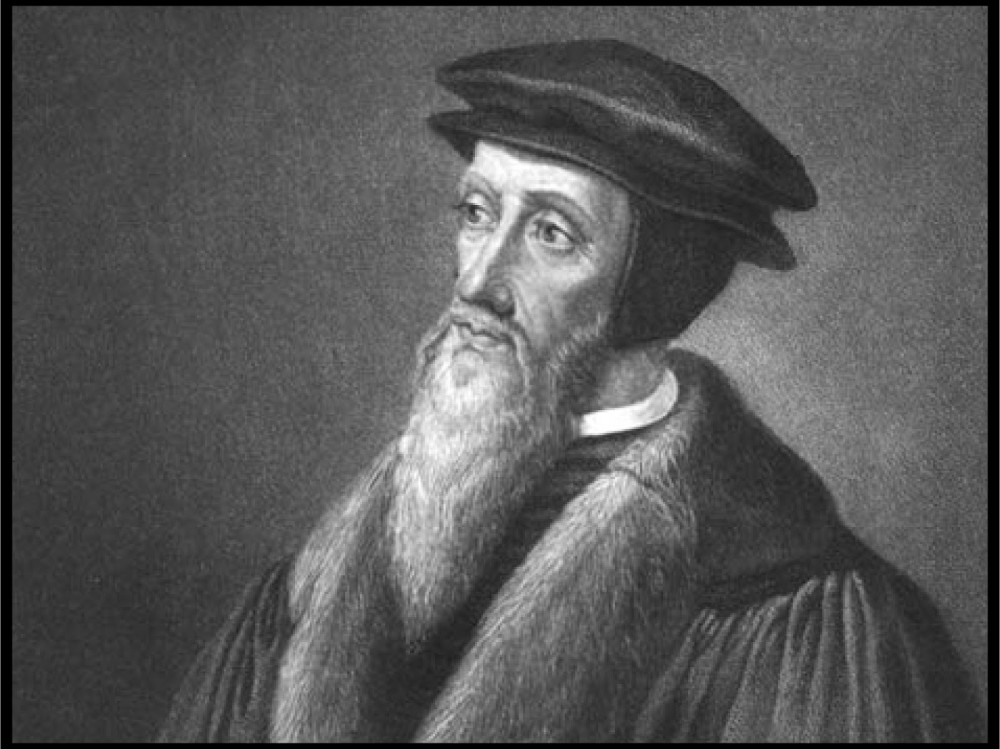

John Calvin: Source for political resistance?

Calvin's political theology contains radical implications relevant for resistance today. Yet, Calvin also carries reactionary, anti-democratic impulses that make him a complicated figure.

John Calvin does not always receive the best press. He is often portrayed as an archconservative and an ideological father of capitalism. Most recently, the topic of Calvinism returned to public attention when Betsy DeVos was nominated Secretary of Education by Donald Trump. As a Politico report in January 2017 demonstrated, journalists were quick to associate DeVos’ political conservatism with the Calvinism of her Christian Reformed Church denomination. This association is also situated within a larger move to reduce Calvin to Max Weber’s thesis in The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism which showed Calvinism’s contribution to capitalist ethics.

In this view, Calvin is not only associated with DeVos’ educational policies (which stress privatization) but also with Trump’s persona of being a successful businessman. Yet, notwithstanding the historical links between Calvinism and the rise of capitalism, what if there is actually more to Calvin’s thought than these one-dimensional associations? What if John Calvin’s thought is also a potential source for radical political resistance?