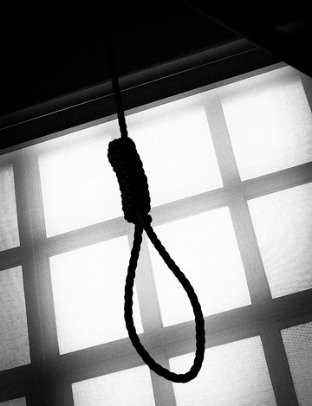

Motion to repeal: Against the death penalty

Last April, the Connecticut state legislature repealed the death penalty, making it the fifth state in the past five years to take that step (New Jersey, New Mexico, New York and Illinois are the others). Yet in November, voters in California rejected by a 53 to 47 margin a bid to repeal the death penalty. Those two decisions of 2012 reveal the conflicted state of national debate on capital punishment.

In all 17 states in which capital punishment is outlawed, the change has come through legislative action. Support for the death penalty generally remains high among voters—and may have even intensified over the past two decades. A 2011 Gallup poll found that only 27 percent of Americans think that executions are immoral—down from 41 percent in 1991.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

According to the Pew Research Center, the death penalty is endorsed by 77 percent of white evangelicals, 73 percent of white mainliners, 40 percent of black Protestants and 59 percent of Roman Catholics.

At the same time, an increasing number of people believe that the criminal justice system is unfair and worry about innocent people being executed. “There is a very, very high suspicion even among evangelicals of the death penalty and its practice,” said Bill Mefford, director of civil and human rights with the United Methodist Church’s General Board of Church and Society.

The North Carolina–based People of Faith Against the Death Penalty is working nationally on the issue, even as it continues to fight for reform and abolition in its home state.

“We view the religious community in the United States as a sleeping giant on this issue,” said PFADP executive director Stephen Dear. “If those religious communities that have been on record as opposing the death penalty since the 1950s actually prioritized this issue and mobilized their congregations, it would transform this movement, and it would speed the end of the death penalty by decades.”

In 2006, North Carolina went from having one of the most active death chambers in the nation to having a de facto moratorium on capital punishment. The reasons don’t have much to do with religious faith, but they do involve the mobilization of religious people.

What PFADP did in North Carolina, said Dear, was generate public interest in the issue, forcing judges and bureaucrats to scrutinize the system. “We changed the culture of North Carolina to where people raised questions about the death penalty,” said Dear.

It did this at a time when prisons and the North Carolina Medical Board battled over whether a physician could ethically preside over an execution and when the legislature was deciding it could no longer ignore evidence of racial disparities on death row.

PFADP used prison-house protests, statehouse lobbying and a massive rallying of grassroots support. Between 1999 and 2008, the group collected anti–death penalty resolutions from more than 1,000 churches, civic groups and businesses and from 39 different city, town and county governments. More than 50,000 North Carolina residents signed a petition calling for a moratorium. A moratorium bill passed the state senate in 2003 but died in the house.

Despite that defeat, the movement won several key reforms. In 2001, state legislators banned executions of mentally retarded convicts and created an Indigent Services Commission to make sure poor defendants have good lawyers. In 2004, it gave prosecutors the option of seeking a life-in-prison sentence even in cases where aggravating factors would have mandated death. In 2006, it created an Innocence Inquiry Commission to investigate claims of false convictions.

States that have repealed the death penalty did so, Dear pointed out, after years of not using it. When New York and New Jersey enacted repeal in 2007, neither had executed anyone since 1963. New Mexico last used lethal injection in 2001; it voted for repeal in 2009. Illinois repealed capital punishment in 2011, 12 years after its last execution. Connecticut executed a murderer in 2005 but had gone 45 years before doing so. Dear hopes that these examples might portend repeal not only in North Carolina but in California, Maryland, Montana and Pennsylvania—which have had no executions since 2006—and in Colorado and Kansas, which have had no executions since the mid-1960s.

Ben Jones of the Connecticut Network to Abolish the Death Penalty said that repeal succeeded in his state with the help of the families of murder victims. Many victims’ relatives signed a petition calling on the Connecticut legislature to repeal the death penalty. The families said that they have to endure a decades-long appeals process, and that the seemingly arbitrary decisions about whether to pursue the death penalty have the effect of treating murders that lead only to life in prison as less significant.

“Every murder is heinous, a tragedy for the lost one’s family,” the letter states. “The death penalty has the effect of elevating certain victims’ families above others. Connecticut should be better than that.”

“Their voices especially resonated with legislators,” said Jones, who started fighting the death penalty through Amnesty International’s clemency campaign for Troy Davis in Georgia, a case that galvanized the movement in the United States.

“Any reasonable person would come to the conclusion that there was a lot of doubt about Davis’s guilt,” said Jones. “They [government officials] were more willing to see an innocent person be executed than to admit their mistakes. This is not a power that the government should have.”

PFADP helped to collect signatures supporting Davis’s clemency from 3,500 faith leaders across the country. Even so, the state of Georgia executed Davis in September 2011.

“The only way to fix the death penalty is by ending it,” said Jones.

That’s why two years ago, PFADP launched its Kairos Campaign, aiming to collect signatures and resolutions from denominational bodies and individual congregations, much as it did in its North Carolina campaigns but this time throughout the United States.

“There’s no other organization that works specifically to mobilize people of all faiths on a national level,” said Mefford, who’s been working on the death penalty for the UMC for the past six years and joined the PFADP board in 2009, becoming its president last year. Mefford’s office has been working to educate Methodists about the death penalty and encourage them to speak out against it. The denomination has also been funding visits to churches by former death-row inmates who were later found innocent.

“We want to get them to speak at smaller churches in more rural places where there’s probably more of a need for education,” Mefford said.