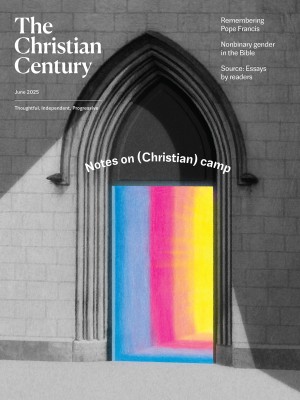

Notes on (Christian) camp

Move over, pink flamingos. For me, the cross of Christ is as campy as it gets.

Century illustration (Source images: Getty and Creative Commons)

When Jesus finally arrives in Bethany in John 11, he discovers that Lazarus has been dead for four days.

If only you’d gotten here sooner, says Martha.

If only you’d gotten here sooner, says Mary.

The tragedy is too much to bear. Their brother’s death could have been prevented.

Jesus asks where he can find the body of “he whom [he] love[s].” Mary and Martha take him to the grave.

And then it happened.

“Jesus wept.”

Wept for what reason? Regret? Should he have acted before Lazarus died? Or has the community’s grief become his own, such that he begins to cry their tears?

We often point to Jesus’ weeping as a sign of his full humanity: Jesus experienced the full range of human emotions. It’s understandable that in a scene of immense human suffering, Jesus would be moved to tears.

But I wonder: Did his tears flow from grief? Or is it possible that these were the kind of tears that come from laughing hysterically?

Haven’t you ever been caught in the throes of a laughing spell at the worst possible time? Haven’t you ever been at a funeral when something’s gone wrong—the pastor lets loose a Freudian slip, the church lady in the big hat two rows in front of you passes gas—and you, through tears, fight back your laughter? Don’t you know what it’s like for laughter to overtake you so quickly that all the fluid in your body rushes out of your eyes?

This is how I imagine Jesus weeping for his friend. Sure, his tomb has a certain stench, Jesus thinks to himself, but he smelled worse when he was alive. Oh, Lazarus.

In the conclusion to Orthodoxy, G. K. Chesterton reflects on a particular quality of Jesus’ that is sometimes missed: “There was some one thing that was too great for God to show us when He walked upon our earth; and I have sometimes fancied that it was His mirth.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Jesus is funny, but his humor is easily missed. That’s because he’s got a knack for a particular kind of humor. His laughter is for those who are in on the joke—and while Jesus invites everyone to be in on the joke, not everyone chooses to be. Those who remain outside the joke don’t have “ears to hear.” They see Jesus weeping at his friend’s grave, and they imagine he’s simply sad.

Jesus knows the old saying, “We sang a dirge [for you], and you did not mourn” (Matt. 11:17, NIV). That doesn’t bother him—he continues to laugh when people expect him to cry. Like those of us who laugh at funerals, Jesus laughs at the wrong times and places. He laughs while he cries. Because he cries.

“Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh,” he says (Luke 6:21). The Greek verbs in this sentence clarify that Jesus is promising future laughter to current mourners. And yet, as Jesus never tires of telling people, the kingdom is already here.

“If it is by the finger of God that I cast out the demons,” he says in Luke 11:20, “then the kingdom of God has come upon you.” Jesus is the bringer of God’s kingdom. To accept Jesus, to welcome his ministry, to laugh at his jokes, is to live into his Father’s kingdom. Jesus is God’s laughter, and those who laugh with him have already been snatched away into his Father’s realm.

If we read this beatitude in the context of Jesus’ overall ministry, the point becomes clear. Weep now, laugh later, sure. But also: Weep now, laugh now. Do both. Laugh while you cry. Go to Lazarus’s funeral and lose it. Hear the dirge and fall apart!

Jesus is God’s laughter, and those who laugh with him have already been snatched away into the kingdom.

There’s a name for this kind of inappropriate laughter: it’s called camp. One of the first definitions of this elusive term, from novelist Christopher Isherwood, is “making fun out of” something serious. We’re not making fun of it. Heavens, no! We’re taking the serious seriously; we’re just not letting it take us. To do this is to be a camp; yes, camp is simultaneously adjective, verb, and noun.

Susan Sontag was one of camp’s first commentators. In “Notes on Camp,” her now-classic 1964 essay for the Partisan Review, she says that by throwing the serious world in quotation marks, we are able to enter a new relationship with it. It’s not a Tiffany lamp, says Sontag, it’s a “Tiffany lamp”; the quotation marks signal not that the thing isn’t what it is but that it’s more than what it is.

Clear? As vintage milk glass.

My wager in this essay is simple: Chesterton was more right than he knew. Jesus is funny, but everyone misses it. Well, not everyone. Those with “ears to hear” get what he’s up to. Like your favorite neighborhood drag queen, Jesus is fabulously camp.

In the series of notes that follow—a method I’ve shamelessly cribbed from Sontag; thanks, doll!—I’m going to invite you into the joke.

1. “The whole point of Camp,” says Sontag, “is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to the serious. One can be serious about the frivolous, and frivolous about the serious.” Elsewhere, Sontag says that camp is “a seriousness that fails.” This is my starting point: camp dethrones, throws off, does something to the serious. That is the serious work it’s up to.

2. What is camp? This is the wrong question. Camp does not have an is. Camp does. Camp camps. The better questions, then, are when does camp happen? What are the conditions under which camp camps? Where does one go camping? Also, who is it that goes camping?

3. Many of camp’s foremost experts try to explain the sensibility by compiling various catalogs of camp people, artifacts, and movements. For Sontag, this catalog includes Scopitone films, Swan Lake, Aubrey Beardsley drawings, the National Enquirer, etc. Richard Dyer’s list also includes Beardsley, along with Vienna waltzes, Busby Berkeley, the Queen Mother, etc. Philip Core’s catalog includes Cole Porter, Hinge and Bracket, Marcel Proust, etc.

Fabio Cleto, who wrote a companion essay for the 2019 Met exhibit Camp: Notes on Fashion, put a twist on the catalog tradition and invited readers to imagine camp as a “fancy dress party” attended by the likes of Charles de Gaulle, Tilda Swinton, Caravaggio, the Rockettes, Mae West, etc.

What do all of these lists have in common? Voila! That’s camp, love.

4. Even if you are unfamiliar with most of the entries on the above lists, there’s one that I’m sure you know about: etc.

Camp is always etc. Its encyclopedia is always unfinished. Every attendee at camp’s fancy dress party will show up with a plus one. It may be this etc., this moreness, that makes camp camp. “The exuberance,” says Cleto, “marked by this suspensive stance, embodying the principle of incessant movement and endless listing, may well be camp’s definitive mark, the emblem of its incessant movement and shifting borders.”

Camp is never just what it is; it’s always more than what it is. Camp knows that reality is constituted by its potential, that what is the case is what might be the case.

Which is, of course, a theological claim.

5. You’re confused. OK. Let’s start at the beginning.

Look over there, at Mary Lou’s front yard. Do you see, next to the garden gnome, the pink flamingo? I see it too. So does camp. Which means we are no longer looking at a pink flamingo, but a “pink flamingo”—the quotation marks signaling that there is something more going on, that the pink flamingo is more than what it is. To see its etc. is to believe—and camp is a credal faith—that the being of a phenomenon is constituted by its possibilities.

Sontag says camp “sees the world in quotation marks,” which means camp is always on the lookout for etc., for more, for the future, for multiple futures. To throw something in quotation marks is to refuse to take it on its own terms, to refuse to take it—what’s the word? Oh yes: straight.

6. Camp throws everything in quotation marks, but it takes particular pleasure in doing so to suffering, pain, and horror. As anthropologist Esther Newton learned when she studied female impersonators in America, drag queens have “a tendency to laugh at situations that to [her] are horrifying or tragic.”

Examples abound in modern American gay history, but perhaps the most poignant (and shocking) comes from the AIDS epidemic. As scholars like David Halperin note, some HIV-positive men looked into the face of their illness and laughed. Not politely. No, this was the kind of laughter that onlookers find deranged.

Read, for instance, Robert Patrick’s 1987 one-person play Pouf Positive, about Robin, a flamboyant gay man suffering with, as it was originally called, “gay-related immune deficiency.” The entire play is an extended phone call between Robin and one of his exes, Bob, who is, according to Robin, so ugly that he’s going to survive the crisis: “Of course you haven’t got it; who’d give it to you?” These kinds of jokes are all over the script, gems like: “AIDS! Oh, doctor, thank God; I thought you said, ‘Age!’”

Another example: the Fire Island Widows, whom Halperin has written about extensively. These Italian-American gay men publicly grieved the loss of their friends and lovers to AIDS—while dressed as Sicilian women in mourning. Although they were comic spectacles, they were not mocking their own mourning. They weren’t not grieving. They were more than grieving. They threw their suffering in quotation marks, as Halperin puts it.

Camp, says Sontag, “does not cover up, it transforms.”

7. Camp is flip and irreverent. It lifts up its skirt to turn the other cheek.

8. The campy instincts of gay men can be found bubbling up in other cultures, too. “Camp is to gay what soul is to black,” says Dennis Altman: the two sensibilities perform similar functions for marginalized groups. In The Spirituals and the Blues, James Cone characterizes these musical forms as fundamentally about “the power of song in the struggle for black survival.” Reflecting on the Black folks he grew up with at Macedonia AME Church in Bearden, Arkansas, Cone writes,

Everything they did was a valiant attempt to define and structure the meaning of blackness—so that their children and their children’s children would be a little “freer” than they were. They had a “hard row to hoe” and a “rocky road to travel,” and they made it and intended to make it “through the storm.”

To sing the blues isn’t to deny your suffering but to take it up, to zhoosh it, to put it to work.

9. Camp strategically deploys laughter to recover the dignity of the oppressed. Camp humor isn’t synonymous with jokes or wit or sarcasm. It is rather a lighthearted, almost detached mode of relating to something serious. David Bergman calls camp “the voice of survival and continuity in a community that needs to be reminded that it possesses both.” Newton calls it “a strategy for a situation”—a situation of illness, oppression, or suffering.

These things are serious, and we ought to take the serious seriously. But there is no reason we need to let the serious take us. Camp is our strategy for not letting that happen.

10. Remember: When we camp, we make fun out of suffering, not of it. When we put our suffering in quotation marks, we remind ourselves that suffering happens, but that we also happen, and we can happen right back to our suffering, on our own terms. To do so is to respond to suffering with freedom and creativity.

11. “The courage to laugh is rooted in the God who appears when God disappears in the anxiety of seriousness.” Or whatever it is Paul Tillich said.

12. For many commentators, the camp object par excellence is the pink flamingo. For me, it’s the cross. Or rather, “the cross.”

Now we’re getting to it.

13. The cross of Christ is as campy as it gets. When Sontag says that camp “finds success in certain passionate failures” and that it calls something good “because it is awful,” she sounds an awful lot like certain New Testament writers talking about a cursed man hanging on a tree.

Jesus’ death is gruesome, barbaric, and bloody. The cross of Christ is awful; that is its seriousness. And yet, it is a seriousness that fails. Not that the cross itself fails. The cross succeeds in what it sets out to accomplish: Jesus’ murder. The murder itself, as most murders go, is tragic. But the seriousness of that murder is precisely what fails.

Because three days after Jesus is murdered on a bloody Roman cross—and I’m sorry to give away the ending—God shows up at the tomb with quotation marks.

14. Like Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus, God shows up at the grave of his beloved son, and he begins to cry. As he does so, he remembers one of Jesus’ favorite sayings: that those who weep will laugh.

So he decides to do both: to mourn a death and to dream of what might come next. God takes the serious seriously, but he does not let it take him. God decides to respond to suffering on his own terms, which are terms of life, love, and transformation.

God sees the broken, garbled body of his beloved son and invites him to become more than dead. And the corpse must be in on the joke, because he starts to laugh and laugh and laugh, so vigorously that his tomb splits open and he straightaway runs to play a trick on his old pal Mary.

15. Every camp has a friend named Mary. And every Mary is a camp. I don’t make the rules.

16. The resurrection is confirmation that Jesus is, in fact, more than what he is; the quotation marks have been there the whole time. The moreness of the cross reveals Jesus’ own etc. He has always been the resurrection and the life, has always been who he might become. Christ’s identity is confirmed from the future and has a retroactive effect on everything that precedes it. When he walks out of the tomb, he is “Jesus,” to the glory of “God.”

17. A campier way of writing the creeds would be to say not that Jesus and God share the same divinity, but that they share the same quotation marks. But no one consulted me.

18. If Jesus’ resurrection demonstrates that God is a camp—by “calling those things which are not as though they were” (Rom. 4:17), that is, by declaring Jesus more than dead—Jesus’ ministry demonstrates that he shares his Father’s sensibilities.

19. Jesus has certain tendencies, certain intensities. He’s twerking to the beat of his own drum. He doesn’t dance when he hears a flute; he doesn’t mourn when he hears a dirge. He gyrates like an attendee of a silent disco: onlookers can’t imagine what kind of music is blasting through his headphones. They can, however, see him moving. We can, too.

“The story of Jesus,” notes Luke Timothy Johnson, cannot be discovered “in a collection of facts or in terms of a pile of discrete pieces, but in terms of pattern and meaning.” There is, in other words, a character that emerges from the gospels, and we locate this character in his style.

20. When the New Testament says that Jesus is the image of the invisible God (Col. 1:15), it means to say that Jesus is God’s very style. Jesus is how God does what God does. It’s as if someone asked God, “What are you like?” and God responded, “There was once a man from Galilee. . . . ”

21. Christology isn’t ontology; it’s aesthetics.

22. To see Jesus’ face is to see God’s; to touch Jesus’ garment is to feel God; to admire—or be shocked or scandalized by—Jesus’ style is to be disrupted by God’s own way of being in the world.

Jesus, in his very embodiment, “venture[s] to live now out of the kingdom,” as Leander Keck puts it. “This means that from Jesus’s style, no less than from his words, one infers the conception of God’s kingship of which it is the reflex.”

To refer to Jesus’ style, says Keck, is to refer to “the contour of his kingdom-shaped life.” Jesus’ style is the kingdom of God; the kingdom of God is Jesus’ style. If, as Wolfhart Pannenberg said, “the deity of God is his rule,” the divinity of Jesus is his kingdom-ing: his way of being is a way of kingdoming. Jesus is, as Origen memorably put it, the autobasileia: the kingdom itself, the self-kingdom, the one who kingdoms.

To admire Jesus’ style—or to be shocked or scandalized by it—is to be disrupted by God’s own way of being in the world.

23. Too much theology—back to camp!

Each of camp’s commentators offers a list of characteristics that make camp what it is. There are qualities that persist throughout most of its performances. These are, in no particular order, incongruity, transformation, humor, exaggeration, and marginality. There are others, of course, but we’re at note 23 and I’ve got to pick up the pace.

24. “Incongruity is the subject matter of camp,” says Newton. Incongruity happens when two phenomena that are not usually considered together are juxtaposed. A pink flamingo in front of a trailer. A lamb standing though it has been slain. In both cases, something is out of place.

Camp performs at the intersection of an incongruity, inhering “not in the person or thing itself but in the tension between that person or thing and the context or association,” says Newton. The four examples she gives are high/low, youth/old age, profane/sacred, and cheap/expensive. We can find all four in the gospels: Jesus blesses the lowly, gives the kingdom to children, doesn’t mind when his disciples pluck wheat on the sabbath, and allows expensive oil to be wasted on his feet.

Jesus seems mad about incongruity. The first shall be last. A servant will be the greatest of all. If someone wants your outer garment, give them your underwear as well. Did he smack your left cheek? You have a right cheek, don’t you? Does she hate you? Love her fiercely. Does it seem like Rome is inheriting the earth? I’ll let you in on a secret: they’re not. You are.

We also see incongruity in his detached attitude to the seriousness that confronts him. He doesn’t respond with the gravity that we think a situation requires. Jairus’s daughter is on her deathbed, and Jesus stops to perform a completely unrelated spectacle. Lazarus is about to die, and Jesus takes his sweet time returning to Jerusalem. Jesus does not fittingly correspond to the situations in which he finds himself. It is not, however, that he’s completely detached from reality. He’s just attached to a different reality: the future God will bring about.

25. Camp is giddy about potential. When baptized in quotation marks, a thing becomes something else, something more. Sontag says camp is obsessed with “things-being-what-they-are-not.” Camp looks at an is and sees a could be.

This is the way Jesus sees the world. Water, to him, is already the wine it might become. Edward Schillebeeckx sums it up: Jesus’ sole “concern is with the potential, for the future, in the ‘now’ of the metanoia.” When Jesus looks at the world around him, he sees his Father’s kingdom—which is not here but also here.

26. Much of the camp humor that I hear in the gospels is in excess of language. The gospels are clear: they are accounts of Jesus’ sayings and deeds. Imagining Jesus’ facial expressions, gestures, body language, etc., breaks us free from scholarly practices that would try to confine Jesus to a few of his sayings. By overemphasizing Jesus’ style, his how, we might be able to hear and perform some of the more puzzling or embarrassing aspects of the Jesus story with freshness and creativity.

27. Jesus is melodramatic about pretty much everything (except the things you should be melodramatic about, like death and taxes). Do you want to be my disciples? Great, you’re going to die, and it’s going to be terrible. Want to go to heaven? Great, give away literally everything you own. Trouble with lust? Rip your eyes out right now. I’m waiting.

Chesterton was right when he said Jesus’ way of speaking “is quite curiously gigantesque—it is full of camels leaping through needles and mountains hurled into the sea.” Jesus exaggerates everything. Fine, sometimes he heals people discreetly, but usually he makes a show of it. “Stand up now!” he tells people who cannot, in fact, stand up. “Who touched me?!” he shrieks, when a poor hemorrhaging woman quietly brushes the hem of his garment. And let’s not forget the time he spat on a blind man’s eyes.

28. To be camp, says Mark Booth, is “to present oneself as being committed to the marginal with a commitment greater than the marginal merits.” A fine description of Jesus’ ministry.

Jesus was a down-on-his-luck Jew preaching to other down-on-their-luck Jews living under Roman rule. Notwithstanding the relative peace that characterized Galilee at the time of Jesus’ life, Jesus and his friends existed as a cultural and religious underclass. And it was to this group of outsiders that Jesus spoke a word of blessing.

Scott Long writes that camp “still asseverates a kind of hope: it is a system of signs by which those who understand certain ironies will recognize each other and endure.” Camp is laughter for those with ears to hear. Camp is in the eyes of the beholders, in the mouths of the community that has lost its collective voice.

Camp is a way of being together in the world for those who often find themselves on the outside looking in. Camp is a sensibility that is learned on the periphery, and it is put to practice in order to make the periphery the place to be.

The kingdom of God will one day swallow up the world, but for now it is over there in that tiny corner.

29. A word on gender. As Halperin points out, “before ‘camp’ was the name of a sensibility, it was the designation of a kind of person.” Camp originally referred to a camp.

A campy man is an effeminate man. Think Jack McFarland from Will and Grace or Albert Goldman in The Birdcage. I have fallen into this category of gay man at least since my sixth Christmas, when I performed a ravishing lip-synch to Barbra Streisand singing “ji-ji-ji-ji-ji-ji-jingle bells, ji-ji-ji-ji-ji-ji-jangle bells” in my grandmother’s basement.

But it isn’t effeminacy that makes camp camp; it’s the masculinity-transformation that the camp performs in real time. As Richard Dyer points out, “camp is not masculine . . . not butch.” Camps put the masc in mascara. At Stonewall, my people threw not fists but fabulous handbags.

Said differently: camp’s celebration of male effeminacy exposes the contingency of male masculinity. If men can perform as women, then they can also perform as men. Which means, well, masculinity is one giant drag performance—even when the performer happens to be a man.

It’s this kind of send-up that Jesus performs on divinity. Sure, Jesus codes God male, like when he calls him Father. But in key ways Jesus also resists popular conceptions of divine maleness. Caesar is male; God, who images forth both male and female from God’s own divinity, is beyond all gender. What’s important isn’t that Jesus from time to time uses feminine imagery for himself and God but that he, like a drag queen, chips away at masculinity’s constructs in front of an audience. Kings ride into Jerusalem on horses? A colt will do just fine. Kings draw their swords? No thanks; we aren’t ogres. We’ve been calling it God’s kingdom, but if Jesus is its agent, then perhaps we should call it a Queendom. Jesus is not like other male deities. He’s gentle, tender, compassionate, silly.

30. In this essay, I’ve been offering you a camp performance about a camp performance. I don’t think Jesus is as campy as Oscar Wilde, but I don’t think he’s as straight as Olive Garden, either. Jesus is a person who throws everything in quotation marks. Sickness. Mustard seeds. Death. The sabbath. If I’m going to call myself a Christian, then I need to follow his lead and throw everything in quotation marks. Including, yes, “Jesus” himself.

31. At the end of the day, even the most serious New Testament scholar has to admit that Chesterton was onto something. There’s a lighthearted quality to Jesus. He knows that at any moment, the Spirit might act and cause a person to be born again. Why judge who they are right now? To do that—to offer a judgment on who someone is—is to deny the power of God’s inbreaking future. Who knows what any of us might become when God visits us? Judge not, then, because to do so is to make a mockery of the one who makes everyone (yes, even the worst of us) new.

We are all who we might be.

32. Camp: hope.

33. The resurrection of Jesus, which throws the cross in quotation marks, confirms that Jesus always was a camp. In word and deed, in parable and act, Jesus confirms that this world is more than what we believe it is. More, even, than what the world believes itself to be.

34. “Every style is a means of insisting on something,” says Sontag. This is especially true of Jesus’ style, which insists on one thing and one thing alone: the kingdom of God.

Or, if you will, “the world” that God and his campy Jesus are crazy about.

35. There is no good way to end an essay on camp. The words “It is finished” no longer mean what they mean.

Brief portions of this article appear in the author’s Expository Times article "Doodling in the Style of Jesus.”