Bruised and blessed by scripture

My hermeneutic of suspicion wasn’t enough. I needed a hermeneutic of the hip.

By the time I got to seminary, I’d had years of experience defending myself against Christianized homophobia. My life was a walking answer to “How do you reconcile your sexuality with the Bible?”

My best answer was that the scriptures had nothing to say on same-gender relationships. The Bible couldn’t speak on queer people in the same way that we could not ask it about best practices for automotive design; the information simply wasn’t there. The writers of the scriptures had no working concept of sexual orientation or gender identity, nor did their interpreters for the next 1,800 years. Even the instructions for heterosexuality were ragingly outdated; women have the right to initiate divorce now, for example. And who was going to keep track of who sat in what chair during what time of the month? The Bible was a collection of our faith ancestors’ best attempts to describe their encounters with the divine, but just as we were hindered by our own time and place, so were they. The culture was just too far away for us to derive anything meaningful from it, not without a significant amount of context, and even then all that we knew should always be questioned.

This was the interpretation I rested in for years. It protected me from the spiritual violence dealt upon my fellow queer family; it resonated with my understanding of feminist critiques of the texts. It wasn’t impossible to still find meaning in the Bible; it was like a museum piece, one that still confessed to realities about humanity and, if investigated well enough, to how that humanity had once experienced God. There was enough in religious practice—worship, prayer, fellowship—to keep me grounded even when Bible study set my teeth on edge. I developed a spiritual allergy to words like inspired. I felt anxious and itchy around people who talked about “their walk with the Lord” or who came to worship carrying heavily highlighted Bibles. As a seminarian and then an intern pastor, this distrust was a constant companion.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In my feminist theologies class, I was given a name for my distrust: a hermeneutic of suspicion. Built on the work of Paul Ricoeur, it captured the modernist practice of distrusting self-proclaimed truths and looking instead for omissions and inconsistencies. In feminist theologies, it meant an awareness of the patriarchal and misogynist societies in which the scriptures were written and formed, and a continual open identification of where women and other minority voices had been silenced.

But eventually the word suspicion began to fall short for me. It had come from a straight white man summarizing the modernist tendencies of other straight white men (namely Freud, Marx, and Nietzsche). Suspicion seemed like a philosophical hobby for those so burdened by their own privilege and genius they had to find something to occupy their time. This was not a parlor game for me, a murder mystery to page through warm by the fireside. This was, as Episcopal priest and author Broderick Greer would name it, a hermeneutic of survival. I had to find a way to cope with the violence of scripture, both what was literally contained within its pages and how it had been used to wound people over 2,000 years of cultural domination. I would not be able to exist within the church if I could not find a way to read the stories of its faith.

I stayed in the Gospels and Acts as often as I could, focusing there for preaching and Bible study and essay metaphors. There, I could join with Jesus in his ire toward the religious elite. I could also balance respect for the historical meaning of scripture with an awareness that its legalistic application could mean further harm or death for those who were already in distress. You tithe mint and dill and cumin, but neglect the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith! The prophets could be safe, especially the justice-oriented books like Amos and Micah, but if I was not careful enough I’d find myself in the whore language of Ezekiel and, once again, have to shield myself with Hebrew grammar books and historical-critical critiques until I could find a way into safety—which was usually anything in the category of “not the Bible.”

I did my best to hide my fear of the Bible. Some of it was respect for others; I didn’t want to burden those who had no issue with it. But just as much (or more) was my own exhaustion. I was tired. I was tired of explaining myself to everyone. I was tired of feeling my walls shoot up in every conversation, tired of distrusting every new acquaintance who showed a little too much interest in my religious beliefs. I was tired of lying awake at night coming up with new and multilayered metaphors for explaining how I could reconcile the “clear voice” of scripture with my “lifestyle choice.” I was just tired. It was easier to pretend that scripture and I had a happy marriage where all our concerns had long ago been resolved and we were now working together in perfect harmony toward a better proclamation of the good news throughout the world.

And then it all unraveled under the weight of 14 words. It was a simple quote out of a lecture at the Festival of Homiletics, by author and theologian Lauren Winner: “What if our job as preachers is to just love the scriptures in public?”

And I felt my heart crack down the middle. “Loving the scriptures” was an impossibility. The scriptures were a receptacle for every queer- and transphobic, misogynist, white supremacist, and otherwise power-hungry excuse for violence and destruction over the past 2,000 years. I could dig a gold nugget out of that pile of rubbish if I worked hard enough, but I was never going to love it. No one could love a weapon that has beaten their family black and blue.

I carried my self-protective anger for days. Who did this Dr. Winner think she was? She might have escaped the ravages of “Christian” practice to be able to claim this vile “love” for the scriptures, but imposing it on others was just doubling down on the cruelty. Yet another sign of the violence inherent in the system.

I was angry because I knew she was right. I knew that I was burning out. Others lived and even flourished with the hermeneutic of suspicion, but it was eating me alive. My self-protective shield against scripture had turned into a burden I could not carry. I had been working full time for ten years to put my life into ministry, to testify to the presence of some sort of truth and reality in scripture, despite the fact that I didn’t believe in its literal King James perfection. I needed more than suspicion. I needed more than survival. I felt bitingly jealous of those who did not.

I did not have a plan for how I would accomplish falling in love with scripture. I simply decided that I had to and went from there. I bought a new Bible—New Revised Standard Version, the size of a hymnal, with no study notes or margins to speak of. This was not a scholastic project. This was not about worship or preaching. This was about falling in love.

I started on page one and just kept going. I was on a schedule; I had to get through the whole of the Bible in 90 days, which meant about 16 chapters a day. There was not enough time for in-depth consideration of the Hebrew or a deep scholastic dive on each verse. Some days I would have to go through multiple books at once. If an idea struck while reading, I had about five words’ worth of space to make note of it. If something resounded with me, I highlighted it. And I just kept going, 16 chapters a day, 90 days in a row.

I treated the Bible like I treated Harry Potter or Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Star Wars or any other story with multiple volumes and characters I loved. It was made by humans. There would be mistakes. But the creators were trying to convey something beautiful, something important, something true, and if I could believe in good intent on their part, I could believe it for the authors of the scriptures as well.

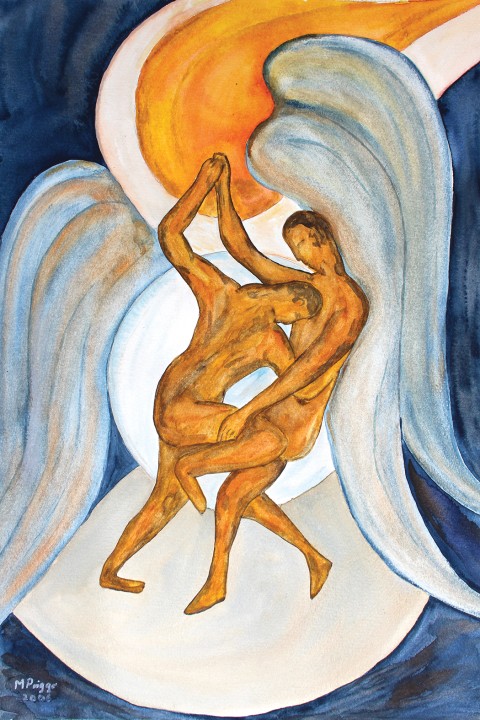

Three days in, I found the story that would come to guide my new relationship with the scriptures: the story of Jacob and the man who wrestled with him. Having stolen his brother Esau’s birthright and blessing, Jacob served his uncle Laban for 20 years, but he caused enough trouble for himself there that he decided to return home. He sent messengers ahead to his brother, who then came out to meet him with 400 men—an army, Jacob was sure, that would overtake him and his wives and children and destroy them for the injustice done to Esau. Jacob prayed desperately for God’s protection and then sent an enormous flock of goats and sheep and camels and cows ahead of him, hoping for his brother’s mercy. He then sent his wives and concubines and children across the river and stayed by himself for a sleepless night.

A man appeared—no description, no buildup, only the sudden existence of an enosh who wrestled Jacob all night until dawn. The man could not beat Jacob—in many interpretations of the story that meant Jacob was winning—and so he struck Jacob on the hip, crippling him permanently. Still Jacob persevered, pinning the man: “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” Fine, said the stranger. Here’s your blessing: you are no longer Jacob, heel-grabber, trickster, one who takes what is not his own. You are now Yisra-El, for you have striven with both God and with humanity, and you have prevailed. Jacob—no, Israel—would never walk properly again; but neither would he be the man who had stolen his brother’s life and incurred Esau’s murderous wrath. When daylight came and Esau arrived, he fell on his brother Jacob-Israel’s neck, weeping with joy to see him again.

I knew the dread that Jacob had felt. I knew what it was like to abandon what I had known for a new land. I refused the binary offered me of choosing either my faith or my sexuality, loving Jesus or loving my future wife. I had made a new way for myself, in college and seminary, finding my own voice and claiming my own gifts. Each time I opened the scriptures I felt a raw fear, like I was staring down my own destruction. I was going to have to make peace with this, with scripture, with a holy book that would be used over and over again to wound me and my queer family.

Some days the scripture I read would eat at me until nightfall. Some nights were sleepless or restless. I knew what the psalm writers had wrung from the depths of their heart: I am weary with my moaning; every night I flood my bed with tears (Ps. 6:6). I kept going. I kept reading and tossing and turning. When scripture kept me up I stayed up with it, unwilling to quit, exhausted but still holding on. I felt the wounds again, the thousands of years of abuse that scripture had been twisted to encourage. My heart beat with a limp. I still would not give up. I will not let you go unless you bless me, I whispered again and again. There was a blessing in the story—I had to believe this—and if I had to pin it down and sit on it until it cried uncle, I would do it. I would wait for the dawn, for scripture to look me in the eye and say: You are not what everyone else says about you. And I would wait and trust that one day, the enemy that was the church would embrace me, falling on my neck and weeping with joy at our reunion.

I would come to call this way of reading the hermeneutic of the hip. The fall after I completed my 90-day journey, I came across an essay Phyllis Trible had written in Biblical Archaeology Review called “Wrestling with Faith”:

Jacob’s defiant words to the stranger I take as a challenge to the Bible itself: “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” I will not let go of the book unless it blesses me. I will struggle with it. I will not turn it over to my enemies that it curse me. Neither will I turn over to friends who wish to curse it. No, over against the cursing from either Bible-thumpers or Bible-bashers, I shall hold fast for blessing. But I am under no illusion that blessing, if it comes, will be on my terms—that I will not be changed in the process. . . . The storyteller reports: “The sun rose upon him [Jacob] . . . limping because of his hip.” Through this ancient story, appropriated anew, Biblical studies, faith and feminism converge for me. Wrestling with the words, to the light I limp.

This was a metaphor that could sustain me. It took me beyond suspicion or survival. It looked beyond “wrestling with the text.” It recognized the danger in every time I opened the scriptures, every new encounter with a fellow Christian, every brutal beating that had been given in God’s name throughout history. This story affirmed wrestling and its results—it reminded me why I trusted those best who were unafraid to name their own struggling with the scriptures and the church. We have diverse causes, a variety of experiences, each our own individual traumas, and yet in our many ways we bear a similar scar, a joint out of place, a blessing with a new name that saw our striving and called it wrestling with God. My family on the margins—queer and trans, but also women, people of color, the disabled, the poor and hungry, the refugee and outcast, my fellow sufferers of mental illness—has known what it is like to wake up day by day in a life that challenges the easy promises of American Christianity, a life that lived even to its best can never overcome the adversity laid before us simply by “trying harder.” We know the truth: sometimes coming face to face with God sends us away bruised and yet blessed.

Some of us walk away forever. There is too much wounding. I carry with me many stories of those who have found no more blessing in the struggle. The church, the scriptures, God are all too wounding still. It is my responsibility—and, I believe, the church’s—to bear these stories, to witness to them and face unafraid the truth of what has been done in the supposed name of God. We are to honor these stories. To fear and silence them is to ignore the presence of God, who meets us not just in glory but also in suffering, who to give a blessing did not pronounce it from rendered heavens but whispered out a new name, pinned in the dark before the dawn.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Bruised and blessed by the Bible.” It was excerpted from Emmy Kegler's book One Coin Found: How God’s Love Stretches to the Margins, forthcoming in April from Fortress Press. Used by permission.