Another Jesus clone?

Nearly every comic about Jesus attempts to clone him. As a character, Jesus has been reproduced endlessly and shuffled about, pasted into all sorts of locales and warped beyond recognition. The graphic form allows readers and artists to experience his significance in situations far removed from earlier forms. Some comics reconstruct first-century Palestine, others create analogs with the present day. Mark Millar’s unfinished series American Jesus , for example, features a middle-American character who’s considering whether he might be Jesus.

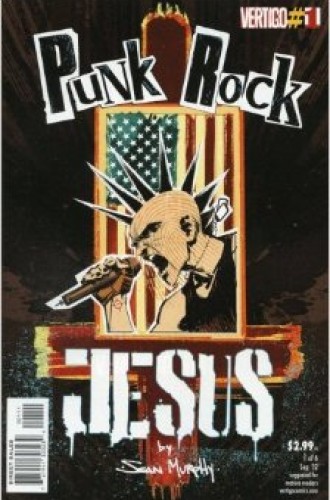

Sean Murphy’s Punk Rock Jesus features a more explicit reproduction: Chris, a putative Jesus clone. Chris shares Jesus’ genetic makeup—using material extracted from the Shroud of Turin —but he is not Jesus. He is not the return of Jesus, as some characters in the book believe. In fact, he revolts against his strange origins and embraces an anti-religious mission as a singer in a punk band. The duplicate turns on the original.

Punk Rock Jesus is a categorical leap beyond other Jesus comics, because it calls attention to their hollow attempts to replicate Jesus. Chris lives his life as the star of J2, a 24-hour reality show. After the show’s demise, its creator, Rick Slate, testifies before a congressional investigative committee—where he abbreviates Peter’s Pentecost sermon. Was this man the Christ? Yes, says Slate, detailing how the comic’s events are in fact what happened to Jesus in the Gospels. Chris is a copy of Jesus in the ways that matter.

If Slate is Peter, Gwen, a teenage virgin selected by the reality show’s corporate sponsor to bear an artificially inseminated egg to term, is Mary—and security officer and former IRA member Thomas McKael is Thomas. The comic’s characters call attention to these parallels, even mocking the narrative as it progresses. In one scene, McKael tells his assistant, Tim, that he has pledged not to kill for Jesus’ sake. Tim replies that in bad comic-book stories, these sorts of oaths are often broken.

The story at many times threatens to prove Tim right. It occurs in a world where a group called the New American Christians sees blasphemy in Chris and responds by violently attacking the J2 project. And McKael desperately wishes Chris to be Christ for his personal salvation from his religiously motivated violence.

As for J2, it calls attention to itself as a repetition of Jesus without apology or deception. But it also injects important differences. Because this is America, Chris has to be a blue-eyed white man. When he attends his high school prom, he can’t take the girl he asked—he has to go with the cheerleader that J2 bribed. Slate says this isn’t his or the project’s fault: this is the Christ that contemporary culture demands.

The culture also demands violence, which permeates the book. We see it in McKael’s backstory and in the New American Christians; later, Middle Eastern terrorists enter the scene as well. From beginning to end, religiously inflected warfare plays a major role in the forces that surround young Chris.

And, like his genetic forebear, he rejects them. Only Chris’s rejection means rejecting the J2 project, the United States and religious belief all together. The violence Chris then wields in the form of his punk band targets the excess of religion, and this horrifies Christians and secularists alike—provoking readers to wonder with the other characters who Chris really is.

He spits out his own answer: I am not Jesus at all. This response calls attention to Chris as Chris, not as a duplicate, but also notes the legacy he bears: he is supposed to be the Christ but is not.

Comics can offer a version of what the Second Council of Nicaea called the “written image” embodied by icons. Murphy’s remarkable talent resides in his depiction of human faces and bodies: characters vividly reveal fear, protest, disregard. A face discloses and obscures more than words alone can. Comics draw our attention to the disjunction and connection between word and image, between face and action, body and speech. There is no interior person, only faces, words and bodies.

In the end, says a genetic scientist character name Rachel, all we have is this world, a world that consists of these faces and bodies. Into this world comes the cloned Jesus, who demands justice for those bodies. In whatever form the gospel is inscribed, this Jesus demands us to call attention to the body, torn by violence. In Punk Rock Jesus, the cross, the crucifix alone is our theology.