Embrace the new

The Marty male line since 1792 goes like this: Rudolph begat Bendicht begat Gottfried begat Emil begat Martin begat Joel begat Noah begat Muhammed. E-mail from Joel in Minnesota: “A Baby Boy! Muhammed Noah Marty! I’m so excited that I don’t even know if I have the spelling or weight facts completely straight, but here goes: After a very long day of labor, . . . they finally had to do a C-section. The baby was 7 lbs. 11 oz., 21 inches. Born in the first hour of November 21st, healthy and happy. Mom is doing fine . . . They are in the very room where Noah, his father, was born 21 years ago (less seven days); how the years fly by. I recall proudly calling so many of you that night like it was yesterday. I am so proud of Noah—who is bursting with pride, evidencing maturity and responsibility—that I too could burst, so I write to you all to share the good news. With love, Joel and Susie.” The Swiss/German and biblical naming finds prophetic complement, and Harriet and Marty become great-grandparents.

There must be a story. Of course, there is. Minneapolis has the nation’s largest Somalian community—part of the new-immigrant American mix that is transforming all our spaces and corners—and Noah married Sagal, from that community.

Forty years ago the marriage of a Protestant and a Catholic meant an epochal jolt for two families. Thirty years ago Jewish-Christian marriages caused upheaval. Both now are commonplace. Twenty years ago the influx of Asians and their presence in collegiate life led to many East-West marriages. Ten years ago we looked around and found that more marriages than not seem to involve gnostics and agnostics, indifferent and somewhat-different, nonobservant and semiobservant. Now, as the Muslim population surges, there are thousands of “my daughter-in-law is Muslim” stories, and they are soon to be taken for granted.

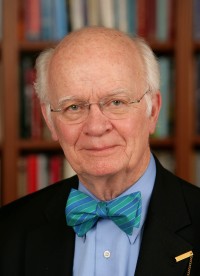

So we Martys join the adjusters, accommodators and welcomers. After all those years of talking about the “pluralist society” and about the wonders of meeting “the other”; of studying interreligious conflict and participating in interfaith dialogue; of chairing conferences on migration and refugees; of being committed to work on the religious dimensions of a “globalization ethic,” the realities have come close to home.

Theology rears its head, as well. When I am asked questions about “God and all the other people . . .” I tend to say “I don’t know.” Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger is sure: everyone but his people have “gravely deficient” faiths. I would use other language, never having been able to settle in to a simple, relaxed universalism, being a sort of evangelizer at heart who rejoices in the open embrace of Christ among all the peoples. These options are at war in the mind while the heart more simply reaches out.

The Lutheran in me for years has taken refuge in some lines of Luther, who, having spoken of how God conceals God’s self “in” revelation, suggested that there are things we do not know about God that are hidden “behind” revelation. So I picture the expansive love of God reaching beyond the circle of explicit Christians, even “anonymous” Christians, but I am not going to write a dogmatic dogmatics text on the theme.

For now I’ll keep the systematic theology questions in the back of my mind and do what thousands, millions, of families do: embrace the changes, embrace the new. When I first held and rocked my first great-grandson one November eve, I had only one thing in the front of my mind and heart: this is a beloved great-grandchild? Great!