My hospice nurse’s horse

The mare pulled the meniscus in her knee. This left my nurse with a tough choice.

This week I learned that my hospice nurse has a horse, or her horse has her, as is often the case.

Some years ago, shaken by the pain, stress, and grief of getting close to patients only to watch them die one after another, she bought a horse: Holly. But Holly did not want to be ridden. Each time my nurse tried, Holly, sensing her passenger’s anxieties, became restless and rowdy. Finally, my nurse recognized the relationship between Holly’s belligerence and her own inner turmoil. She consciously chose to relax and release. She held the reins more lightly. She let Holly take control, and a beautiful, trusting friendship developed. Holly was no mere horse. She became a partner, an emotional mirror, an equine therapist.

Then Holly pulled the meniscus in her knee. The vet confined her to her stall for a couple of months, which is truly horrible for a horse and can even be deadly. My nurse was stuck between two options: continue to confine Holly or put her down. Now think about that. A career hospice nurse, philosophically committed to a comfortable and natural process of dying, faced with ending her horse’s life unnaturally, the very horse who taught her to deal with her own grief.

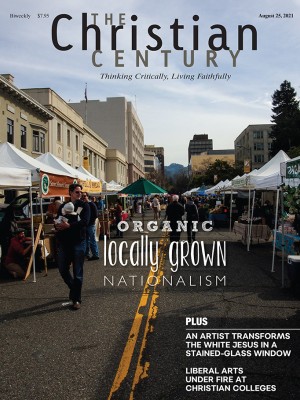

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For me, entering hospice care meant disconnecting from my fancy drugs and preparing to die. My doctor gave me a range of 30 minutes to 30 days. Then, stunningly, I dropped 30 pounds in three weeks, stopped taking morphine altogether, and got out of bed. I haven’t felt this good in two years. I should have gone on hospice months ago!

I was remembering the café scene in Groundhog Day when the Bill Murray character, who keeps reliving the same day of his life, says, “I wasn’t just blown up yesterday. I have been stabbed, shot, poisoned, frozen, hung, electrocuted, and burned. And every morning I wake up without a scratch on me. Not a dent in the fender.” He concludes: “I am an immortal.”

I understand how he feels. I have survived three pulmonary embolisms, nine deep vein thromboses, eight thrombectomies, 17 days in the catheter lab, and five general surgeries. A third of my left foot has been amputated. Throw in two open heart surgeries and three internal bleeds and you can see why hospice seemed a natural choice. I wasn’t just blown up yesterday.

I’m almost embarrassed to talk to friends anymore. People have said such kind and gracious things to me, humbling things, remarkable and heartfelt things. Now, after this hospice U-turn, I can almost overhear their inner dialogue: Well now, this is uncomfortable. Shouldn’t he be dead by now?

I wonder how Lazarus handled the social awkwardness.

My favorite movie might be Big Fish. In this feast of southern storytelling, children gather at the house of a woman rumored to be a witch, who is said to have a glass eye beneath her black eye patch. Look into that eye, the story has it, and you will see your own death. Two of the boys can’t help but look—and they see their own deaths, one falling from a ladder and the other expiring on a toilet. (Some die with dignity, some don’t.)

Would you look? Would you want to know?

I’m a pastor, and years ago I had a church member who was suicidal. She seemed to relish misery, mining it from her own life and offering it to others. Life had indeed been hard, and she was full of rage, lashing out at her ex-husband years after their nasty divorce, estranged from her adult children who had grown weary of her aggressive despair. You’ve known glass-is-half-empty kind of people. Well, she had thrown the glass at the mantel.

My advice to her was not conventional. In fact she is the only person I have ever known to whom I would say what I said. “I understand that you want to die,” I said. “And truth told, no one can stop you if you decide to take your life. We will be sad, but we cannot stop you.”

Then I asked, “But what’s the hurry? You have the rest of your life to end your life. Why not wait around to see how really awful it can get?”

We sat together in silence. Then she smiled. Thank God. And I’ll be damned if she didn’t hang on and then remarry and live quite happily until her death some years later.

The mystery of how things wrap up can unleash energy and unexpected joy for each day. Think about it. If you stop a chatty friend before he ruins the last episode of Game of Thrones or Schitt’s Creek, why would you want to know the details of your final moments? Where’s the fun in that, the meaning in that, the humor in that, the faith in that? Gazing into the witch’s eye is the ultimate spoiler.

Trusting God is the ultimate spoiler alert.

Still, I remind myself that I must remind myself of this. Some days the affirmation is a bit shakier than others. And then my wife enters the room, or one of the kids does, or the phone rings, or a new thought dazzles, or Eric Clapton pops up on my playlist, or I FaceTime a friend—and then, somehow, life’s expansiveness becomes perceptible again.

I can see how some hospice patients reach the tipping point, and it is time for them to go, so they release. But also, it seems to me that waiting to see how things turn out doesn’t require persistence so much as patience. They’re vastly different things. Persistence is an act of will. Patience is a relinquishment of it.

So as for me, I’ll stay, at least for a while.

My nurse decided to put Holly down. Then the vet called with good news. While Holly could never be ridden again, she could be released from her stall and allowed to wander the pasture.

My nurse still visits Holly. They walk the fields, and sometimes she brings Holly to a picnic table, where she sits and talks to her while the mare grazes nearby.

Turns out, grazing has its purposes. “Meanwhile,” writes poet Rachel Wetzsteon, “is far from nothing.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “My lengthy hospice.”