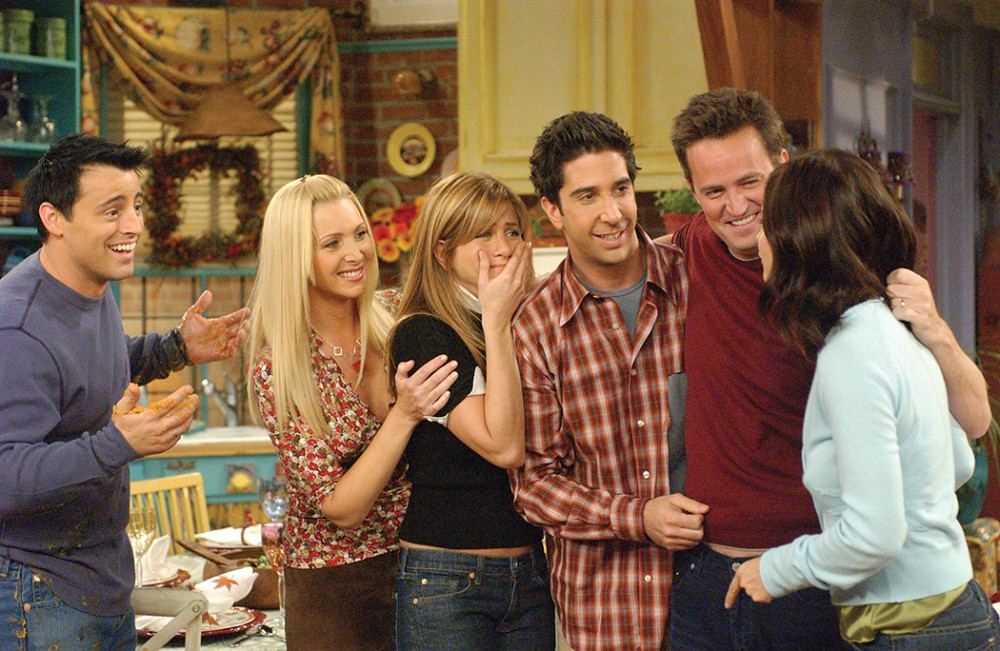

The one where the characters on Friends talk face to face

Millions of young adults are watching Friends reruns. Why?

College students are obsessed with Friends. Not their real-life buddies, but the sitcom, whose 236 episodes dominated American TV from 1994 to 2004. Though Friends displays the kind of homogeneity younger millennials and Generation Z rail against—it’s an all- white, heterosexual, middle-class, and able-bodied cast—they are nevertheless enthralled by it.

Nearly 16 million people watch Friends reruns each week. Netflix purchased all the episodes in 2014. The New York Times reports that 81 percent of Netflix account holders are adults under 35. Viacom also cashed in: within weeks Friends became its top-acquired MTV program, attracting more new viewers to the network among people 18 to 24 years old and even more new viewers in the 12-to-17 category.

Why would media giants spend millions to acquire an outdated show? In his Vulture essay, “Is Friends Still the Most Popular Show on TV?” Adam Sternbergh writes that young adults find Friends entertaining because of its now-impossible premise: six young Americans take time to talk to each other in person sans cell phones.