Finding ourselves in a Nigerian war novel

Chigozie Obioma offers a narrative that transcends bullets and politics.

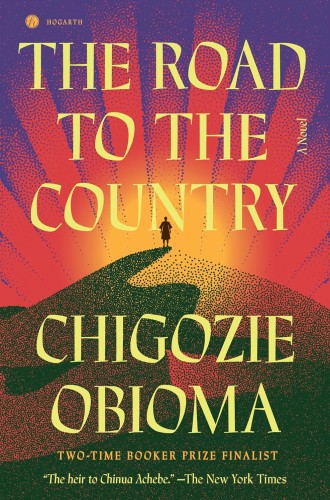

The Road to the Country

Chigozie Obioma loves to destabilize the way his readers experience the novel as a genre. The Nigerian writer is arguably most daring on this front in his latest novel, in which he delves farther back in time than in The Fishermen (2015) and An Orchestra of Minorities (2019). The Road to the Country is set in Nigeria in the 1960s, the era of the Biafran War, but it is not simply a historical war novel. Though it contains conventions of the genre—characters full of masculine bravado, long passages illustrating the devastation of post-traumatic stress disorder—Obioma draws as well from magic realist impulses, creating a story of togetherness amid the hypothetical.

The Biafran War (1967–1970) was Nigeria’s big “what if?” civil war, in which the oil-rich Biafra region broke from the greater Nigerian nation in response to repeated oppression of the Igbo people, Obioma’s own ethnic group. It is a war that figures heavily in Igbo identity—with echoes in the writing of Chinua Achebe and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, among many others—and a source of both pride and sorrow.

In The Road to the Country, the main character, Kunle, journeys into Biafra at the start of the war in order to find and bring back his younger brother, Tunde. Added to the wartime urgency is a story of trauma told at the beginning of the novel: Kunle feels responsible for an accident when they were younger that left Tunde wheelchair bound. “The days acquired a palpable darkness” for Kunle after the accident, says the narrator, “and together they became the night of his life.” And thus, with a combination of guilt, grief, and brotherly love, an incredible engine of a plot is born.