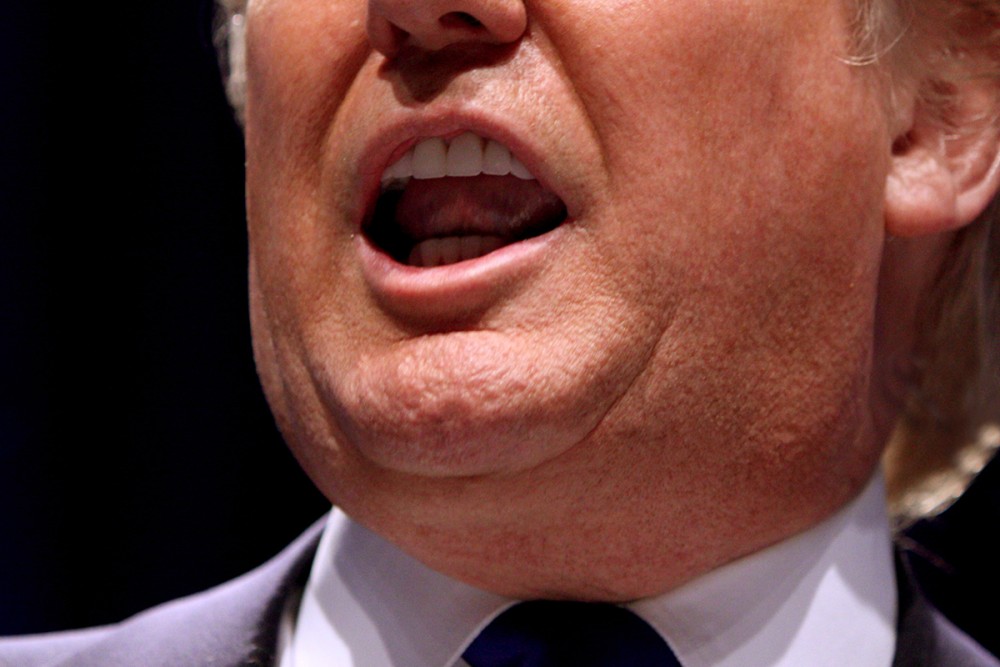

The menacing turn in our politics

Too many powerful people in public positions today refuse to repudiate the language of threat.

Something in American politics has shifted dangerously for the worse in the last decade, and there’s no excuse for it. I’m speaking of the sharp increase in verbal threats of bodily harm against people seen as an obstacle to one’s political goals. To frighten or intimidate another person into believing that they may be seriously harmed is appalling behavior. It’s vile rhetoric that sets a dangerous path for democracy. Plenty of dictators throughout history have excelled at controlling people by violent threat. What’s metastasizing in our day is the mainstreaming of menacing political rhetoric, discourse specifically tailored to instill fear.

“The darkness has reached new lows,” said Rep. Adam Kinzinger after one of many death threats to him and his family he received as the cost for his participation on the January 6 commission. And it’s not just members of Congress experiencing a spike in violent threats. Almost anybody in public service is now vulnerable to being targeted by those who respond to political grievance with personal threats. “It’s sad,” said public health official Anthony Fauci—discussing the round-the-clock security he now requires—“that a public health message to save lives triggers such venom and animosity that it results in real and credible threats to my life and safety.” In the last year, physicians, scholars, poll workers, judges, librarians, officials at the FBI and the Department of Justice, and even leaders of the National Archives have all experienced unprecedented levels of violent threat.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

There is something more treacherous than partisan rancor behind these threats to people’s personal safety. Untethered extremism deserves the blame. Donald Trump and many of his acolytes display no hesitation in going after even friends, allies, and personal colleagues viewed as disloyal to their cause. Trump’s own veiled threats that “something should happen” to his opponents or that insurrectionists who follow him are “very special people” may stop short of explicitly promoting violence. But he consistently resists appeals to disavow or discourage violence against others. Too many powerful people in public positions today refuse to repudiate the language of threat.

“We see justifications for violence that are similar on the right and the left,” notes Rachel Kleinfeld, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “But we see incidents of violence that are vastly higher on the right, and that has to do with all of the normalization of violence from leaders on the right.”

While I long for a greater appetite among elected officials to more forcefully denounce the rhetoric of threat, my primary interest is in a religious response to the crisis. Where, in God’s name, do citizens of this country, many of whom claim Christianity as their foundation, get the idea that threatening people’s safety and security has any conscionable justification? Nothing in the ministry of Jesus promotes anything resembling bodily harm or threat. He may threaten our pride by mocking the ways we serve ourselves or play God. But he never harasses or threatens anyone for failing to adopt or comply with his playbook on life. Even “when he suffered, he did not threaten” (1 Peter 2:23).

Expressing frustration with particular legislation, election results, or court rulings is one thing. Exacting vengeance on others as a consequence is quite another. When Saul breathes threats against others, he hears the voice of Jesus say, “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4). Each time we witness yet another cruel threat, we should think long and hard about who ultimately is being persecuted.