Lesser-known heroes

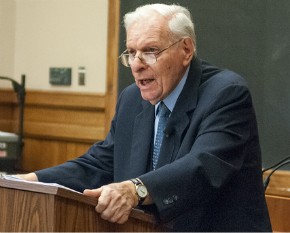

He has an unpretentious name—Ralph Hamburger. If you heard him say it at a party, you would be tempted to smile and look over his shoulder for someone else to greet. But the name fits him well. There’s nothing about Ralph that pretends.

He grew up in Holland, where his family was part of the resistance movement. They hid Jews. After the war he came to America, received a college education, and attended Princeton Seminary. He was ordained as a Presbyterian pastor and served a congregation here until he could return to Europe, where he spent the rest of his ministry pastoring underground congregations behind the iron curtain. There were very few days when he was not an outlaw, always in danger of being thrown in jail.

His life sounds similar to that of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who also left this country to enter the fray of a culture dangerous to his convictions. Everyone is ready to bow a knee at the mention of Bonhoeffer’s name, but precious few of us have heard of Ralph.