The story of Richmond’s “cathedral of the Confederacy”

Christopher Graham’s book focuses on the racism of one Virginia congregation. It will challenge all those who cause harm in the name of virtue.

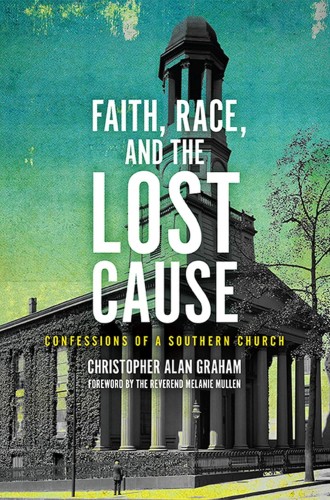

Faith, Race, and the Lost Cause

Confessions of a Southern Church

I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, where the legacy of Robert E. Lee loomed large. Well before I learned Civil War history, I was taught that Lee was a good Christian and a southern gentleman. At family gatherings, one story was told regularly: on his way back from battle, Lee stopped at our family home one night; he was such a gentleman that he insisted on camping out in the backyard so as not to track dirt into the house. With pride, I would retell this story to my friends, concluding with the punch line: “And guess what? Robert E. Lee was my great-great-great grandmother’s cousin!” Twenty-five years later, I am ashamed of my childhood pride in Confederate mythology, but I am not surprised by it. Confederate leaders were shrouded in sainthood at home, in school—our high school mascot was a Confederate soldier—and all the way down Richmond’s storied Monument Avenue.

In Faith, Race, and the Lost Cause, Christopher Alan Graham breaks down the enduring mythology behind Richmond’s Confederate sentimentality as he explores how the people of his parish, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, have understood race and racial relations from a Christian perspective over the past 150 years. As he presents his research on the church that was known as the Cathedral of the Confederacy, Graham makes it abundantly clear that the shape of our storytelling matters as we grapple with legacies of White supremacy.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As he cracks open St. Paul’s history of racism, Graham centers the experiences of White Episcopalians, who have exacerbated racial violence by perpetuating paternalistic tropes and narratives. He writes, “I have averred from describing harm from a Black perspective or going inside Black churches or other refuges to extract that information. . . . I have never felt comfortable, or equipped, in describing or articulating the pain that is neither my own, nor that of the people I study here.” I appreciate Graham’s candor about the limits of his project, and I hope that future research on St. Paul’s will do more to elucidate Black perspectives. Nonetheless, the scope of Graham’s research provides an opportunity for readers to confront plainly St. Paul’s connection to race, slavery, segregation, and discrimination as a wealthy White Christian

institution.

Faith, Race, and the Lost Cause is a must-read for Virginia Episcopalians, but it’s also more than that. Christians in any region and from any denomination will be challenged by Graham’s account of our tendency to cause harm in the name of virtue and charity. Across five chapters, Graham seamlessly weaves his bigger-picture questions into his congregation’s very specific history. As he follows the people of St. Paul’s through the periods of enslavement, emancipation, reconstruction, and civil rights, he invites readers to return to their own histories and to ask: Which stories do we tell? Who is good? How do we remember our ancestors who participated in systems of oppression and injustice? How have White institutions perpetuated “the narrative of faithful slave/waged servant and benevolent master/employer”? How have Christian churches enacted violence against Black people in order to maintain order and control? How do we unravel our lived histories of racism? Where do we go from here?

From Graham, we learn that for generations, St. Paul’s proudly pointed to the pews where Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis sat, and as a result, the entire worship space became a shrine to the Lost Cause. We learn that Monument Avenue’s Robert E. Lee Memorial was erected in 1890 on land donated by a member of St. Paul’s, and the church’s rector at the time gave the dedicatory address. We learn that St. Paul’s responded to a $1.5 million request for reparations in 1969 with a mere $7,500 donation. Perhaps most importantly, we learn that in 2016, St. Paul’s launched its History and Reconciliation Initiative to acknowledge, untangle, and tell this history in full. Indeed, in the work of racial justice, “complacency, not resistance, remained the strongest countervailing force,” Graham elucidates. By demonstrating the ways in which St. Paul’s chose to step out of its own complacency, Graham successfully lifts up the congregation as a model for other churches to do the same. In telling his church’s story, pitfalls and all, Graham invites us to tell our own stories such that the depths of institutional racism might be brought to the surface, one honest conversation at a time.

In telling his congregation's story, pitfalls and all, Graham invites us to tell the stories of our own institutional racism.

I now live in downtown Richmond, just a few blocks from where the Robert E. Lee Monument once stood, and I have watched a bed of bushes grow up quietly in its place. As an Episcopal priest, I continue to field frustrations from Christians who firmly believe that we have failed to preserve Richmond’s history by taking down Confederate monuments. As I hear these complaints, I continue to witness racism run rampant in our city. Paternalism and racism are alive and well in the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, reparations still have not been paid, and I am left wondering: What is the story my church is writing today? We have a long way to go in the work of racial justice and healing here in Virginia, and as Graham so importantly reminds us, simply removing plaques and memorials won’t be enough. The evolving histories we choose to tell will matter greatly.

In the end, Graham’s book is more than a mere analysis of history. It is a moving acknowledgment of sin and the complexities of evil. There is hope even in this, because with every confession of sin comes an opportunity for repentance, reconciliation, and renewal of life.