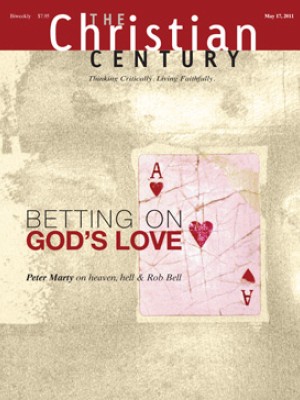

Something game-changing

When an attendee of Rob Bell's congregation said that he was certain that Gandhi is in hell, Bell responded, "Really? Gandhi's in hell? We have confirmation of this? Somebody knows this? Without a doubt?"

Some of Bell's evangelical brothers and sisters are horrified by his wavering on the doctrine of hell, and Albert Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, says Bell's new book, Love Wins: A Book about Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived, is "theologically disastrous." "When you adopt universalism . . . you don't need the church, and you don't need Christ, and you don't need the cross. . . . This is the tragedy of nonjudgmental mainline liberalism."

But Peter Marty, who writes about Bell in this issue, believes that Bell is on to something important—maybe even something game-changing. And as Bell himself says, "[I've] long wondered if there is a massive shift coming in what it means to be a Christian. . . . Something new is in the air."

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Something new is happening. Denominations are struggling to discover new ways to be church. New partnerships are formed between different Christians who share a common sense of mission, and people of every faith are struggling to relate to people of other faiths in a world that has brought us into closer contact than ever before. Within Protestant Christianity, Jim Wallis and Tony Campolo are examples of leaders who graciously reach across the old conservative-liberal theological divide to make common cause with others concerned for a just society and an authentic, respectful evangelism.

It distresses me when people on my side of the divide are accused of arriving at our theological and ethical positions out of a desire to be politically correct instead of out of vigorous study of scripture and theology. It's also a mistake to lump conservative evangelicals together and accuse them of narrowness and bigotry. I come to my positions on ordination and sexual orientation, reproductive choice, health care and relations with people of other faiths not in spite of scripture but because my study of scripture leads, nudges and prods me. Maybe both sides need to stop relying on generalizations and unkind accusations and give the other the benefit of the doubt, assuming that he or she takes scripture and biblical authority seriously.

Rob Bell is accused of universalism when he imagines Gandhi in heaven. Any of us is subject to the same kind of accusation whenever we suggest a little less certainty and judgmentalism about whom God finally favors and blesses. The point is that when some of us come to that new openness it is not because we ignore the Bible but because we are compelled by scripture's certainty about God's steadfast love, the amazing grace of Jesus Christ and St. Paul's assurance that in Jesus Christ, God intends to reconcile all things.

When the great theologian Karl Barth was charged with being a universalist, he reportedly denied it, but then quoted 1 John: "Christ died for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world." If you are worried about universalism, said Barth, "you had better begin worrying about the Bible."