Fresh from his baptism, still waterlogged from the Jordan, Jesus is thrust into the wilderness for a time of preparation and testing. Mark doesn’t give us many details—there is no biblical repartee between Jesus and Satan here as in Matthew and Luke—but what we do get is vivid. Angels tend to Jesus. And he is “with the wild beasts.”

It’s a disorienting narrative, toggling between two distinctly contrasting moods. Immediately prior to these verses, we’re introduced to John and his bracing manner. His demeanor and words are meant to challenge, not coddle. So the baptism, we must imagine, is no dainty sprinkling of water but an unceremonious dunking. Jesus is baptized by his prophetic cousin, standing waist deep in the river, John’s camel’s-hair robe hanging heavy on his shoulders, and the ritual is punctuated by the heavens ripping apart.

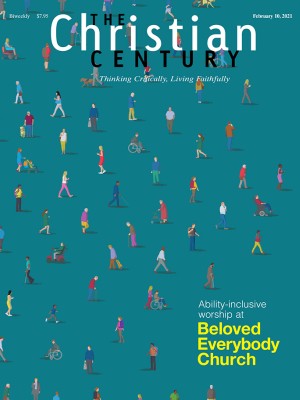

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But then . . . the Spirit descends like a dove. Through that curtain of sky, an unassuming bird of the air flutters down. The juxtaposition couldn’t be clearer between camel’s hair and downy feather, between the rent heavens and a gentle cooing. Then comes the voice, uttering words of comfort: “With you I am well pleased.” As in Luke (but unlike in Matthew), this affirmation is for Jesus’ ears alone.

Then comes Mark’s signature word, immediately, and the tone shifts again. That same Spirit who just alighted on Jesus now beats its wings and nips at Jesus’ head, driving him into the wilderness as if Hitchcock had choreographed the scene. Jesus will remain there for 40 days, tempted by Satan. Brian Blount expresses the dynamic well in Preaching Mark in Two Voices: “Want to know what happens when you get too close to God, when you get touched by the power of God’s Spirit? You don’t sit still and enjoy the view, you don’t lay down and take a nap, you don’t bask in the glory of what great thing has just happened to you. You go immediately to wild work. To work for God is to be thrown directly into the path of those who would oppose God.”

But again there is a contrast. Jesus is not alone in this wild work. He’s being tended. The word connotes shepherds looking after a flock, or a parent nursing a child through illness. In this case, angels keep the vigil—but not just angels.

A good friend who works in campus ministry is one of my go-to phone calls when I face a great challenge or crisis, and I am hers. Often we close the conversation by saying, “May the wild beasts minister to you.” We know full well that is misreading the text—after all, the angels do the ministering, not the animals. The wild beasts are simply “with” Jesus. Yet I believe it’s a faithful misreading. Angels have a soft, comforting image in our culture but not always in scripture. Sometimes a gentle, well-coiffed angel doesn’t cut it. There are occasions when we need the heavy artillery, spiritually speaking. When we’re in the fight of our lives, we need courage and strength. We need a sidewinder, sent from God, on our side. Or a scorpion. Maybe that dove-like Spirit at the baptism transformed into a turkey vulture for the testing.

What does it mean that the wild beasts were with Jesus? Perhaps their sheer wildness was an inspiration to him. Their lack of tameness gave him the strength he needed to go mano a mano with the Adversary, who was relentless in his struggle to divert, distract, or seduce Jesus away from his mission. Or perhaps the wild beasts were tame in comparison with Jesus, the Son of God who confounds our expectations, who is always surprising us.

My father was an intrepid motorcyclist who traveled all over the country and encountered all sorts of weather, mechanical breakdowns, and the occasional unsavory character. He once said he was never so frightened as he was in the middle of the wilderness of Death Valley. While traveling with my teenage brother, they made a wrong turn and found themselves on a deserted road that soon became a gravel road. They gradually realized that they were dreadfully low on gas, with no cell phones, rest stop, or other motorists anywhere in sight—and no idea where they were. My father was reassuring at the time, but afterward, he admitted he was scared. And yet he couldn’t help but feel a sense of awe at the sheer power of the desert landscape. It’s a place both severe and oddly beautiful—a place that cannot be conquered or cultivated, that doesn’t care about us, that can make quick work of us.

As the Godly Play curriculum puts it, “the desert is a dangerous place. . . . No one goes into the desert unless they have to.” That’s the kind of place where Jesus was tested.

Once Jesus returns to begin his public ministry, he proclaims the time fulfilled: “The kingdom of God has come near.” In what tone do we hear these words? Is this the comforting voice of the baptismal Spirit or the harsh edginess of John and the wilderness beasts? Perhaps, like the complexity of the life of faith, it is both at once.