|

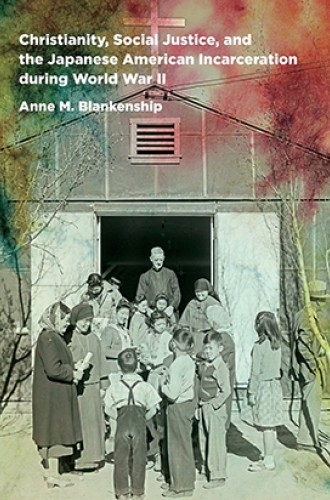

When immigrants are demonized, how does the church respond? |

What Christians did—and didn’t do—about the Japanese internment.

During the presidential primary season of 2015–16, Donald Trump called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.” Shortly after his inauguration, he issued an executive order calling for a temporary ban on immigration from seven majority-Muslim countries. Critiques of the executive order frequently pointed to disgraceful examples of similar incidents in American history, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and, more recently, the infamous Executive Order 9066, by which about 120,000 Japanese Americans were compelled to enter internment camps during World War II.

The internment camp experience has been the subject of excellent studies by Roger Daniels and other scholars. But one aspect of this story has received little attention until now: the considerable effort on the part of some American churchpeople to minister to Japanese Americans in the camps, as well as the dilemmas inherent in that effort. Anne Blankenship’s work opens up that story with skill, deep research, and compelling storytelling and analysis. It’s certain to become the definitive work on the subject. And it compels thought on how to respond to the current hysteria around other immigrant groups perceived to be disloyal.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Blankenship’s work focuses on a minority of American Christians. As she makes clear, “most congregations did not offer aid,” and most churchpeople accepted Japanese incarceration. While Quakers brought to this issue their legacy of antiracism, the Federal Council of Churches prior to the war had primarily conceived of race in America as a black-and-white issue and not a “foundational problem within American society.” The wartime experience of responding to the internment—at first through direct ministry and later through protest—did much to broaden conceptions of race as indeed a foundational problem. It also shaped the civil rights movement to come.

Initially, few Christian groups condemned the incarceration. “Mainline Protestants and Catholics showed reluctance to oppose government decisions during a time of war when ‘patriotic’ fervor ran so high.” Interned Japanese Christians, meanwhile, “found solace in their faith and sought biblical parallels to help explain their situation.” Amazingly, as the book details, many later remembered with considerable gratitude how the wartime experience deepened their faith and gave them a chance to bond with fellow Japanese Christians.

After the war, attempts by mainline white Protestants to foster integrated churches mostly flopped. By then, Japanese Christians, like black Christians after the Civil War, looked to their own churches to be places of solidarity, comfort, and equality that white-run churches simply could not provide.

Blankenship fascinatingly details one place, Arkansas, where white people regarded the internees on a more equal basis than they regarded the local black residents (whose loyalty was, presumably, not in question). In one instance, camp officials staged a minstrel show in which white people and Japanese internees appeared together on stage, all in blackface.

The war years also saw efforts from pacifist and left-wing groups to organize on behalf of Japanese Americans. The Fellowship of Reconciliation, for example, hired Perry Saito, a Japanese American from Washington, who told audiences that “all we want is to be recognized as Americans . . . You can be Americans even though you have a face that looks like an enemy.” Meanwhile, the FBI surveilled Saito, suspicious of his pacifism. And as the war progressed, a gulf grew between progressive Christian leaders and average American Christians on issues of race generally, and over the internment experience in particular.

Most Protestant leaders worried that too public of a protest would alienate parishioners. They thought it better to enlist sympathetic people behind the scenes rather than make public proclamations about the injustices done to Japanese Americans. Churches mostly worked to provide material and spiritual aid to interned people. But the receiving of that aid “reaffirmed the Japanese Americans’ lower social status and their sense of obligation to the outside churches.” Nonetheless, Japanese Christians moved Americans toward a more pluralistic conception of religion and race, in part by “radically allying the values of Buddhism and Japan with American Christianity.”

In 1943, as the Japanese people were released from camps, progressive church leaders thought integrating them into white-run churches would be the answer to segregation and the path to assimilation. Denominational leaders sought to eliminate ethnic Japanese churches by not returning property they’d held for them during the war: “Despite having operated independent, self-sufficient churches before the war, white leaders ruled that Nikkei pastors would do so no longer.” A genuine desire for Christian unity met with the realities of the racial hierarchies, resulting in painful dilemmas even for the best-intentioned church leaders. Ultimately, the wartime experience fed a nascent Asian-American theology and a move of mainline Protestants to “expand their definition of unity to include pluralist representations of Christianity as imagined by different sects and ethnic groups.”

One may admire the ministry performed within the camps (and in the postcamp transition) while acknowledging that there was too little protest against the original injustice that precipitated the need for such ministry. That’s a lesson for our time, when political hysteria again has resulted in ill-begotten executive actions. Resistance will be required, and this book documents the consequences that occur when it goes lacking.