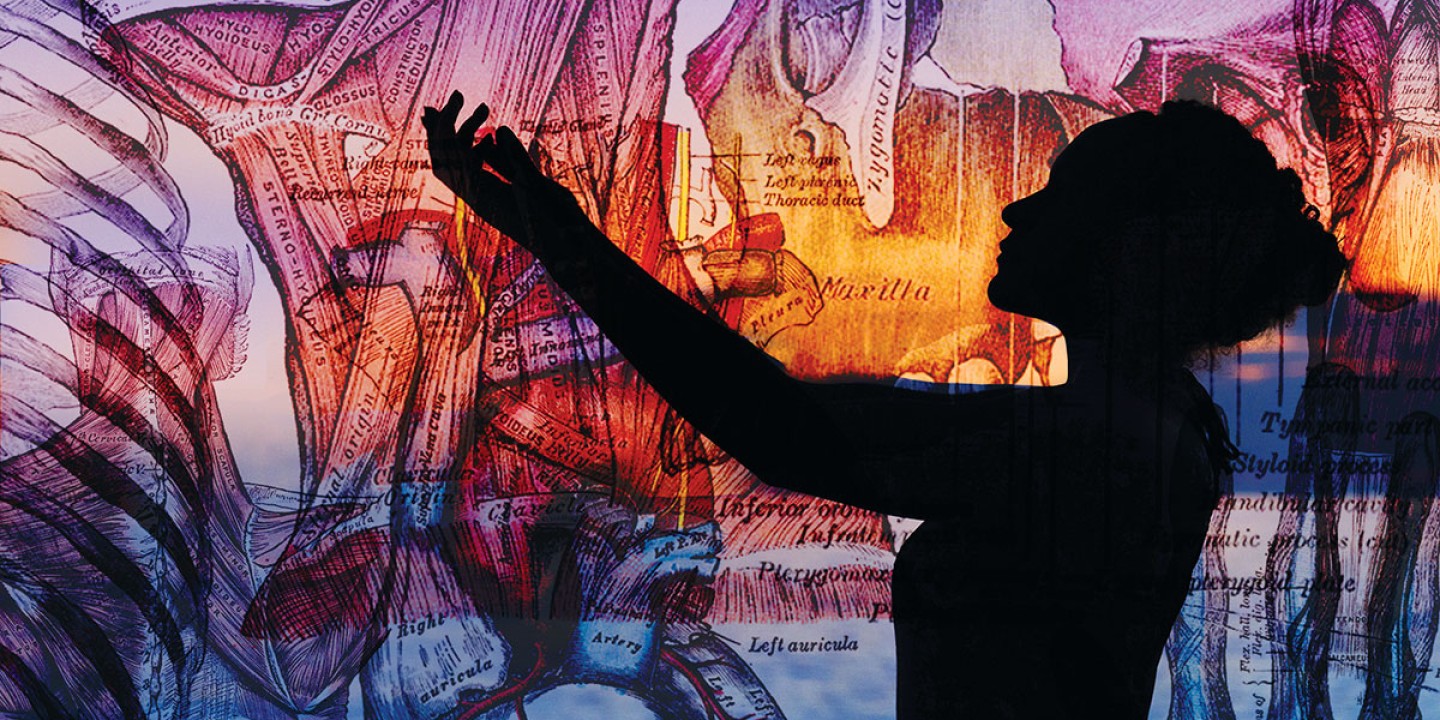

How I came to love embodied prayer

I tried it—and I began to experience God in places other than my head.

I suppose I learned to pray like many people in the mainline church do: I memorized prayers for mealtime and bedtime, and I listened to what felt like the excessively long prayers of the people at church. I didn’t have anything against any of these forms of prayer; perhaps God did bless the hands of those who prepared the food, keep my soul at nighttime, and intervene with world leaders and natural habitats. I just couldn’t see any results. God must not be in the business of speaking back, I concluded.

As I grew into adolescence and started hanging out with evangelicals, I learned a new way to pray: long, wordy outpourings interspersed with “just” pleas: “Lord if you would just . . .” the prayer would begin. I was expected to pray this way as often as possible, in groups and in solitude, and I filled journal after journal with outpourings to God. God was the Great Listener, the one who required total honesty. Perhaps my disproportionate speaking got in the way, but God, it seemed, was not in the business of speaking back.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In seminary, I tried centering prayer, labyrinths, meditation, and yoga, fascinated by the friends who felt a deep sense of peace in these quiet practices. But my mind chattered through them, reminding me of things still to do, working through a theological quandary, or chewing on a conversation from earlier. If I could just learn to quiet my mind, I would think. But my mind is the chattering type, and God, it seemed, was not in the business of interrupting.

In my fourth year of ministry, a friend encouraged me to try a new spiritual director who worked almost exclusively with clergywomen. After listening to me talk in theological circles for months, Anne gently interrupted. “What about prayer?” she asked. I sighed. I wasn’t interested in learning yet another prayer practice at which to fail. I had not given up on prayer, but my expectations were low. After all, I thought, God didn’t seem to be in the business of speaking back.

But Anne could see what I could not: that my faith was primarily one that lived in my head. Thinking, learning, and study were my fortes, avenues that faithfully led me to God. I had always been able to sense God’s presence in a good Bible study, a challenging theology class, or even in the thrill of writing a sermon, where a creative force felt almost palpable. It wasn’t that I didn’t have a sense of God’s presence in my life; it just didn’t come through prayer.

Anne wanted to teach me to move prayer from my head into my body. God lives in the deepest parts of you, deeper even than your thinking, she would tell me. She outlined the process: We would begin with a period of deep breathing, followed by a body check-in (letting my attention wander from my head to my feet, checking in at each space). She would then invite me to listen to where my attention was drawn, then to listen for an emotion, then to listen for a story (not telling a story or analyzing a story, as I was first prone to do, but simply listening to what comes). The process would end with a period of reflection, holding the question, How might God be speaking to you through that story?

I was skeptical. But the first time she led me through it, I was startled by how deeply I was moved, by the sense that I was engaging with God in a way I had never before imagined. I was a new mother then, exhausted by the sheer physicality of pregnancy and birth and recovery and nursing and sleep deprivation. “Where is your attention drawn?” she asked, as she guided me through the body check-in. “My abdomen,” I said, surprised. “And what is the emotion there?” she prompted. “Tenderness,” I responded immediately. “Whose?” she asked. “God’s.” I responded without thinking, overwhelmed by the sense that God was offering God’s own nurture and tenderness in the places where my tired body had nurtured life.

I blinked open my eyes, startled. “What just happened?” I asked. “Prayer,” she responded softly. I cried for a week.

The more I practiced embodied prayer, the more I came to trust a deeper wisdom. When the opportunity for a new call came up years later, I agonized over the decision, listing the pros and cons, consulting the advice of mentors, and Zillowing houses in the area to see if we could imagine living there. But my discernment remained murky, and after several weeks, I still had no clarity.

On the day that my decision was expected, I returned to embodied prayer, listening to where my attention was being drawn. As I blinked open my eyes, I was once again startled by how clearly my gut had been holding the answer: no. I immediately phoned the call committee and declined to move forward, perfectly at peace with the decision. God had been speaking through my depths.

I am nearly always surprised at what embodied prayer uncovers. Last year, near the end of a much needed but restless sabbatical, I found myself floating in hot springs, again at the urging of my spiritual director. The water felt warm and enveloping, and I felt called to prayer in the midst of the hottest pool. As I listened to where my attention was being drawn, I felt the warmth of the water move inward, into a deep sense of soothing, a quieting of my spirit alongside an embodied feeling of joy. The rest for which I had been searching for months bubbled up within me, surely a gift from God. That feeling of rest would change the course of my sabbatical and ministry.

“There is a place in the soul that neither time, nor space, nor no created thing can touch,” said Meister Eckhart. Embodied prayer brings me to that space. Recently, at the beginning of another call process, I again turned to embodied prayer. This time, I felt a sure presence on my chest, warm and opening, as if my heart was expanding. The weight was firm but not heavy, and I was struck by how strongly it called my body back to the feeling of a sleeping child resting against me. I felt simultaneously ready for a new challenge and at peace that this was the place I was being called. God was again speaking through the deepest parts of me; it was easy to say yes this time.

Sometimes embodied prayer uncovers joy, sometimes sorrow, sometimes peace, sometimes connection, sometimes strength, sometimes my own history, and sometimes nothing. I am still learning the practice, still surprised each time at the intimacy of God’s presence and the sanctuary that God has carved within.

It turns out God was indeed in the business of speaking back; I just needed to discover how to listen.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “God speaks into my body.”