Godly Play and the language of Christian faith

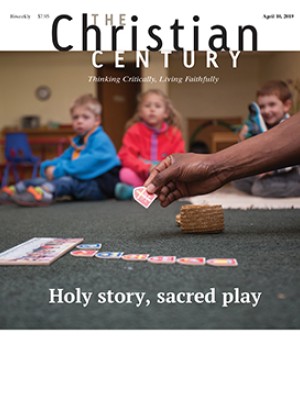

At the heart of each lesson is storytelling and wondering.

If learning to be a Christian is like learning a language, then teaching children to speak Christian is more complicated than it used to be. Families don’t go to church as much as they once did, and the culture does not naturally support Christian speech or Christian ways of thinking about the world. When children seldom hear the Christian language spoken fluently, they can’t absorb its structure, function, and content. They learn only bits and pieces to carry with them into adolescence.

Teaching children how to speak Christian is something I’ve been working on since 1960, primarily through an activity called Godly Play. Godly Play is a process of leading children into a form of deep play that leads to wonder, encourages them to ponder the source of the wonder, and allows for their insights to emerge. Godly Play invites children in to a beautiful setting and uses well-trained mentors to show children how to speak Christian.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Children learn new languages easily because they uncritically absorb what’s around them. They take what they experience in church and associate it with “Christianity.” The associated feelings get buried as the years go by, but it is always deep inside them as part of what it means to be a Christian. This is why it is so important that the foundational aspects of Godly Play are laid out intentionally and also beautifully.

In that light, consider the room in which children gather to learn about God. The room communicates simply and nonverbally what your church finds most significant about Christianity. Is the room beautiful? Does it stir wonder? Is there a warmth and welcome to it? Is it well cared for? Is it safe? Does the space highlight the importance of our sacred stories, parables, and liturgy? Is there room for silence?

These questions are important, because young children can’t take the larger perspective about a room that adults can. This is why the room for the youngest children needs to be the most carefully maintained of all. Just as we learn finer points of grammar as we age, Godly Play classrooms become progressively more complex as children get older.

The materials in a Godly Play classroom are simple and well organized. Art supplies are of the highest quality and are ready to use. Snacks are prepared and in easy reach when needed. The sacred stories, parables, and liturgical action stories are each contained neatly in their own box or basket. Each box contains a number of engaging objects to help tell the story or rehearse an action. The stories, in turn, are housed on shelves representing the Christian language system.

At the center of the shelves is the baby Jesus in a crib surrounded by the Holy Family. Behind the crib stands a cross. On the left are the lesson materials about baptism and on the right are the materials for teaching about Holy Communion. On a shelf below the central image is a representation of the circle of the church year which guides the use of Christian language week after week.

Learning languages requires consistency and patience. Mentors in the Godly Play classroom help guide this process. When the children come to the door, they find a door person sitting there in a little chair at their eye level. This person quietly helps the child slow down and prepare to cross the threshold to enter the world of Christian language. Christian language does not function well unless you slow down and are centered. We need to be still to know God, as Psalm 46 says.

When the children are ready, they enter the space and sit in a circle, anchored by a second mentor, the storyteller, who will tell the story appointed for the day. The storyteller sits on the floor with them in front of the shelves holding the stories.

If you are a child you can actually see your church’s theology from the moment you sit in the circle, waiting for the story to begin. A large Bible holds a prominent place. Even for children who can’t read this is a powerful symbol of the centrality of the Word. Liturgical action stories help to connect our way of worship to biblical stories. The story of baptism is located to the left of Jesus, and the story of the cross and Holy Communion are to the right. The shelf for Advent and Christmas is next to baptism, and the shelf next to Holy Communion is for Lent and Easter. The Pentecost shelf is nearby.

Materials are ordered so that children never need to unlearn something in order to take a next step. Biblical stories are shelved chronologically; Hebrew scriptures on the left and the New Testament on the right. This is the Great Story that begins with creation and ends with an empty book on a stand, which symbolizes the part the children will write themselves. On another wall are the shelves with materials on the parables. Liturgy enacts how Jesus taught by the mystery of what he did, as a kind of living parable. But he also taught with words and stories. These are the basis for a series of parable boxes, mysterious stories that are descriptions of the kingdom of God and gifts passed down through the generations. As children move through the calendar of the church year, through the Old and New Testament, and into the mystery of the liturgy and the parables, they recognize patterns and grow in confidence in the use and interpretation of materials.

In the center of the room is an open space where children form a circle and hear a story. This is also where, alone or in groups, they create their own artistic responses to the story they hear and wonder about.

After the response, it’s time for the feast. The children put their materials away and return to the circle. Two children are selected to help serve the juice and cookies. Everyone waits until all are served and prayers are said. It is here that children learn and model Christian table fellowship. This is sometimes the occasion to sings songs or learn passages of scripture by heart, such as the Lord’s Prayer or the Twenty-Third Psalm.

When the feast things are put away, it is time to get ready to say good-bye. Then the children get quiet so that when the door person whispers each child’s name, that child can get up and stand in front of the storyteller. The storyteller offers an informal, face-to-face blessing of each child, perhaps saying, “It was wonderful to have you here.” The door person helps the children cross over the threshold to meet the people waiting for them.

At the heart of the session is the storytelling and the wondering. Stories include specific objects and carefully written scripts. A storyteller is fully immersed in the story, telling it by heart. Children do not interrupt the story until it is time for wondering together. If individual children need attention during the story, the door person might assist them, but this is rarely needed. If the space is well organized and the mentors have set the tone with respectful wonder, children are eager to listen to the story and delve deeply into their own spiritual practice.

To suggest how storytelling might work, let us consider the story of creation.

A storyteller always begins by getting a story from a specific place. The storyteller will go to the shelf where the creation story is, explaining to the children that he is showing them where it goes so that they can come back to it later.

The storyteller tells the story of creation by presenting the materials piece by piece. In this case, a piece of black felt is used as an underlay and plaques or cards are used to represent the days of creation. The underlay helps to indicate progression: the story has a beginning and an end, and the plaques of the days of creation will fit on it. The storyteller then holds up the first plaque depicting a simple drawing of light and dark and says something like this: “On the first day God gave us the gift of light. This was not ordinary light. It was the light all the rest of the light came from. When God saw the light God said, ‘It is good.’” The children might be invited to touch the plaque as it is carefully laid on the felt underlay, like giving a blessing. All the rest of the days of creation are presented in the same way. When the seventh day is named, its plaque seems to be blank. What a surprise! Sacred stories are filled with surprise and even humor, which the storyteller highlights. The storyteller then shows that the day God rested is not empty but is rather marked with a star by some, a cross by others, and by other symbols. He draws them with his finger as he speaks.

The storyteller then sits back and begins the wondering, inviting the children to wonder along with him. “I wonder what part of this story you liked best?” “I wonder what part is the most important part?” “I wonder where you are in the story?” “I wonder if there is any part of the story we can leave out and still have all the story we need?”

These questions follow a natural progression that helps children ease into the wondering (we all know what we like best) to larger issues (what is really important?) to making the story about ourselves (where am I in this story?) to the great existential questions of limits (what can we leave out?). It is not unusual for a child to respond to these questions with deep thoughts about the meaning of life, the nature of our call as Christians, and even the mystery of death. A storyteller does not correct or offer easy answers; instead he holds space for the children to wonder by wondering himself. Other children may add to the wonderings of others. This sacred time is Spirit-filled and conveys the deep work of Christian life.

Sacred story speaks to sacred story in the Bible. Just as metaphor and analogy heighten our experience of language, the Godly Play process encourages us to see how stories relate to each other. Children may find connections between a sacred story and a parable, liturgical action, or a life experience they have had. This is good and holy work.

After the wondering together, children are invited to work on their own or in groups on a response. This is an opportunity for children to continue working with stories that intrigue them or to produce something new based on what they have experienced. Unlike an ordinary Sunday school classroom, children are invited to work on the same story for as long as they like. Children are individually invited to choose their work, normally working alone.

Children’s work will be very quiet. The mentors do not circulate through the room to see what children are doing. Work is private and done for its own sake. If a child presents his or her work to the storyteller, the storyteller talks about the work with the child. There are no value judgments about the work. (We are often tempted to talk about a child’s work as “good.” How do we know that’s what the child had in mind?) It is better to say something like “That’s so red!” or “There are many sheep,” or “I wonder how you feel about this work?”

The doorperson and the storyteller are aware of what is going on and are on hand to help children get ready to work. While helping and anticipating problems, the adults do their utmost to stay out of the children’s way and let them do their work. This is how children make Christian language their own.

Christian language has four main dimensions: liturgical action, parables, sacred story, and contemplative silence. The first three are part of the materials that are literally sitting on shelves in the room. Where does silence come in? This is a question we also ask the children. Sometimes the storyteller walks around the room touching the various parts of the room and saying: “Here are the sacred stories. Here are the parables. Here are the liturgical action materials. But where are the silence materials?” This question is left hanging in the air, but it is not forgotten. Children learn to find the silence they need and to sense when silence comes close to them.

Contemplative silence with God plays with sacred stories, parables, and liturgical action to make the whole language system work. When the system is fully functioning it can help lead us into maturity—or, as Jesus said, into the kingdom of God.

Godly Play has two kinds of goals. One is to work year by year at the long-term development of the children toward fluency in Christian speech, so that children can enter adolescence with an inner working model of the Christian language system. These are the tools that will enrich their adolescent identity, which in turn provides them with the means for lifelong learning about being Christian. The other goal is the more ambitious and is not within our control: to use Christian language to open the door into God’s kingdom.

The river of the creative process flows out from and returns to the Creator. John wrote about this while living on the island Patmos. He saw a “river of life” that flows “through the middle of the streets of the city.” He wrote, “Let anyone who wishes take the water of life as a gift.” The river is a gift, but we must cooperate with the flow of God’s creativity to find it. We need our Christian language and community to discover how to move in it as it moves in us.

To live in the deep channel of this river we need the support and insight of the whole system of relationships in Christian language and the community of the church. Like all language, there is a process of conversation inherent in the system. If the openness and structure of God’s creativity become uncoupled, then God’s gift erodes. Openness by itself becomes chaos and madness because it lacks structure. Structure by itself becomes rigidity. The sacred stories and the bubble-bursting energy of parables keep us open and yet define us as creatures in community who create in God’s image. Silence grounds us in the places too deep for words.

Over the past 40 years I have seen children move into the deep channel of this river of life at a very early age. They move by intuition. As they gain fluency in Christian language, their moves become more conscious and they become less likely to get stuck in rigidity or chaos. They can live the life that Jesus called us to live.

Godly Play is a face-to-face and intimate art. You can’t mail it or push a button to do it electronically. It is not something that takes only 15 minutes to prepare on Saturday night. It is an art you can improve on all your life. We are all storytellers, but this natural ability can be lost. We are all designed to create meaning, and yet the art of wondering is forgotten. A Godly Play program needs the same effort and commitment that it takes to create and maintain beautiful and meaningful worship for adults. And just as the commitment to creating meaningful worship reaps its own rewards, so too teaching our children the language of faith has deeper benefit than we can imagine. Jesus said that if we would welcome his kingdom, we must do so like a little child. In teaching children the language of faith, we enter into the mystery anew.

Learn about resources on Godly Play.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Holy story, sacred play.”