The stickers and boomers of Idaho’s Treasure Valley

Grace Olmstead has written a reverent ode to those who stick around.

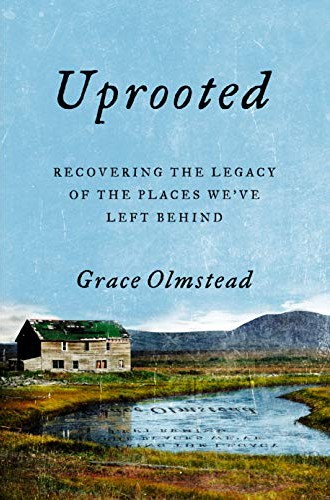

Uprooted

Recovering the Legacy of the Places We’ve Left Behind

On the way to church each week I pass the Great American Neighborhood. It’s one of at least five developments in my area living under that registered trademark. The development company says it builds “places as special as the people who live in them.” It’s a fascinating notion, customizing a place to folks who are not yet there, and one so pretentious that only late capitalism could have dreamed it up. We want everything—even the cornfield to which we have not yet moved—to speak our name.

At the center of journalist Grace Olmstead’s new book is the kind of town this development (with its summer movie nights, “shared spaces to be enjoyed with neighbors and friends,” and “sense of timelessness”) feigns to be. Uprooted is an inquiry into a farming community and the lives of those the novelist Wallace Stegner calls “stickers,” or people who commit to a place, as well as their antithesis, “boomers,” those who move to a place until it suits them to leave. Olmstead describes Stegner’s archetypes thusly: “Stickers are those who settle down and invest. Boomers come to extract value from a place and then leave.”

Uprooted serves as a reverent ode to stickers—in particular, those in Emmett, Idaho, a farm town where Olmstead’s family lived for generations and which serves as the beating heart of her project. It’s a place of cherry orchards and dairy farms, fields of sugar beets and alfalfa—and, increasingly, a place spun dry by the centrifugal forces of modernity. Like Wendell Berry writes of Port William, the fictional town at the center of much of his fiction, Emmett is “the sort of place that pretentious or ambitious people were inclined to leave.”