We are all going to die

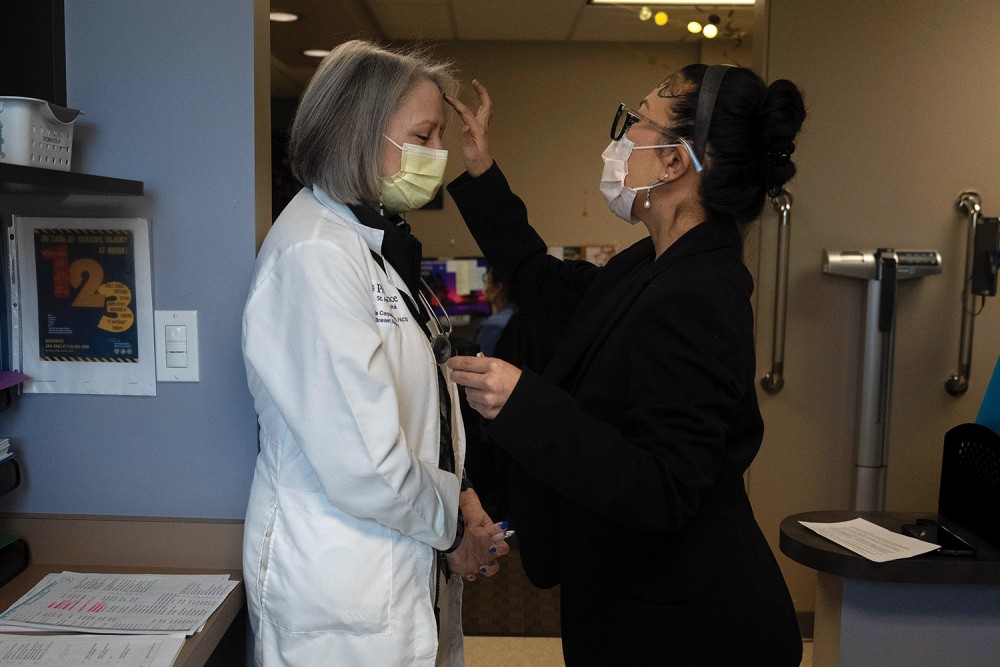

During my first several hours administering ashes as a hospital chaplain, I kept cringing.

Chaplain Angela Song, right, places ashes on the forehead of surgeon Michele Carpenter at Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California, in February 2023. ( AP Photo / Jae C. Hong)

Inside the vast, dimly lit chapel, I stand beside a stool that holds Q-tips, a number ticker, and a small jar of ash. The chapel is musty and dark, its stained-glass windows allowing little light to permeate the pews. It lacks a cross, bimah, or any other particular faith marker. This chapel is not a gathering place for a specific community but a refuge for the thousands of patients, family members, and staff who enter the Columbia University Irving Medical Center each day.

Nurses in navy scrubs begin to queue outside the entrance, and I ready a Q-tip in one hand and the jar of ash in the other. Then, as each person squats before my five-foot frame, I check their badge, make a black cross on their forehead, address them by name, and say, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Most of them murmur a thank-you and leave; a few walk past me to sit silently in the pews. One or two enthusiastically tell me how glad they are that the hospital offers ashes on Ash Wednesday. The mood, however, is mainly somber, and I wonder as I administer the ashes what these colleagues of mine—nurses and doctors and social workers—are thinking as they receive a sign of death on their bodies before making their way to the dying bodies they are caring for.

Ash Wednesday is the busiest day of the year for our spiritual care department. It’s a whole-team affair: the Catholic priest attends to specific sacramental needs, the chaplains who are comfortable with the imposition of ashes each cover an assigned part of the hospital, and those who are not handle the litany of calls and referrals that make up a day at the hospital. Like a symphony, it takes everyone doing their part to play the piece.

Last year, the day after Ash Wednesday I was sitting with my chaplain cohort when I saw a New York Times article about a man who was being investigated for hate crimes after multiple incidents in which he punched Asian Americans on the subway. I found myself suddenly in tears, unable to breathe—an intensely physiological response that was unusual for me. When my supervisor, a rabbi, realized what state I was in, she promptly invited me to accompany her and another chaplain friend to visit a colleague who’d gone into labor the day before. We made our way over to the maternity ward and held the beautiful baby. At the new mother’s request, we each spoke a blessing over the infant—one Jewish blessing, one Christian blessing, and one Indigenous blessing, representing each of our traditions. As we stood in the quiet, clean room blessing this new life that had entered the world on Ash Wednesday, my body calmed and I relaxed into the safety of my friends.

The mother, also a rabbi, now says that Ash Wednesday is her favorite non-Jewish holiday. She loves the personal resonance she feels with it as her daughter’s birthday, as well as the memory of the sacred moment of mutual blessing and respect that we shared the following day.

I, too, have come to love Ash Wednesday differently after two years of working in the hospital on this day. For me, the memory of being invited to provide a blessing in my own tradition to this daughter of a rabbi feels like the embodiment of interfaith chaplaincy. It baptizes this day with a kind of hospitality, marking it not merely as a day of somber repentance and meditation on mortality but also one of generosity and grace, a day that all can participate in regardless of their faith tradition.

The first time I administered ashes at the hospital, I was shocked both by how many people—patients, staff, visitors—wanted ashes and by the genuine gratitude and peace they seemed to feel upon receiving them. It felt incongruent to me, to feel peace at a symbol of one’s mortality: Why were they so grateful to have a stranger remind them that they will one day die? I felt as though I were saying, “Hello, good doctor—receive this sign that one day you will die just as inevitably as all your patients will.” I cringed for the first several hours that I administered ashes.

Then something shifted. I went to the pediatric ward and administered ashes to my patients, the children of parents desperate for hope and healing. I saw how this ritual gave them that hope and healing, the way their eyes closed, their heads bowed in gratitude, and their shoulders relaxed ever so slightly. I remember going into the room of a patient I’d been following for months, a five-year-old girl with leukemia, and feeling both a kind of dread and a strange, unexplainable grace as I marked her and her parents’ foreheads. It meant something—it meant everything, perhaps—that I, too, wore a cross of ash on my forehead as I marked theirs. I was not pronouncing their deaths like some kind of prophet or angel of death; I was joining them, and inviting them to join me, in the knowledge of our universal mortality. In a sense, I was saying, “We are all patients here. We are all going to die. We are all called to join Christ in his death and his resurrection.” Perhaps providing ashes on this holiday was the deepest embodiment of solidarity with sick and dying people that I possessed.

After that experience, I came to see administering ashes to staff differently as well. Rather than feeling like I was dooming the work of the doctors and nurses who came to me with their heads bowed—essentially telling them that no matter how hard they tried or how advanced medical science became, they would ultimately fail—I was relieving them of a burden too great to carry, one that medical providers are too often asked to hold. They are not, in fact, in the business of saving lives—not in the sense of endlessly deferring death, curing people of the disease of mortality.

Human beings cannot be cured of our mortal diagnosis; death will come for each of us at one time or another, no matter how healthy our lifestyles and how frequent our scans and checkups. Perhaps by administering ashes to these doctors and nurses, I was helping remind them of that truth, freeing them even a little from the enormous pressure that they carry. Their jobs are not to cure but to care, not to fix but to heal, until the inevitable and universal healing of our bodies comes in the form of the death we will all one day face.

According to the United States Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, physician and clinical services expenditures in 2021 totaled $864.6 billion. An estimated $4.3 trillion was spent on health care that year in the US, $1.3 trillion of it on hospital care. In 2017, a team of Australian health-care researchers reported that so-called futility disputes in that country—wherein patients with an extremely low or zero chance of recovery, such as those who are legally brain-dead, are kept on life-sustaining interventions in the hospital—cost $153.1 million per year.

The story behind these numbers is a complex one, and no single narrative can be extrapolated from it. Nevertheless, it seems clear that Western culture is too often a death-denying culture, one where the inevitable fact of our mortality stands in stark contrast to the billions of dollars spent each year not only on medically futile treatment but also on the many products aimed at denying death, halting the aging process, and alleviating the sting of acknowledging that we are mortal creatures. We know that we will die, but like children who cover their ears to ignore their parents’ commands, we block out the noise of our impending death with any device or entertainment we can find.

Distracting ourselves from death is not necessarily a bad thing. Human beings weren’t designed to dwell endlessly on our mortality, to read constant stories of violence and death on the news and ruminate over the inevitability that our loved ones will one day leave us. Jesus himself, even as he set his face toward Jerusalem and the violent death he knew would come, broke bread with his disciples, debated with his neighbors, and spent hours reclining after supper with friends and strangers.

Nevertheless, there is a difference between appropriate distraction and endless denial, and research has shown that such denial has enormous costs, from medical expenditures to the quality and length of one’s life (Atul Gawande makes this argument powerfully in Being Mortal). For my part, I have come to see Ash Wednesday, with its blunt liturgy and embodied rituals, as a profound antithesis, perhaps even a kind of antidote, to the particularly American denial of death. I now see the hospital setting as a uniquely appropriate stage for the drama of ashes, and its actors—the patients, families, and staff—as the people who have the most to teach us about how to live well as mortal beings, which is above all a question of how to die well.

The dramatization of death in the hospital that happens every year at the start of Lent leaves no room for escape, whether one wears a cross of ashes or shares a room with one who does, whether one is receiving a diagnosis or delivering one. We all bear witness with our bodies to the truth of our finitude, and for one day every year, perhaps we can help heal one another of our tendency to forget. There can be a grace to remembrance, after all. We remember that we are dust and that we will return to dust, and by remembering, we invite ourselves and one another to learn how to live in this fatal time between.