March 5, Lent 2A (John 3:1-17)

Triumphalist uses of John 3:16 contradict the verse's historical context.

Nicodemus is no villain. Jesus’ learned conversation with this religious leader showed his early followers that he could hold his own with the best thinkers of his community on the topic of life after death, a pressing issue in a time of Jewish martyrdom.

Contemporary Jews often see the first-century Pharisees as their direct religious ancestors. Derogatory talk about the Pharisees may quickly devolve into antisemitic fodder today, and we must take seriously the rise in violent acts against Jewish communities around the world. John’s terms “Pharisee” and “the Jews” have been a driving force behind antisemitism. It’s not the fault of the Gospel’s writer so much as of those who have misunderstood its historical context. While far too much damage has been done to repair this in a sermon, the diligent work of dismantling antisemitism is part of our ongoing work as Christians.

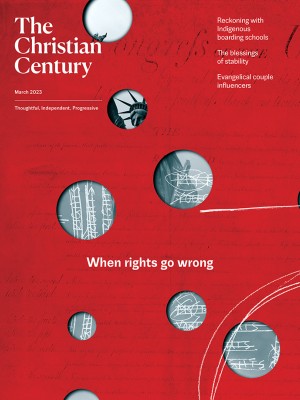

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Thankfully we can turn to the numerous resources available from Jewish New Testament scholars: anything by Amy-Jill Levine, including the Jewish Annotated New Testament (now in its second edition), which she coedited with Marc Zvi Brettler, joined by scores of other Jewish New Testament scholars. Such resources can help us teach and preach the New Testament in a way that avoids antisemitic pitfalls, preventing us from fostering misguided hate.The point of this passage is the salvation of the world. Though verse 17 states this clearly, verse 16 has ironically held a status as the most favored Christian triumphalist proof text, with emphasis on “everyone who believes in him” as the focal point for attaining eternal life. That exclusivist usage not only contradicts the salvific tone of the next verse, it misleads us about the historical setting of the earliest audiences. While this passage about an afterlife of salvation was being written, the Roman Empire was pushing Jesus followers underground and following up with persecution. Triumphalist uses of John 3:16 miss that context to our detriment.

While Martin Luther called verse 16 the “gospel in miniature,” the words of the wider passage beckon us into their abstract, complex, mystical symbolism. They do not distill into simplistic dogma: kingdom of God, above, womb, born, water, spirit/breath, flesh, earthly, heavenly. They point to creation and to the first chapter of John, which similarly teems with imagery about “the beginning.” Moses and the serpent (Num. 21:8–9) provides a scriptural story to further unlock the author’s understanding about Jesus. There is something paradoxical, awesome, and utterly salvific in Moses holding up the bronze serpent to save those who have been bitten by angry snakes, viewed as horrific messengers of divine punishment. By analogy, looking at the lifted-up Jesus on the cross should inspire a similarly paradoxical, awesome, and utterly salvific experience.

The conversation with Nicodemus is set before Jesus is crucified, but it was written about 50 years afterward. The idea that Christ crucified was salvific seems obvious to most Christians today, but we do not live with the threat of crucifixion. The earliest followers of Jesus were still trying to imagine how a leader who was brutally executed by the empire could be their Messiah. The Messiah was not supposed to be crucified but was expected to officiate a peaceful rule from Zion. The idea of salvation through belief in a crucified leader was a scandalous theological innovation.

The author of John’s Gospel pulls out all the stops to convince early readers that it could work: through philosophical reasoning, poetic imagery, and analogous use of the audience’s own holy stories. The plural “you” (see the translators’ footnotes in the NRSV) reminds us that Jesus’ audience goes well beyond Nicodemus—to a diverse ancient audience and on to us. The language invites us right into this scene with the persecuted early followers of Jesus.

Christians in America enjoy legal protections, majority status, and global power. We are more analogous to the Romans than to the early followers of Jesus. Coming back to the history of Christian antisemitism, we have wielded our power in that way for most of our history. This point is too often lost when we think of ourselves as emulating the Jesus communities of the first century. We have no idea. “Happy Holidays” on a paper coffee cup provides no point of comparison with the Roman subjugation of early Jesus followers. How can we grapple with the power we hold in our contemporary world, in order to avoid playing the part of the ancient Roman Empire?