The bones of Jacques Marquette

The Jesuit explorer was a friend to Native Americans. At last, he’s going home.

It’s a cloud-covered March afternoon just off Milwaukee’s bustling Wisconsin Avenue. Visitors, students, and tourists mill around the borders of a terraced garden park. Their focus is Marquette University’s St. Joan of Arc Chapel, a small, picturesque, 15th-century stone structure. A stylish brochure informs readers that in the early 20th century, a wealthy donor made it possible for the chapel to be transported stone by stone from its original location in France.

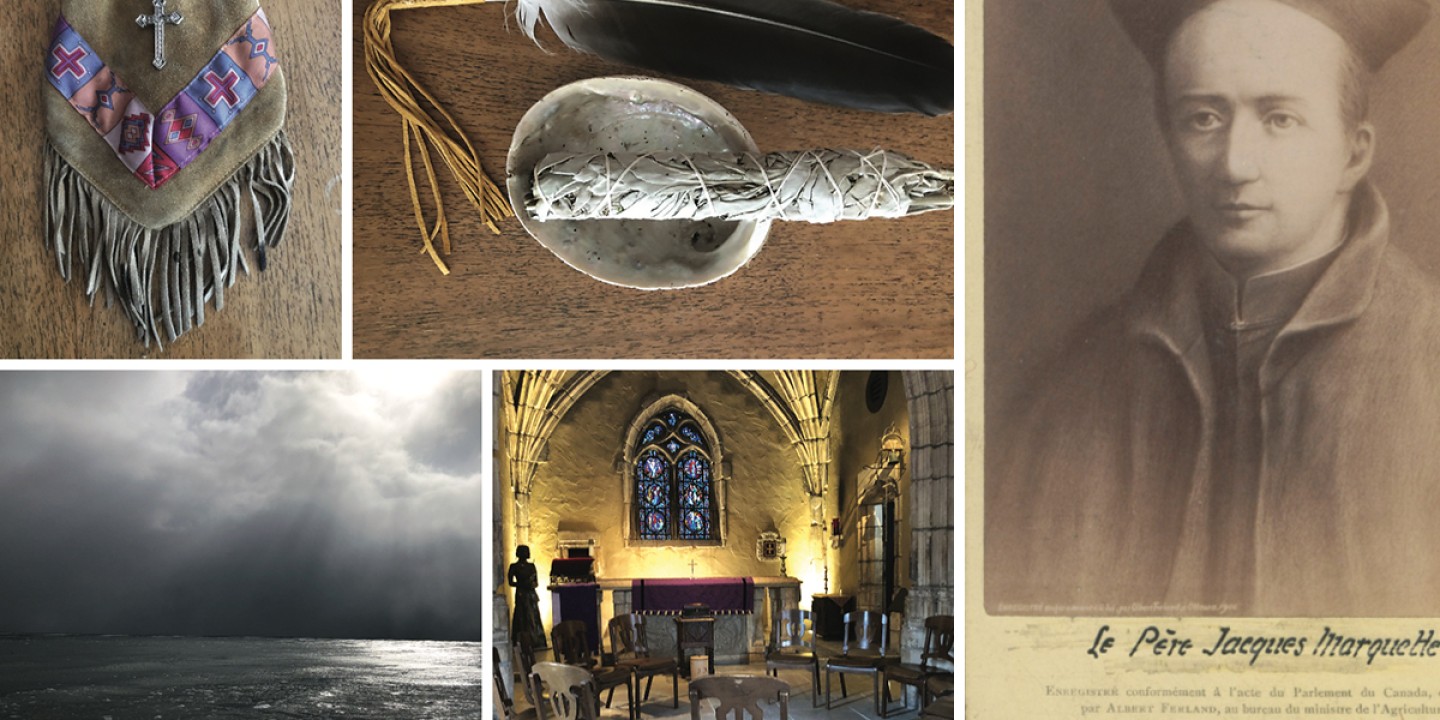

This day is not an ordinary day. Shortly after 1 p.m., two Native Americans from St. Ignace, Michigan, 370 miles away, stand a few yards in front of the chapel’s entrance, dressed in ribbon shirts. They begin to blow into whistles made from the bones of eagles.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These two visitors, who traveled here yesterday from the far reaches of the Great Lakes Basin, are not in a hurry. One is the sexton of an Indian cemetery, the other a traditional Anishinaabe elder. They turn intentionally to each of four directions. Sounds from the two thin whistles—high-pitched, singular—pierce overcast skies.

The purpose of this delegation and this ceremony is to transfer the remains of Jacques Marquette, a 17th-century Jesuit priest, to northern Michigan and to the native peoples who originally buried him at the Straits of Mackinac in 1677. In a service of prayer and dedication, representatives of these native peoples are joined by representatives of Marquette University for the transfer.

The event is intended to be a quiet affair. Secular press are not invited. As we are escorted into the chapel’s interior, the structure’s two large wooden doors are slowly closed to the curious stares of passersby.

In the 17th century, a select group of 46 Jesuits were deployed to what was then called New France, now Canada and the eastern Great Lakes region of the United States. They were called “black robes” by native people because of the simple, functional cassocks Jesuits wore at that time, intended as signs of modesty and service.

Marquette was among them. Born near Laon, France, in 1637, he was cross-trained as a priest, mapmaker, navigator, and historian. Skilled at learning languages, he traveled to Quebec in 1666, where he mastered six Native American languages. Marquette and his colleagues are credited with founding the first European settlement in the Great Lakes Basin at Sault Ste. Marie in 1668. Three years later he established the Mission at St. Ignace, 60 miles south, which he came to regard as his home.

Like all social movements and the imperfect institutions that shape them, such initiatives inevitably leave mixed legacies: possible contributions but also ethnocentric bias, misplaced intentions, and masked self-interest. That said, there’s evidence that Marquette was someone who, though steeped in his own religious convictions and limited by them, was also empowered by those same beliefs to advocate for a deeper vision of shared values. He held strong opinions about the integrity of cultures, spirituality, and human dignity.

During the years Marquette canoed the waterways and traveled the forested trails of a new world, French and British fur industries were also establishing themselves as lucrative commercial enterprises in New France. High-profit, unregulated economic ventures among vulnerable indigenous communities usually bring trouble.

It’s no secret that native peoples were exploited and manipulated in many of the ensuing commercial transactions. Alcohol was often provided freely. Records show that fistfights and murders constellated around the interchanges between traders and native peoples. Jesuits, having taken vows of poverty, were sensitive about such issues. They frequently demanded that the native people they lived among be treated fairly. Many Jesuits, Marquette among them, were openly despised for this by traders and French government officials.

A little while before the private ceremony in the chapel, the delegation from Michigan gathers in the parking lot of the Ambassador, a historic, recently renovated hotel on the edge of Marquette University’s urban campus. We form a circle. Sage is lit. An eagle feather, its quill wrapped in leather, is passed around as delegation members smudge themselves, a traditional Native American custom to bring a blessing on the day.

At lunch in the president’s dining room, amid both formal and informal introductions, there is a subtle level of unease in the room as two worlds come together. Only university representatives speak. During the meal, a university staff member quietly moves from table to table distributing gift bags for the visitors: herbal teas grown in Wisconsin, hand sanitizer, a bar of gluten-free chocolate, and a coffee mug.

Shortly before leaving the dining area, a member of the St. Ignace delegation also moves from table to table, handing each university staff member a small twig of white cedar, carried from the shores of Lake Superior. “This comes from a tree along a far north shore where we know Marquette once traveled by canoe,” he says. “Cedar is one of the Ojibwa’s sacred medicines.”

Together we walk the few blocks to the chapel. When the private mass begins, three Jesuits lead the service, reading scripture, offering a brief homily, and celebrating the Eucharist. Half the gathered community participates. The university photographer moves among the small group snapping pictures, while two videographers from the St. Ignace delegation stand quietly along the walls.

Two boxes have been placed in front of the altar for the duration of the mass. An aged mahogany box from the university holding Jacques Marquette’s bones rests on a small table in front of the altar. Beneath it is a round, newly constructed birch-bark box carried here from Northern Michigan, prepared by one of the delegates from St. Ignace.

Following prayers, greetings are once again exchanged. Then nearly all the university staff members leave, and after some moments of transition, the chapel doors are closed once again. Anticipation fills the sanctuary. Time and space begin to shift. Chairs are rearranged in a circle, and ceremonial pipes are taken out of their carrying cases.

The smell of smoldering sweetgrass fills the room, blessing the chapel’s interior walls. A traditional smoking mixture called kinnikinnick (herbs, willow, bearberry) is passed around the circle. Each of us takes a pinch, holds it, then returns it in silence to a small wooden bowl. The kinnikinnick holds our prayers. It will be used in the sacred ceremonial pipes. An eagle feather is also passed around the circle, with each participant invited to share an opening thought.

The pipes are lit with sparks from flint and steel. A descendant of one of the oldest Native American families in St. Ignace rises. She opens the box of remains, which are preserved in small cardboard containers. Prayerfully, she transfers each carefully wrapped package of bones into the birch-bark box brought from St. Ignace. Prayers and smoke from the pipes float in the chapel’s air and settle over the bones.

Again the feather is passed. Everyone is given a chance to speak. The bones are blessed. A final prayer is lifted up in the Anishinaabe language. We rise from the circle. The doors of the chapel are opened to the fading light of a late afternoon. The journey back to Michigan is a seven-hour trip. It will be a long drive. A light rain is beginning to fall.

Beginning the walk back to the two pickup trucks waiting for us in the hotel’s parking lot, I turn and see two of my Native American friends pause briefly in front of the chapel doors. The sound of two eagle whistles echoes over the mist-covered garden and courtyard.

What is the history that has brought the remains of Jacques Marquette to this juncture? As with all narratives passed down over centuries, there are contested points of view. Are the remains authentic? What historical facts can be confirmed and what can’t? How much can we rely on the veracity of indigenous oral traditions? What competing, sometimes clashing, cultural perspectives come into play?

Two Jesuit historians, Al Fritsch and Joseph Donnelly, have researched and confirmed the following story, using Jesuit written reports from the 17th century, letters and journal entries from the 19th century, and indigenous oral traditions.

On a late afternoon in the spring of 1675, a lone birch-bark canoe with three travelers approached the mouth of a river on the shores of Lake Michigan, near what is now the town of Ludington, 90 miles south of the Straits of Mackinac. They landed their craft on a remote beach, built a small fire, then proceeded to construct a makeshift shelter for the night from branches and bark.

Two of the travelers are believed to have been of mixed tribal descent. The third was the Frenchman Marquette. That evening, after days of weakness and dysentery, the 37-year-old Jesuit priest died at the edge of the forest and water, surrounded by prayers from his two companions. The next morning, he was buried there. That place came to be known as the River of the Black Robe.

At the time of his death, Marquette, under request of the French government and with permission from his superiors, had recently completed mapping and exploring the Mississippi Valley with Louis Jolliet, a French-Canadian explorer from Quebec. That spring, Jolliet returned to Montreal. Marquette was on his way back to his home and the mission at St. Ignace.

The story now takes a fascinating turn. Two years later, in June 1677, members of the Native American community in St. Ignace traveled to his burial place. They retrieved his remains, cleansed the bones as was their tradition, and returned them by canoe north to the mission he had founded. Forty additional canoes of Huron, Ojibwa, Odawa, Potawatomi, and Iroquois tribal members accompanied the delegation as they landed at the bay in St. Ignace. Their faces were painted black in a custom of mourning.

On the Monday after Pentecost, Marquette was buried at his home beneath a simple altar in the mission chapel in St. Ignace. The service was framed by sounds of drums, prayers, and rituals of a traditional pipe ceremony.

Two hundred years passed. During that time, the mission was abandoned. The village of St. Ignace was repeatedly rebuilt and transformed. In 1877 Peter Grondin, a Native American employee of a local businessman, discovered the site of the abandoned mission during an unrelated excavation project. Under what remained of the altar’s foundation, he found a box of 19 bones, preserved in a double-walled birch-bark box.

What happened next remains a mystery. Somehow—and no story has been confirmed—the bones ended up at Marquette University in Milwaukee, though almost no one knew they were there. In 2018 a series of sensitive conversations began between the Native American people of St. Ignace and the university. Finally, the Museum of Ojibwa Culture in St. Ignace formally requested the bones, and the university accepted the request.

On June 18, Marquette will be reburied at the grave site where he was first laid to rest in St. Ignace in 1677. A circle has been completed.

But why would Native American people want to welcome back the remains of a zhaaganaash (Anishinaabe for “white man”), now that history has well documented the devastating results of missionary work, including the loss of indigenous culture and traditional beliefs, alongside the genocide of native peoples nationwide?

Francie (Moses) Wyers, cultural teacher for the Museum of Ojibwa Culture and a member of one of that community’s oldest Native families, responds, “I respect other opinions. But our own oral tradition has passed down the story, over hundreds of years, that Father Marquette was beloved by our tribal community. That he lived among us, shared our life together, respected our teachings. He cared for our people. He was one of us.”

Tony Grondin, a descendant of Peter Grondin, holds similar convictions. “Jacques Marquette was given, by my ancestors, the honor of being a sacred pipe carrier. For us, this is a sign of respect and honor. It means such a person shares our values, understands and respects our spiritual teachings. He lived among us. Showed kindness. Fought to protect our tribal communities. While being true to his own faith and mission, he honored and practiced many of our spiritual traditions. It was our tribal people who buried him 345 years ago.”

Marquette’s legacy continues to spark colliding points of view. He is regarded by many secular historians primarily as a French explorer who, along with Jolliet, mapped the Mississippi River. In portraits and paintings, he is often portrayed with minimal reference, if any, to his vocation as a Jesuit priest. The voices of Grondin and Wyers provide a different perspective that needs to be honored.

Shirley Sorrels, director of the Museum of Ojibwa Culture, is currently coordinating logistics for the upcoming reburial. “Our community is preparing with our Jesuit friends,” she says, “for a time of sacred ceremony and remembrance. Our intention is that it will be not only a cultural healing but a spiritual one.”

Marquette’s bones will be formally buried at his original grave site on June 18 by descendants of the Native American peoples among whom he lived. Representatives from Jewish, Buddhist, Christian, and the Three Fires (Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi) spiritual traditions will be present. On that day, the sound of eagle whistles will drift over the waters of the bay. Time will stop in St. Ignace.

Jacques Marquette is coming home.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Marquette’s bones.”