The selfie and Sojourner Truth

Little did tennis star Andre Agassi know that he was speaking prophetically when he declared in 1990s Canon camera commercials that “image is everything.” The truth of his marketing statement seems everywhere today. Pope Francis was not only Time’s “person of the year.” He was also Esquire’s “best dressed man of 2013.” The new pope is what he says, does and wears.

2013 was also the year of the “selfie.” Named word of the year by the Oxford English Dictionary, the selfie begins with a person holding a camera (or camera phone) at arm’s length, pointing it toward oneself, and taking a picture. The self picture is then shared through Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. It would be weird if I had dozens of photographs of myself in my kitchen, living room, office, basement, bathroom and garage. But on my computer or phone, it is acceptable. Social media sites have become halls of mirrors and museums of the self where we invite others to gaze upon us. When I look at the screen, I stare back at me.

“Image is everything” in Christian book culture, too. When Joel Osteen publishes bestsellers, it is impossible to walk through an airport without dozens (if not hundreds) of slick-haired Joels smiling at us. Osteen did not invent this tradition, and we cannot pin it to his prosperity gospel. Billy Graham’s face was front and center on the cover of Peace with God in 1963. Reinhold Niebuhr was not on the first edition of Moral Man and Immoral Society from 1932, but subsequent editions placed his face on the cover.

The easy Christian and psychological response is to decry our image-obsessed, narcissistic culture. “The Lord does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart,” we may sigh with the prophet Samuel as we wag our heads or fingers.

There may be other ways to think about our focus on faces and our obsession with images. I believe that God loves our bodies—just not our body worship. Perhaps we can celebrate both what God made (our bodies) and what God made us for (our hearts and actions).

Some answers may come from one of the first Americans to ingeniously use images and theologize them brilliantly: Sojourner Truth.

Growing up in New York as a slave (or rather, as a “person who was legally owned by another person,” which is how I refer to people in this condition in my classrooms so that I affirm their God-made personhood), she was first known as Isabella Baumfree. She gained her freedom in the 1820s and then went on a search for her place in the kingdoms of humans and of God. Eventually, she named herself Sojourner Truth.

Sojourner Truth became a powerful force in both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements. She defied any white American who saw her as less-than-human because of her race. She defied any male American who saw her as less-than-human because of her gender. And she made sure with her name that no person could refer to her as less than God’s child. “Sojourner Truth” not only signaled her identity as a searcher for God but also forced others to address her as one. To talk about or to Sojourner Truth, one had to speak “truth.”

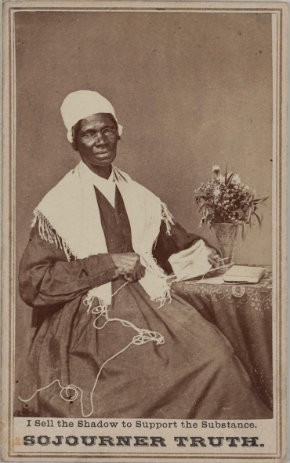

Her name was one part of her new identity. Photographs of her were another. Sojourner Truth distributed and sold images of herself. The caption at the bottom explained her motive and meaning: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

We should pause and sit under Sojourner Truth’s tutelage. Her one sentence may hold the key to make unselfish our culture of self(ie)ishness. She knew the image was a shadow, and shadows are often difficult to define. Her image did not move, it did not breathe, it did not bleed, it did not hug and it did not love. In a world that wanted to limit her in so many ways, she refused to be limited by her photograph.

But the shadow was useful, and not as a mirror for narcissism. Her photographs, in part financially, supported the substance: her body, her words and her actions.

Sojourner Truth made it clear what mattered. Her (and our) substance is not in pictures of our bodies, but in our bodies themselves—and what we do with them.

I wonder if our age of and rage for selfies speaks to our forgetfulness of who we are. In a book dedicated to action, the biblical writer of James likens those who hear God’s words and do not follow them to be “like those who look at themselves in a mirror; for they look at themselves and, on going away, immediately forget what they were like.”

What do we look like beyond the selfies and the self image? Jesus may answer this when he explains that those who act in concert with God’s will are Jesus’ sisters, brothers and mother. As we see in God a parent, perhaps God genuinely sees us as family members. When I remember that, I feel less interested in displaying myself to the world and more interested in what I can do in God’s world filled with God's children.

Our weekly feature Then and Now harnesses the expertise of American religious historians who care about the cities of God and the cities of humans. It's edited by Edward J. Blum.