Where our money goes: An itemized tax receipt

The Republicans are about to take control of the House of Representatives, and House leader-to-be John Boehner (R., Ohio) says their top priority will be creating jobs by cutting government spending. That's dubious as economic theory, but it's good politics: spending is unpopular, especially among the voters who powered the Republican takeover.

But what programs does the GOP want to cut? While party leaders have been clear about their other Tea Party-friendly plank—extend the Bush tax cuts, even for those who don't need the money and won't use it to stimulate the economy—they've remained persistently vague as to what significant spending cuts they favor.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

There's always more public support for the abstract cry of "let's reduce spending" than for actual cuts to individual programs. Self-interest plays a role here. The larger issue, however, is that people tend to have a pretty hazy sense of where their tax dollars go in the first place. This makes it easy to score points with nebulous pledges to cut spending but difficult to have a serious conversation about how the government spends our money.

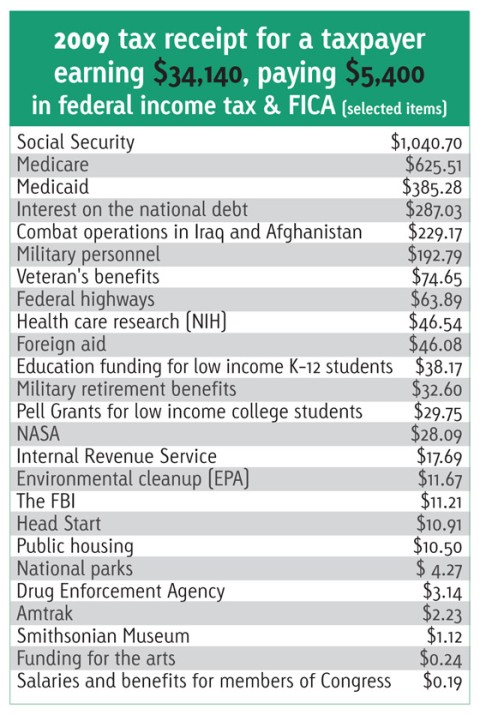

An idea from the think tank Third Way would help correct this situation. This centrist group has proposed that taxpayers be given an itemized receipt for federal income taxes and for FICA (the payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare). This could be done electronically at a nominal cost.

And speaking of nominal costs, a receipt could do a lot to counter, say, the widely held belief that a fifth of our tax dollars go to foreign aid. Actually it's about 1 percent—a number I came up with in ten seconds using Third Way's sample receipt and a calculator.

Income-tax receipts have been suggested before. But the rapid growth of electronic tax filing means they'd be even easier to implement. And in a political climate dominated by anti-big-government sentiment, having the facts about spending is more important than ever.

While GOP leaders have kept the spending-cuts talking points mostly vague, they did commit to ending congressional earmarks. Specific ideas have come from elsewhere in the conservative orbit as well. Republicans on the House transportation committee want to cut waste at Amtrak. The Cato Institute names public housing as one of a few "initial targets." As usual, lots of people would love to get rid of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Whatever the merit of these ideas, they don't add up to much in the way of savings. Even if we ended all arts funding and pork-barrel spending, let poor people pay market-rate rent and shut down Amtrak altogether, we'd save the average taxpayer about $29—the same amount that goes to NASA. If we can put a man on the moon and then, 40 years later, persist in spending far more on spacecraft than on passenger trains, we ought to be able to distribute a receipt that says so.

With an itemized receipt in hand, taxpayers would know that NASA's share of their money is 12 times bigger than Amtrak's. More important, they'd know that even the space program's slice is less than 1 percent of the entire pie. To really take on government spending, you have to address the behemoths at the top of the list: Social Security, health care and the military.

It's no secret that most Republicans would rather downsize entitlement programs than cut the military budget. But cuts to Social Security are opposed by a large majority of Americans. As for health care, everyone agrees that spending needs to be curbed—and this year's health insurance reform bill is a great start, primarily due to its Medicare cost controls. Yet the Republicans say they want to repeal the health-care bill—an idea that, like spending cuts, is a lot less popular with voters when the question is put in terms of individual provisions. You can see why the party's leaders don't want to talk specifics.

Some conservatives have made detailed proposals for major reductions in spending. The Heritage Foundation published a list of cuts the group claims would save roughly 10 percent of the federal budget. The list includes 90 ideas, 53 of which begin with the word eliminate. That's pretty ruthless, but at least it's intellectually honest. Slashing dozens of small and medium-sized items—Heritage's list includes the Community Development Block Grant, the Small Business Administration and AmeriCorps—is one way to seriously reduce the federal budget. The other is tackling Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and military spending head on. The multiple bipartisan deficit-cutting plans put out recently reflect this reality, with the additional option of increasing tax revenues.

Vague promises, however, don't amount to a plan. Instead, they capitalize politically on the fact that most voters are similarly fuzzy as to where exactly their taxes go. An itemized receipt would promote a better national conversation about government spending, one in which we could actually talk about how much programs cost—and whether they're worth it.