Whiteness rooted in place

“All of our efforts at changing the social fabric of this country must begin with changing the geographic fabric.”

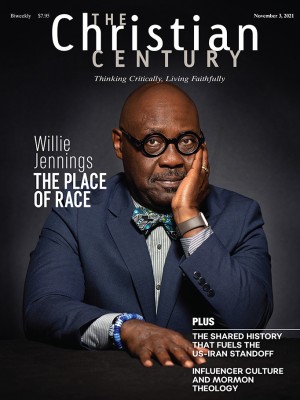

Willie Jennings teaches systematic theology and Africana studies at Yale Divinity School. His most recent book is After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging.

Let’s start with your understanding of this thing we call race. What is it?

Race is a distorted way of seeing the world within Christian thought. We might want to say that race is a distorted view of creation, a distorted view of the order of the body and of the relationship between the body and land, and a distorted view of the relations that should exist because of those views of body and land.

There was a time on this planet when no one would have imagined themselves encased in something called race. That’s not to say that there were not always elements that later on would coalesce into the racial imagination—people identifying others differently from themselves or springing off things like phenotype and bodily description. But race is not part of the created order. It is a particular historical emergence of a way of perceiving oneself and the world. While inexplicable in its forming, it became self-explanatory while also explaining the world.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

You say that race was formed within Christian thought. What does it have to do with theology?

The modern vision of race would not be possible without Christianity. This is a complicated statement, but I want people to think about this.

Inside the modern racial consciousness there is a Christian architecture, and also there is a racial architecture inside of modern Christian existence. There are three things we have to put on the table in order to understand how deeply race is tied to Christianity. The first brings us back to the very heart of Christianity, the very heart of the story that makes Christian life intelligible.

That story is simply this: through a particular people called Israel, God brought the redemption of the world. That people’s story becomes the means through which we understand who God is and what God has done. Christianity is inside Israel’s story. At a certain point in time, the people who began to believe that story were more than just the people of Israel, more than just Jews. And at some point in time, those new believers, the gentiles, got tired of being told that they were strangers brought into someone else’s story—that this was not their story. They began—very early and very clearly—to push Israel out from its own story. They narrated their Christian existence as if Israel were not crucial to it.

The fact that Christians came to identify themselves as the chosen people is already a profound distortion of the story. But this is where they are when we come to the colonial moment. They believe that they are at the very center of what God wants to do in the world. This belief is in everything they do and say: the way they read the Bible, the way they form their theology, the way they teach, the way they carry out their Christian lives.

As they begin to realize their power, they also realize the power to shape the perceptions of themselves and others. That is, they begin to understand that not only do they have the power to transform the landscape and the built environment, but they also have the power to force people into a different perception of the world and of themselves.

This is what we came to call European: the power to transform the land and the perception of the people. A racial vision started to emerge. It floated around in many places with many differences in body type, skin color, and so forth. It didn’t come out of nowhere. But now, inside this matrix, it starts to harden. It starts to become a way of perception, not simply of a conjecture. This is where Whiteness begins.

So unless you know that this is a Christian operation, you cannot grasp the absolute power of race to define existence right now, even when people move beyond that Christian matrix and say they don’t confess it or agree with it. They are still inside it. That’s my definition of Whiteness: it is a way of perceiving the world and organizing and ordering the world by the perception of one’s distorted place within it. But it is also more than a perception: Whiteness includes the power to place that perception on other people and to sustain it.

How does this understanding shape the American landscape?

The challenge for these colonists when they came to the new world was twofold. One was trying to make sense of the vastness. They were seeing a world that they had only imagined existed, and it was utterly breathtaking—not only in terms of the landscapes and the flora and the fauna and the mountains and the oceans and so forth, but also the vast variety of peoples, all speaking different languages and with different ways of life. The colonists were overwhelmed by that reality.

And they had the desire to make sense of that. Why am I here? What does this mean? This combined with the reality of having absolute power. In a very short time, they came to understand that they could take everything they wanted, and this began to have a further distorting effect on their faith.

In the old world, you’ve lived your whole life in, say, a 150-mile radius, or even a 60-mile radius. Then you come to the new world. The royalty of the old world gives you 80,000 acres of land and everything that’s in it, because of your faithful service or whatever. Whatever vision of life you have with God is now shaped inside this unbelievable reality of power and greed. You hear the royalty of the old world say, This is all yours. And you hear the spirit of God saying to you, This is all yours, my son. This is your—let’s use this phrase—private property.

Now, the first thing you have to do to maintain your private property is to dispel any notion that the people who live on your land live anywhere else than on your land. Many of them had an idea that they were profoundly connected to the land, that their identities were tied to the land, water, mountains, and animals. When you would ask them who they were, many indigenous people would tell stories about the land.

For the missionary colonialist, this was nonsense. They even saw it as demonically derived nonsense: the devil was working on these people and engaging them in some kind of nature worship. So they needed to dispel this idea. This is another way that we can see—and it is really important to understand—that the modern racial vision and the modern vision of private property are two sides of the same coin.

The newly White people had to extract people from the land and extract the land from people. They needed everyone to believe that one piece of land is just as good as any other. They introduced the idea of possession—specifically, possession as private property owned by an individual who can then sell that land to someone else. For the indigenous people, this idea was utterly foreign and profoundly destructive.

Now let’s add one more layer. The colonial Europeans also brought with them commodities called slaves. Many indigenous people also became slaves as the colonies were forming. Both indigenous people and the newly arrived slaves were forced into service of the White body. They cared for its needs and attended to its moods, its forms of desire, its ways of loving, its ways of reaching out and touching God, its ways of thinking about God.

And so Christianity and the Western world form inside this ongoing, convoluted negotiation of White subjectivity, the inner life of Whiteness. For so many people, their Christianity is caught up yet inside those realities. And many people have fought against it.

Christianity itself continues to face the unfinished work of pulling itself out from inside the reality of White intimacy and out of a spiritual life that remains so caught up in what is true, what is good, what is beautiful, what is noble, what is honorable, and therefore what is desirable—from a White point of view. All of us have to go through the fiery brook of the redefinition of our desires away from Whiteness, and for so many people that fiery brook is too deep and too long to traverse. They are still caught in the midst of it.

Is it possible to move beyond race? Or do we have to go through race?

The way that the dilemma is often articulated to us is still a part of the dilemma. One of the difficulties is to get people who are White, who have made themselves White, to see that they’re actually inside something that’s been created. It’s like those old black-and-white movies, where White people are always, always in the center of the screen, and every once in a while you see a non-White person show up at the very edge.

First we have to narrate the story of those folks who enter stage left and exit. We have to put them in the center and notice how White people are pushing themselves onto a stage where they don’t belong.

But to be shaped inside of Whiteness in the West is to be shaped inside a sense of comfort and safety. Things revolve around you, and it seems to require some kind of Herculean or religiously heroic effort for you to decenter yourself.

This is what has to be challenged now. And it’s not just an idea; it’s a reality of a sense of comfort, a sense of what’s normal and what’s safe. Those realities are not just in the head. They are registered socially, economically, intellectually, academically, and especially geographically—especially in the way communities are shaped in Whiteness.

This idea of place is a major theme in your work. How are we trained to relate to place, and what are the implications for race and theology?

This is one of the most difficult things for some people to get their minds around. We have a distorted sense of what it means to inhabit place. We have been deeply habituated into what I call an unrelenting reality of displacement. This has implications for how we understand ourselves, our connectivity, our relationality, and the ethics of that relationality.

For most of us, trained in this distorted view, one place is just as good as another. You could pick us up and drop us off anywhere in the world. If we have a Starbucks and a McDonald’s, we’re good. This is not a historical accident. This is part of the trajectory of displacing people from land and turning all land into private property.

The implications are immense. Once we understand this displacement, we can see the racial configuration of place: we are inside a racial geography in which the flows of goods and services and opportunities flow around White bodies first. Then they might extend out from that to others, or they do a circuit around a few others and then back to their main source of energy.

The difficulty is to get people to understand the placement reality of White supremacy, of racial antagonism. It’s not a matter of people’s personal behaviors and certainly not of their beliefs. It is structured into the very ground itself.

We can look at this in terms of policing. All policing practice follows zoning policy. You will not change policing practice until you change zoning policy, because in the case of Black and Brown bodies, most of those killed by police either were in some place they were not supposed to be, according to the racial geography, or the police found themselves in a place they considered hostile territory. The very place itself drew their bodies into the pedagogy of violence.

We have to understand that all of our efforts at changing the social fabric of this country must begin with changing the geographic fabric. That’s where the real fight is. People will not fight you at all when you say we need to learn to love each other. But if you say that the configuration of real estate must show how we love one another, they will fight you tooth and nail.

What is your vision for wholeness in America?

I believe wholeness begins with being able to inhabit the whole story of America and the story of the West. Those of us in education mourn because so many people in this country have been given harmless history. They have been shaped inside it. People haven’t been given a full, rich sense of the glory and the horror of the Western world and of this country. They are operating in very small slices of the reality of their own lives.

Wholeness begins by starting to see the full picture. Do students see how they are born into the long story of land takeover and land seizure that continues with the configuration of neighborhoods that keep certain people in and push other people out? Are they taught the history and reality of redlining? If you’ve been to school in most parts of this country, whether private or public, you aren’t taught any of that. People arrive at college with a very thin sense of the long history of racial struggle—not just the struggle for civil rights but the struggle that takes place because we live in Whiteness. This is the struggle that comes with a particular kind of formation and conformity to a way of being.

Wholeness begins with knowing that story, because without that full story we really don’t know what to do. We’re just hoping and wishing, and for so many people it comes down to this: I just wish we could like each other, could be friends with each other.

OK, but do you understand where you are? That’s the problem for so many people in this country. They’re not even able to see the fabric. They cannot see the reality of America on their bodies.

We don’t need people saying it would be great if White and non-White people could learn to live together. That’s a useless statement. Here’s a better statement: it’d be great if we could reconfigure neighborhoods, cities, suburbs, rural areas. Then the next step is that there has to be a new intentionality about how we configure habitation and city.

One thing we have to do for wholeness is to ban all gated communities. There should not be any gated communities—they should be illegal.

What do you think that restructuring would look like in the short term, perhaps five to ten years time?

The first step is the great unveiling. For the first time probably in history for most cases, the decisions about real estate, development, how much houses will cost, where apartments will be—these decisions will be not only democratized but completely opened to everyone to see. In a process of shared governance, ordinary people will say, “Oh, hold on. I don’t think it’s a good idea to build this subdivision of homes that start at $700,000.”

Now for this to take place, there will have to be an incredible struggle—because there are people with vested interests all around us. The kind of open process I am describing is the last thing they want. Huge sectors of this planet’s land are controlled by a just few people. There are people who don’t live anywhere near where we live making decisions about what happens in our neighborhoods.

I’m not trying to evoke a new kind of nativism or provincial control. But in the short term, what has to happen is that all the decisions about place need to be made public—and slowed down so that decisions are not made without the involvement of those they affect.

Longer term, we need to create a set of standards, a moral compass, for the creation of habitation that does not exist in this world anywhere. What drives habitation is capitalism, pure and simple. So we need a moral compass to drive capitalism.

For example, we would say that no city, no town, no community may have people without homes. Homelessness is illegal: not for the person experiencing it but for the community. You have to house people; no one is to be on the street. That requires the fundamental reconfiguration of space.

We also have to think not only about property and land but about transportation of goods and services and about how bodies flow through space. We have to challenge all of that. We have to challenge the way in which municipalities structure themselves in ways that are always detrimental to those who are poor and without voice.

How do we start that restructuring?

It starts by educating yourself about who the people are who are making those decisions in your community, in your neighborhood. You say, “We want to know what’s going on. We want to understand.” Oftentimes city planning meetings are poorly attended. A few activists try to get more people to come, but folks are so busy. But that’s where decisions get made and where this moral compass is needed. It helps a lot to educate yourself about the place where you live, its history, and how it came to be configured as it is.

What would you ask the church to do?

The reality is that so many Christians in the West don’t know their own story—that is to say, that we were gentiles brought into another people’s story. What’s supposed to come with that is a sense of humility, a sense of having been brought inside by grace through love.

Our job is not to take the story over. It’s like being invited to somebody’s house, someone whom you love, and being introduced to the family. You hope they will accept you, but you’re there in vulnerability because this is not yours. You are there hoping to be a part.

Most Christians in the West are formed without any of that feeling—the sense of vulnerability, the sense of gratefulness for having been brought inside. They have no sense of what it means to be an outsider. What if we had all been inculcated with this deep sense of humility, of what it means to enter into another people? And what if we had cultivated over the centuries the ability to enter into the lives of other peoples without either trying to take their lives over or losing ourselves?

Where we should begin, individually and collectively, is reintroducing the church to the story of what it means to be a Christian: the constant entering into and becoming a part of other peoples for the sake of love. Too many Christians talk about reconciliation while imagining themselves as centered hosts.

This interview took place through the Veritas Forum, an organization that invites speakers from different perspectives and worldviews to dialogue around life’s biggest questions. A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The geography of Whiteness.”