The historical roots of interfaith dialogue

Tal Howard offers a carefully researched history, from the Mughal Empire to Nostra aetate and beyond.

Several questions enliven Thomas Albert Howard’s fast-paced history of interreligious dialogue. Where did the interfaith movement come from? Where is it going? “Rarely in history is something entirely unprecedented,” he writes, so how does interfaith dialogue go from “virtually nonexistent, or rare and episodic at best, in the premodern and much of the modern era . . . to becoming a widely embraced ideal in the twentieth century”?

A professor of humanities and history who holds a chair in Christian ethics at Valparaiso University, Howard tells the story of today’s expanding interfaith engagement by focusing on four pivotal moments. He begins in the 16th-century Mughal Empire in India, where the Muslim emperor Akbar hosted intellectual salons with Jews and Christians. He ends in Rome with the promulgation of Nostra aetate by the Catholic Church in 1965. In between, Howard introduces a chapter on the first Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago in 1893 and another devoted to the less well-known 1924 London Conference on Some Living Religions within the Empire, which introduced Eastern religions and Islam to the British public.

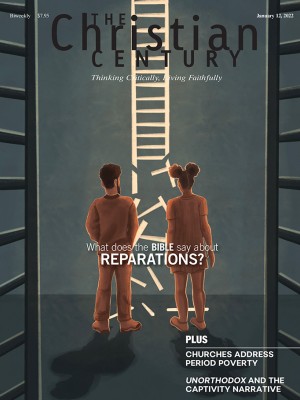

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Each of the chapters is expansive in its approach to the main event, including information about the key players, what predisposed their thinking, and how the events influenced religious engagements that followed. Howard notes that from earliest times, devout adherents struggled to understand and accept religious diversity. It would be a stretch, he writes, “to characterize early medieval interactions . . . as dialogue in the modern sense, but various polemical exchanges bear witness to efforts to make sense of the alterity of rival faiths and to explain one’s own.”

In the largely Christian West, interfaith engagement was not inevitable, according to Howard. Christian theological exclusivism and supersessionism argued against meeting with other religions except to proselytize. That kept devout Catholics and evangelical Protestants from participating in the first Parliament of the World’s Religions and nearly derailed the efforts of the Second Vatican Council to embrace Nostra aetate.

Howard offers an incisive review of the machinations over the four years and four different official meetings of Vatican II. For those not familiar with the history, this chapter provides an excellent and exciting overview of the inner workings, the diverse influences, and the resulting substantial opposition to the document, which some have called a 180-degree turn in the Catholic approach to other faith communities. “A document originally intended as a theological statement on the Jews and a condemnation of anti-Semitism survived but underwent a metamorphosis to include many ‘major world religions,’” Howard writes. (Full disclosure: Howard did archival research at the American Jewish Committee, where I work, and he writes about AJC’s efforts to influence the outcome of the council.)

Howard does not limit this chapter to the 1965 promulgation of Nostra aetate. He analyzes several official documents that preceded it and several others issued after it. These documents—in some, but not all cases—help to explain and amplify Nostra aetate’s message. These pages will help non-Catholics understand the importance of documents in the Catholic Church and appreciate the ongoing challenges to interfaith engagement emanating from some elements within that church.

Howard’s book is methodically researched, with three pages of sources and 76 pages of footnotes, including a footnote noting that the term interreligious was first used in 1847 and the word interfaith was first used in 1932. Howard uses the terms interchangeably, as do many scholars and practitioners.

“Religion is a vast and often bewildering field,” Howard notes, quoting from a 55-year-old AJC guide to interreligious dialogue. He reviews common criticisms of interreligious engagement, including that much of the global interfaith dialogue is Western-centric and oriented toward elites. Another criticism is the difficulty in identifying who can authentically and authoritatively speak for non-Western traditions. Another is that much of the existing dialogue is bland and favors nonbinding and ineffective statements on peace and the benefits of coexistence, which have little impact on the lives and faith practices of most people.

Howard ends with his belief that interfaith engagement is evolving and, despite the criticisms, continues to be worthwhile as we try to make sense of our “globalized, pluralistic, postcolonial, cosmopolitan, perduringly religious world.” For those who are new to the field or are interested in looking at where we’ve been and how we came to be here, this book is a very good place to start.