On Herrens veje, church leaders have to justify their existence

The Danish TV series portrays the choppy waters of European Christianity.

The nation of Denmark usually rates high in global measurements of secularism and the rapid contraction of organized religion. How strange, then, to find that country producing an appealing and well-made piece of popular culture based on the church and the dilemmas of clerical life. American viewers will find it eye-opening for the picture it offers of Protestant Christianity in contemporary Europe.

I’m speaking of the Danish television series Herrens veje (literally “The Ways of the Lord,” but titled in English Ride upon the Storm). This 2017–2018 production was enormously popular in its home country (it is available through Netflix). The central figure is Johannes Krogh, a dean in the country’s established Lutheran church, together with his two sons, August and Christian.

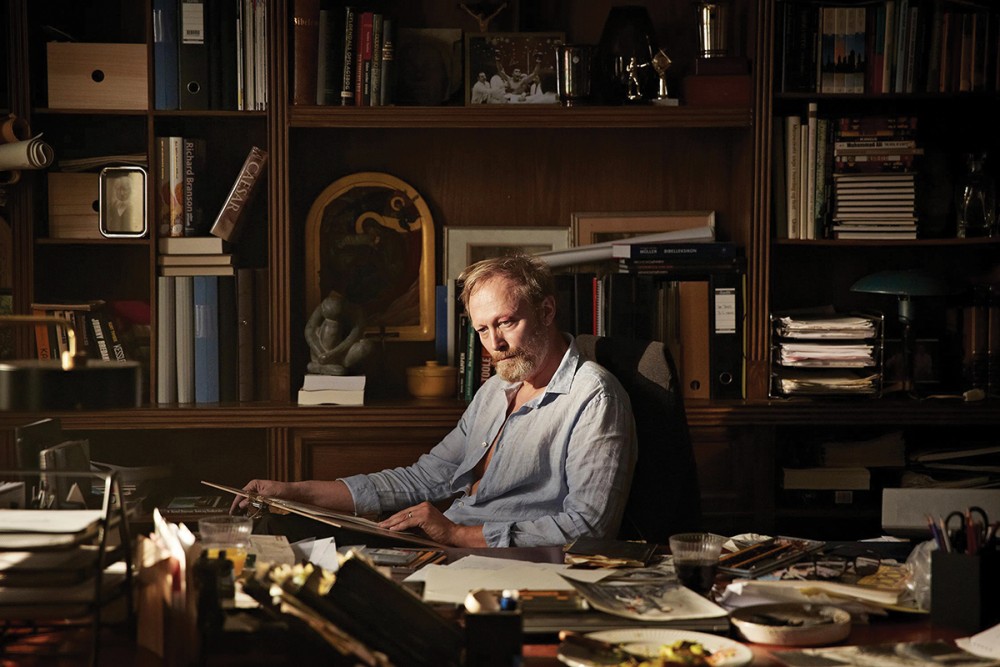

The series certainly contains elements of soap opera. Johannes (brilliantly played by Lars Mikkelsen) is a tempestuous figure, authoritarian and over-ambitious, with a weakness for adultery. Other family members have their own dark secrets. But the show also gives a provocative portrait of the larger church and the issues it faces. So immediate is its relevance that many Danish churches have formed groups to discuss the themes and ethical debates arising from each episode.