How are dinner churches surviving the pandemic?

For some congregations, sitting down together for a meal is the heart of worship.

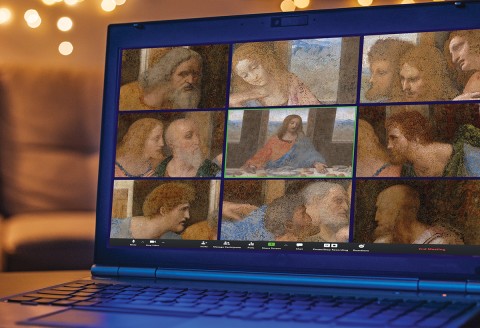

“Welcome, everyone, to Simple Church!” Pastor Zach Kerzee shouts into the camera, guitar strapped across his chest. Kerzee sits at a dinner table set with steaming mugs of tea, glasses of grape juice, and hunks of home-baked bread. His kids wriggle in their seats, play instruments of their own, and take turns climbing into Kerzee’s partner’s lap. Streaming to the congregation over Facebook Live, Kerzee encourages members to gather around a meal with their own households as well.

Kerzee is the founding pastor of Simple Church, a United Methodist dinner church in central Massachusetts. Modeled after the early church practice of sharing a meal together as Eucharist, dinner churches seek to address social isolation and loneliness through the very structure of their worship. Their practice also mirrors the agape meal or love feast tradition, a tradition adopted by John Wesley and memorialized in the UMC Book of Worship. Over the last decade, dinner church communities like Simple Church have sprung up across North America, holding their weekly worship over the course of a meal.

When COVID-19 hit, these innovative pastors—like pastors everywhere—were forced to shift their meetings online. With their focus on intimate relationships and participatory worship, virtual dinner services have become a means of nourishing communities both spiritually and physically for the long-term separation necessitated by the pandemic.