The glory of Epiphany

“It is arguably the least understood and least appreciated church season,” says Fleming Rutledge.

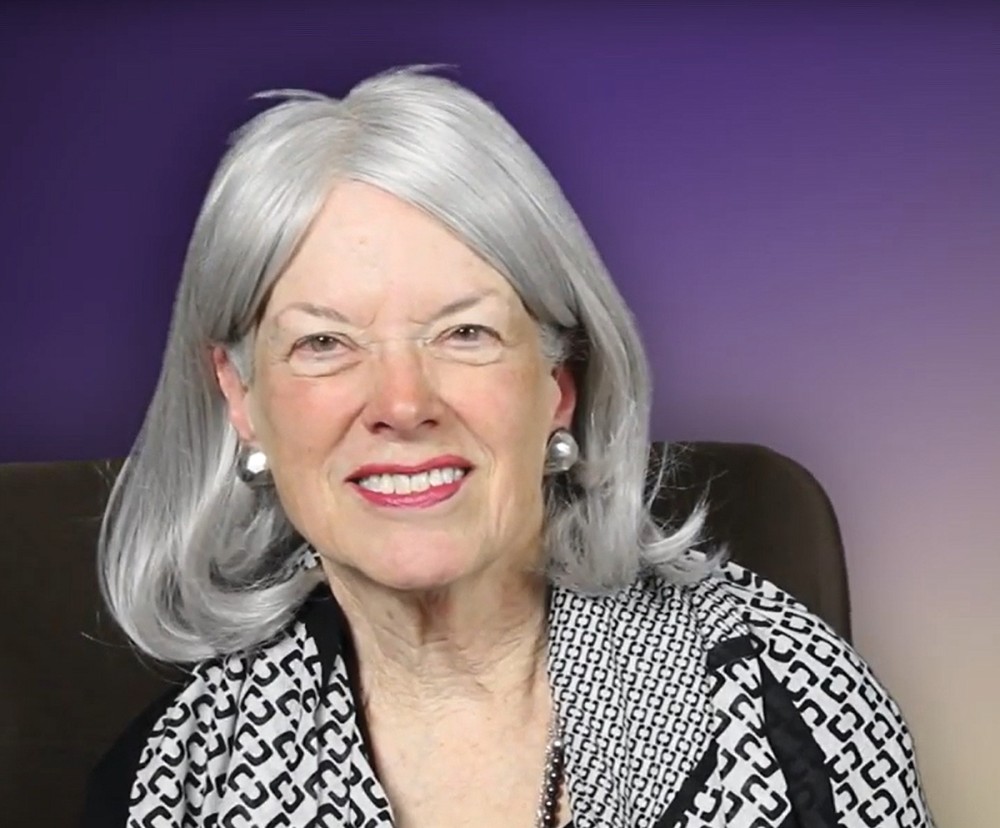

One of the first women ordained as a priest by the Episcopal Church, Fleming Rutledge is a renowned preacher and teacher. Her many books include the best-selling The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ. Her newest book, Epiphany: The Season of Glory, is part of InterVarsity Press’s Fullness of Time series, which aims to make the liturgical calendar accessible to those who are unfamiliar with it.

You write that this book is “intended not for academic specialists, but for everyone: pastors, church musicians, teachers, worship leaders, students, inquirers, anyone at all who wants to deepen their understanding.” How might people from traditions that have neglected the church calendar benefit from engaging the ancients’ attention to Epiphany?

The rhythm of the seasons, the repeating sequence of observances year after year, the variety of the scripture readings, and especially the larger story the seasons tell us in narrative progression—all these elements of the very ancient liturgical calendar are powerful for Christian formation. Attentive participation in the story that the seasons tell will deepen commitment to the gospel, the church, and especially the church’s mission—a traditional theme of the Sundays after Epiphany.