Self-evident truths?

What may have been obvious to Thomas Jefferson was probably not obvious to those he enslaved.

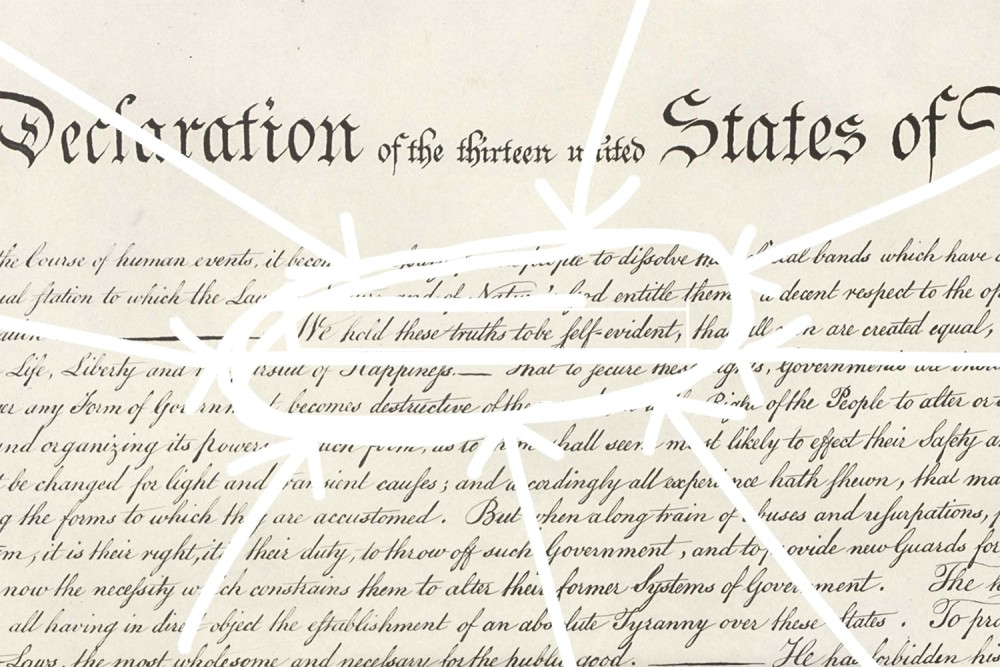

(Century illustration)

If you want to patent a personal innovation of yours for which you wish to secure the rights, you’d be smart to learn about the doctrine of obviousness. It’s the most fundamental principle of patent law and the most commonly litigated issue in patent infringement cases. Section 103 of the US Patent Act bars the patenting of any invention that would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the relevant field when the invention was created. This doesn’t mean every innovation must rise to the level of genius, or that old ideas assembled in new ways are prohibited from patent consideration. It only means that nonobviousness is a core requirement of patentability. The innovation must represent a substantial step beyond what is unmistakably evident, resoundingly clear, or plainly apparent to the ordinary mind.

In culture, politics, and everyday life, the obvious is often based on common sense. A set of values or ideas gains consensus to such a degree that serious people don’t bother questioning what they consider a settled matter that’s easily perceived or understood. A healthful diet and exercise yield healthier life outcomes than junk food and sloth. A Do Not Enter sign at the head of a one-way street can lead to tragedy if a driver willfully ignores it. Healthy relationships require respect. The results of a public election lacking serious irregularities deserve to be honored. These sorts of ideas all have the air of obviousness. They don’t need justification. They’re self-explanatory.

The United States was founded on an appeal to obviousness. When Thomas Jefferson holed up in a Philadelphia house for two weeks in June 1776 to draft the Declaration of Independence, little could he have known that schoolchildren 250 years later would commit his words to memory as part of their regular schooling. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” What could the slave-owning Jefferson have meant or intended by asserting that being created equal and being endowed with certain unalienable rights are self-evident truths?