What is poetry in the face of war?

Mosab Abu Toha’s poems are about Gaza. Reading them I saw all people who suffer.

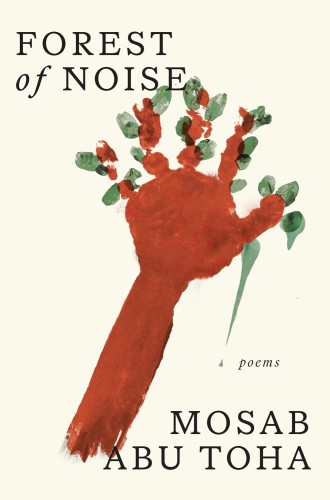

Forest of Noise

Poems

“In the particular is the universal,” said James Joyce. In Forest of Noise, the particular is the Israel-Hamas war and the suffering of the Gazans, as recorded by the award-winning poet Mosab Abu Toha. He told his harrowing story of capture by the Israel Defense Forces and eventual release in the New Yorker, and one of the poems in this collection retells that story. Abu Toha is writing about particulars, and those details appear in the titles of many of his poems: “Gaza Notebook (2021–2022),” “Gazan Family Letters, 2092,” “What a Gazan Should Do during an Israeli Air Strike,” “What a Gazan Mother Does during an Israeli Night Air Strike,” “To My Mother, Staying in an UNRWA School Shelter in the Jabalia Camp.”

When I read these poems, however, I see beyond Gaza. I see Dresden and Ukraine and Poland and Israel. I see it all: Darfur and Rwanda, Sudan, the Uyghurs, and every concentration camp from World War II. Tolstoy once observed that all happy families are alike and each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Yet here in these poems, one can see all global unhappiness in the particulars of the suffering of one people. Here, it seems, all unhappy families are alike. Suffering, of course, is always personal. And it is relentlessly, tragically universal.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The images in Abu Toha’s poems are graphic: “children play soccer / on the beach / they are eight / eight bombs thump the field / four kids killed.” In a prose poem, a young man pulls a suitcase behind him. Inside the case are clothes from his family, killed in an air strike. “The suitcase is their new home and I want to put it in a safe place,” he says. In another poem, a mother gathers her children around her at night:

She hugs each child, still here,

after every bomb and,

if she knows a bomb is about to light up the sky and the room,

she covers her kids’ eyes and

loudly asks

what can you see when your eyes are closed?

Hoping her trembling voice may hide

the bomb’s eradicating sound.

Each of these images is describing an old and starkly familiar story.

In spite of the universal echoes and connections, these are poems of a particular people in a particular conflict. Forest of Noise is, in fact, a documentary. Abu Toha’s poem “1948” begins with the epigraph, “Nakba, the year when Israel was founded after expelling 800,000 Palestinians and destroying 530 villages.” The poem, shorter than a page long, scatters its words and images like bullets and creates in graphic detail the chaos of war and death and choking smoke and pools of blood. In a poem called “After Allen Ginsberg,” echoing that poet’s famous lines, Abu Toha writes, “I saw the best brains of my generation / protruding from their slashed heads.” In another poem, a bone from a girl’s arm is found under the rubble, and the poet asks, “Right or left!” He continues: “It does not matter / as long as we cannot / find the henna / from her neighbors’ wedding /on her skin, / or the ink / from a school pen / on a little index finger.”

In “My Son Throws a Blanket over My Daughter: Gaza, May 2021,” one feels the fear and the surprising compassion of a child in the midst of falling bombs:

My four-year-old daughter, Yaffa,

wearing a pink dress given to her by a friend

hears a bomb explode. She gasps,

covers her mouth with her dress’s ruffles.

Yazzan, her five-and-a-half-year-old brother,

grabs a blanket warmed by his sleepy body,

He lays the blanket on his sister,

You can hide now, he assures her.

Good poetry draws the reader into an experience and often connects it to experiences from the reader’s life. Perhaps surprisingly, what I experienced while reading this collection was a kibbutz just north of the Gazan border. What I observed were children’s playgrounds with slides, swings, jungle gyms—and bunkers every few feet.

What good is poetry as a response to suffering? Is poetry enough? Does the careful and often beautiful language of poetry trivialize the horror of the experience? The epigraph to Forest of Noise is from Audre Lorde: “Poetry is not a luxury.” If not a luxury, what is it? This book suggests that it is a necessity. It tells the truth, and the truth is not always beautiful.

In the final poem in the book, “This Is Not a Poem,” the speaker looks out over “hundreds of stone boxes” containing “all of the body parts / we learned about at school or touched / on our loved ones.” These poems are those stone boxes. His final stanza in this final poem:

This is not a poem.

This is a grave, not

beneath the soil of Homeland,

but above a flat, light white

rag of paper.

Poetry is a merciful presence, vigilant, open-eyed, even if we do not understand the mercy.