After getting out the vote, Black church leaders look ahead

On the last Sunday of October, Karl Anderson helped arrange a Souls to the Polls event on a blocked-off street in downtown Gainesville, Florida, to encourage people to vote early.

The bipartisan gathering included candidate speeches, free hot dogs and hamburgers courtesy of the NAACP, and live gospel music. Between speeches and music, clergy prayed. Some participants, wary of the coronavirus, watched from a distance in the “park and praise section.”

But the location was the main attraction.

“It was on the back street of the Alachua County Supervisor of Elections office,” said Anderson, a Church of God in Christ pastor who also runs a marketing business in Gainesville. “All they had to do was walk over there. We had a total of 423 voters that day.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Black voters were already ramped up to participate in the 2020 election due to warnings about voter suppression, as well as the recent killings of unarmed Black people. But faith leaders said that unprecedented coordination of their get-out-the-vote efforts were also key to higher rates of participation and greater enthusiasm among voters.

African Methodist Episcopal Church officials contacted more than a million people, more than doubling their 2016 reach, said Jacquelyn Dupont-Walker, the AME’s national social justice commission director. Tens of thousands of people heard from them on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube in addition to traditional methods such as phone banks. Video messages sent by denominational leaders went viral.

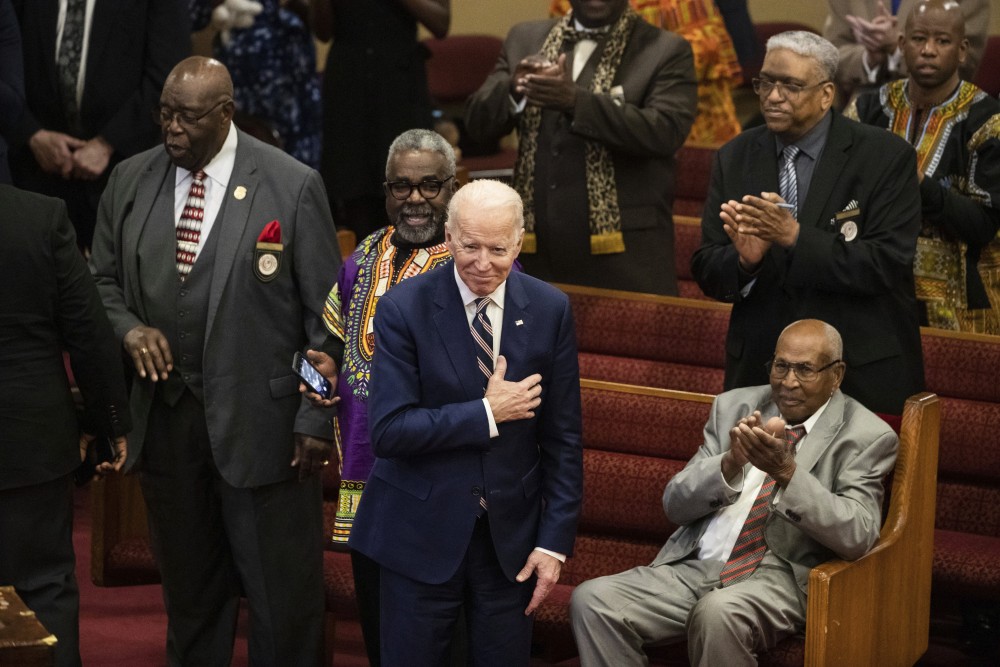

Mike McBride, a Pentecostal minister in California, worked with faith-based campaigns including Live Free, a campaign of the multifaith and nonpartisan Faith in Action, and the Black Church PAC, which backed Joe Biden.

McBride said church groups used “every tool we had in our belt,” from a 14-city southern bus tour to a Black Church Rocks virtual gospel concert. Field teams knocked on tens of thousands of doors in Georgia and Florida.

The Conference of National Black Churches partnered with Al Sharpton and his National Action Network for the Black Church 75 initiative, which aimed to register at least 75 percent of the membership of 1,000 churches affiliated with the group.

They exceeded their goal, registering 84 percent of member churches in eight states, with about a third of those in Georgia, where Biden won by a small margin.

Race played a large role in many of the contests that determined the election, especially in the wake of this summer’s marches and the Black Lives Matter movement’s prominence in the news. Black voters, who tended to look favorably on the BLM movement, voted in huge majorities for Biden, while Trump voters took an opposite view on those issues, as Robert P. Jones of the Public Religion Research Institute pointed out.

That suggests a split between White and Black Christians as well. “While the exit polls don’t break out African Americans by religion, nine in ten African Americans supported Biden, and eight in ten African Americans identify as Christian,” said Jones, who noted that the “overwhelming support” for Biden is consistent with PRRI research about support for Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Keon Gerow, a Black pastor in Philadelphia, served as a poll chaplain with the Lawyers and Collars program, which supplied legal experts and clergy as observers and peacekeepers at voting locations in nine states. He was impressed with the sheer number of voters as well as the enthusiasm of mostly Black millennials as they left polling places.

“I was shocked to see the number of individuals between the ages of 21 and 40 who were coming out to the polls—with their friends as well—who were very engaged and extremely informed as to why they were voting and some of the issues that mattered most to them,” he said.

“One of the biggest issues was police brutality and racial injustice in America right now,” he added. Gerow said many Black voters he spoke with “attributed their understanding of those salient issues to the role of the Black church,” including via social media posts, sermon mentions, and church announcements.

In Georgia, Christy Davis Jackson, state supervisor of the AME’s Women’s Missionary Society, said the shooting death of Ahmaud Arbery galvanized people of faith to highlight the reelection bid of Brunswick Judicial Circuit district attorney Jackie Johnson, whose handling of the case was called into question.

“They were so passionate that social justice needed to be the centerpiece in that campaign,” Jackson said of the volunteers. Johnson was unseated by Keith Higgins, an independent candidate.

For many, the hero of the 2020 vote is Stacey Abrams, whose loss in the 2018 gubernatorial election in Georgia spurred her to found Fair Fight, a voter protection movement. Along with leaders such as Traci Blackmon and Leah Daughtry, founding members of the Black Church PAC, Abrams inspired many people to new levels of activism.

The Christian activists acknowledge that there were limits to what churches could accomplish. “I think we have to be able to do a better job of reaching the broader community of the African American community, not just church people,” said W. Franklyn Richardson, chairman of the National Action Network and the Conference of National Black Churches.

Another goal is to influence not just the vote but the new lawmakers they helped elect.

“Bad governance is de facto voter suppression,” said McBride. “We’re going to have to hold everybody accountable, including Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.”

Anderson, the Florida pastor who staged the Souls to the Polls event, said, “The Bible says that the government should be upon his shoulders, and we are those shoulders,” referring to the book of Isaiah.

“We represent the body of Christ, and so we can’t just sit idle and allow things to happen and depend solely on the government. We have to have influence. We have to have leadership. We have to have a voice.” —Religion News Service

This story was supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.