Fibbing about church

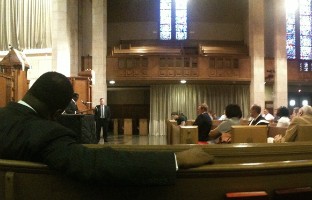

Church attendance isn’t what it used to be. Along with the general decline in religious affiliation, churches face another challenge: on any given Sunday, even those with strong connections to a church might well miss worship. This has practical implications for ministry, affecting everything from preaching plans to announcement strategies to how newcomers are welcomed; it also raises deep questions about what it means to be a church.

In a new study by the Public Religion Research Institute (see "Americans stretch the truth about attending church"), 70 percent of Americans told interviewers they attend religious services at least occasionally. Only 36 percent said they do so every week.

The study also makes a more startling claim: some of these people are exaggerating. The real attendance numbers are even lower.