What White Christians did to Black Charlotte

Greg Jarrell explores how one congregation in his city took advantage of racist urban renewal policies.

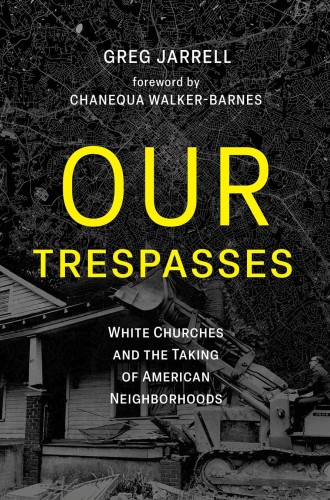

Our Trespasses

White Churches and the Taking of American Neighborhoods

The 20th-century urban renewal movement profoundly impacted most cities across America. Urban renewal gained traction as a federal program to remediate perceived blight by providing funding to demolish urban neighborhoods en masse and spur large-scale redevelopment projects. Due to implicit racism across all levels of government, the program frequently targeted predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Neighborhood advocates and urban planners have long decried urban renewal’s devastating outcomes. In her 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs quoted New York Times reporter Harrison Salisbury to make plain these tragic effects: “When slum clearance enters an area . . . it does not merely rip out slatternly houses. It uproots the people. It tears out the churches. It destroys the local business man. It sends the neighborhood lawyer to new offices downtown and it mangles the tight skein of community friendships and group relationships beyond repair.” In recent years, scholars have published a number of resources recounting the history of racial discrimination in housing and urban planning encapsulated in urban renewal, redlining, and the like. Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law (2017) is one of the most comprehensive and lauded examples.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

After years of ministry and nonprofit leadership in neighborhoods impacted by these policies, I am convinced that urban church leaders must be familiar with this history in order to understand the context of their own ministry. Greg Jarrell’s new book, Our Trespasses, leaves no doubt that the racist legacy of urban renewal programs is also a subject of urgency for church historians and theologians.

Jarrell focuses on the city where he has lived and worked for nearly two decades: Charlotte, North Carolina. The central plot of Our Trespasses documents how one White congregation, First Baptist Church, supported and took advantage of an urban renewal program to secure land in Charlotte’s former Brooklyn neighborhood to build a sprawling church campus in the heart of the city. Jarrell also tracks the parallel story of Abram and Annie North, two formerly enslaved people who lived through Reconstruction and built their home in the Brooklyn neighborhood in the early 20th century. The house was eventually demolished and their descendants relocated; First Baptist’s building now covers the lot where the North home used to be.

These two stories—of the Norths, their neighbors, and their congregation, Friendship Baptist; and of the White members and leaders of First Baptist—unfold and overlap to create a framework for examining racially discriminatory practices that cascaded from the post-Reconstruction era to Jim Crow and redlining and into urban renewal.

Jarrell is an excellent storyteller, which makes this vital history a gripping narrative. Although the ending is essentially known from the outset, he keeps readers turning each page to see what is revealed next in the telling. He balances the weight and detail of his research—which a less capable storyteller may have conveyed with the mustiness of denominational archives and public meeting records—with ethical judgments, curiosity about historical motives, and images of bygone neighborhood haunts.

An example of Jarrell’s ability to use a minor research finding to add narrative substance is his short section on the only remaining artifact from the North house, a framed reprint of Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners. After providing some background on the original artwork, he writes, “Perhaps the Norths saw themselves in it. . . . The painting certainly describes their city, where towers of gold stood in plain sight yet were rendered inaccessible.” Jarrell then notes that Martin Luther King Jr. and a prominent Black art collector at the time also had prints of the painting in their homes.

Perhaps the most important contribution Jarrell makes to our understanding of the urban renewal movement is the array of sources he taps to demonstrate how White congregations and White church leaders shaped and supported the program—at least in Charlotte. He sets this agenda early in the book when he recounts finding a printed report of the city’s redevelopment commission from 1969, which pictures a member of First Baptist as one of the commissioners. “The convergence of political and religious power was plain,” he writes.

Over the course of the book, he uncovers paternalism and condescension toward Black residents by progressive White clergy as they implemented anti-blight programs. He documents how civic leaders used theological language to persuade Black churches that it was God’s work in history to uproot and relocate their houses of worship. And he situates the story of First Baptist within Southern Baptist church growth strategies that overtly took advantage of urban renewal. He writes, “When the white Christians described in this project acted, they acted as Christians, utilizing the resources and content of their faith to make sense of their actions.” The thoroughness with which the author lays this history bare should inspire scholars in other cities to ask anew what role churches, denominational programs, and faith leaders played in advancing the misguided goals of urban renewal.

Some readers may feel that Jarrell is overly preachy as he assesses the historical record and its characters. He is certainly unsparing in his denunciation of racist practices and attitudes where he finds them, past and present. At times he shows righteous anger at what he discovers. But he also rewards readers who stick it out to the end of his story.

Jarrell’s conclusion left me mulling present-day characters in the book that I found both frustrating and relatable, respecting his work as a historian and as an advocate, and pondering what it all means to me as a person of faith and a practitioner in my community. I am exceedingly grateful for how Our Trespasses adds to our understanding of the local impacts of urban renewal through its deep investigation of a particular community, particular churches, and particular people in one southern city. All Christians should be so zealous to fully know and understand the places where we live.