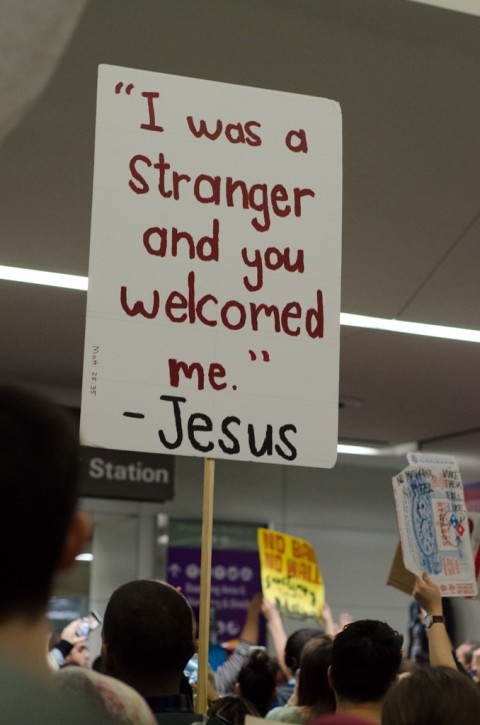

Loving and protecting immigrants is a biblical command

The Hebrew Bible's instruction to love the neighbor appears only once. “Love the stranger” appears more than 35 times.

Language is always more than a communication tool. It also shapes culture and affects relationships. When U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) recently issued a new mission statement eliminating wording that had celebrated “America’s promise as a nation of immigrants,” the shift marked a sharp political turn inward. Gone were the words of generous welcome in the previous statement like providing, granting, promoting, and understanding. In their place came verbs of demarcation and fortification like safeguarding, protecting [Americans], and securing [the homeland]. The message of the changed language was unmistakable: it’s time to focus more on keeping immigrants out than on allowing them in.

This development isn’t entirely surprising. For generations, many Americans have been suspicious of newcomers, often disparaging strangers and demonizing immigrants. The term alien is more popular among xenophobes than immigrant. New strains of nationalism consider the country’s very identity to be under threat from a breakup of shared cultural, racial, religious, and linguistic commonalities. Fear of the other produces language tinged with hostility.

So long as we view the immigrant more as stranger than as neighbor, we’re bound to behave less hospitably. It might help if we could recognize that no person has “stranger” as his or her own self-definition or core identity. Strangeness isn’t a personal characteristic of the people we don’t know. Others merely appear strange to us from our vantage point. When we refer to someone as a “disabled person” instead of a “person living with disabilities,” we impose a similar external opinion on that individual’s primary identity. Our own vantage point ends up diminishing the richness of the other.