and delightful read for congregations and small groups. He also serves as the general editor for the University Press of Kentucky's very fine Culture of the Land series, and he edited the first volume in that series, The Essential Agrarian Reader: The Future of Culture, Community, and the Land. Of the books he's edited, the best known is the Wendell Berry collection The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays of Wendell Berry, for which Wirzba's introduction is one of the best short introductions to Berry in print. Wirzba has established himself as a leading theologian in helping the church think about the connections between agrarianism, faithful discipleship and caring for God's creation. He has done so by combining insight, attentiveness and solid scholarly work with good, clean prose. It's not incidental that he's also a very fine gardener.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In Food and Faith, Wirzba asks with the first sentence, "Why did God create a world in which every living creature must eat?" By the second page he gives the short answer: "Eating joins people to each other, to other creatures and to the world, and to God through forms of 'natural communion' too complex to fathom." He wants us to know that we don't understand food until we realize that its origin and end is God and that every mundane act of eating is a daily invitation to commune with God and God's creation.

It's all about communion, community and membership, which are rooted in the triune God, within whom there is "no subordination or hierarchy. Rather, the Three share life with each other in complete mutuality;

. . . they always abide in each other." Wirzba explains the ancient doctrine of perichoresis as a kind of "mutual abiding" wherein the One is "making room in itself for the other." From the trinitarian God to the Eucharist, where we are able to participate in this trinitarian life, to gardening, where we imitate God by cultivating food while we are being cultivated in order to produce affections and forms of attention that make us "capable of communion," Wirzba sees food as one of the primary ways we enter into complex membership and communion with God, with each other and with all of creation.

But we live in exile, which Wirzba defines as "the refusal to welcome and accept responsibility for the membership of creation of which we are a part"; exile is alienation and isolation from communion. Exilic eating is when we eat poorly, in a way that is fragmented from a healthy food chain, which results in our various eating disorders, including everything from obesity to industrial agriculture, destruction of the environment and degradation of our food. Exilic eating is the opposite of eating eucharistically.

Wirzba discusses death, sacrifice and eating, briefly touching on different perspectives of vegetarianism and offering a wonderful reflection on feasting and fasting before bringing the reader back to the Eucharist, which provides the place of orientation on food and eating. In the final stretch he discusses gratitude and celebration, and he explains why saying grace at the table is important theologically and politically.

The concluding chapter, "Eating in Heaven? Consummating Communion," is worth the price of the book. In spite of Jesus' resurrection meals and food-related parables, such as that of the great banquet, I had not given much thought to whether there will be eating in heaven. Wirzba has thought about it, and he demonstrates that ancient thinkers like Tertullian and Augustine did as well. Wirzba says that if eating is about hospitality and intimacy (and not just about gobbling down something to assuage the latest hunger) and heaven is a place where eternal life is not so much about length as about the depth and quality of relationship, where relationship and membership are sites of healing nurture, then the possibility of eating in heaven begins to make sense. This is why when we eat well, in communion, we taste a little bit of heaven here on earth.

This book is full of ideas and themes that almost leap off the page into the pulpit and pastoral ministry. For example, Wirzba uses the wonderful phrase "being capable of communion" in several places. He introduces this phrase early in the book when he explains:

To transform eating into a spiritual exercise is to cultivate the practical conditions and habits—attention, conversation, reflection, gratitude, honest accounting . . . for us to see with depth and appreciate the gifted and graced character of the world. . . . We must be capable of communion, capable of entering into and seeing the value of a community that is not simply a collectivity.

When I read that, I immediately started thinking about how much of my pastoral work is helping people become capable of communion. They come in the door well schooled in a kind

of Tea Party spirituality that understands everyone as autonomous, and God and church as existing for the individual's spiritual consumption. Many want a truer communion in Christ but have no idea what it looks like, how to participate in it and how to sustain it. Even staying married creates a challenge. A great deal of my job involves preparing the ground, planting the seeds, caring and cultivating so people can eventually grow into membership and communion.

This tells us why Wirzba's work is so important to the church and why many pastors are reading agrarians like Berry, whose 1977 book The Unsettling of America is one of the starting points of what is loosely called the new agrarianism (in contrast to the old agrarianism of the 1930s). Wirzba writes to counter the destruction of land and farms and communities by industrial agriculture. He and other environmental writers, like Michael Pollan, have joined Berry, plant geneticist Wes Jackson and farmer Gene Logsdon to help us understand that agrarianism is a "compelling and coherent alternative to the modern industrial/technological/economic paradigm." Wirzba has said that agrarianism is not "a throwback to a never-realized pastoral arcadia" but "the sustained attempt to live faithfully and responsibly in a world of limits and possibilities." Or, as I've heard him say, "it's about learning to live as creatures."

Pastors see congregations being co-opted by this same industrial/technological/economic way of thinking, which turns churches into spiritual superstores, confuses evangelism with marketing, judges success by the profit margins of the "three Bs"—bodies, buildings and budgets—and sees speed and spectacle as the standards of worship. Pastors are looking for skills and insights to help us be faithful to Christ in our particular place, with our particular people, instead of becoming a franchise of the newest and biggest successful store/church. From Wirzba and Berry we can learn that local food, farmers' markets and local economies are places of ministry, and they help us recover our vocation to care for God's good creation. They also help us realize that agrarian lessons make good pastoral sense.

When I was a seminarian, a veteran pastor told me that you can tell a lot about a church by how much people linger with each other after worship. If church members hang around and talk until you have to turn out the lights and push them out the door, and then talk more outside, it's a sign of a good church. But if church is rushed and as soon as the Amen is sounded, they head out the door to their cars, with everyone going their separate ways, that's not a good sign.

Both agrarianism and the slow-food movement say that we will care about food (and all that goes with it, like Earth, the workers, farming and cooking) when we take time to linger, pay attention, listen and learn about how food is grown, produced, prepared and consumed. There is more going on here than pastors wanting to be farmers or gardeners. As Wirzba puts it, when we cherish God's gifts and savor and linger with God and with each other, our eating and our life together as the people of God can "rightly be understood as a 'rehearsal of heaven on earth.'"

When I was growing up in a small town in West Texas, every Sunday afternoon after church we went to my grandparents' house for dinner along with dozens of relatives and neighbors. Later, in the cool of the day, when everyone had gone home, I walked with my grandfather around the garden and among his peach trees. If he spotted a particularly good-looking ripe peach out of reach, it was my job to climb the tree and bring it down, and then we'd go over to the porch, where he sat in his favorite chair, propping his feet on the trunk of the nearby pecan tree (which leans to this day from 50 years of propped feet). Of course, I wanted to bite into the peach immediately, but he'd say, "There are some things worth waiting for." He'd pull out his old Case pocketknife and slowly peel that peach so that the peel was in one continuous swirl, and then he'd walk over and throw the peel to the chickens while I grew even more impatient. Finally, he'd cut a slice of that peach and hand it to me, then cut a slice for himself, and with the first savoring bite he'd say, "Boy, if that doesn't make you believe in heaven, nothing will." Between the garden, my grandmother's cooking, people everywhere, the walk and conversation and sharing of the peach with my grandfather, I believed every word of what he said.

According to the insights of Wirzba's book, my grandfather was a pretty good theologian.