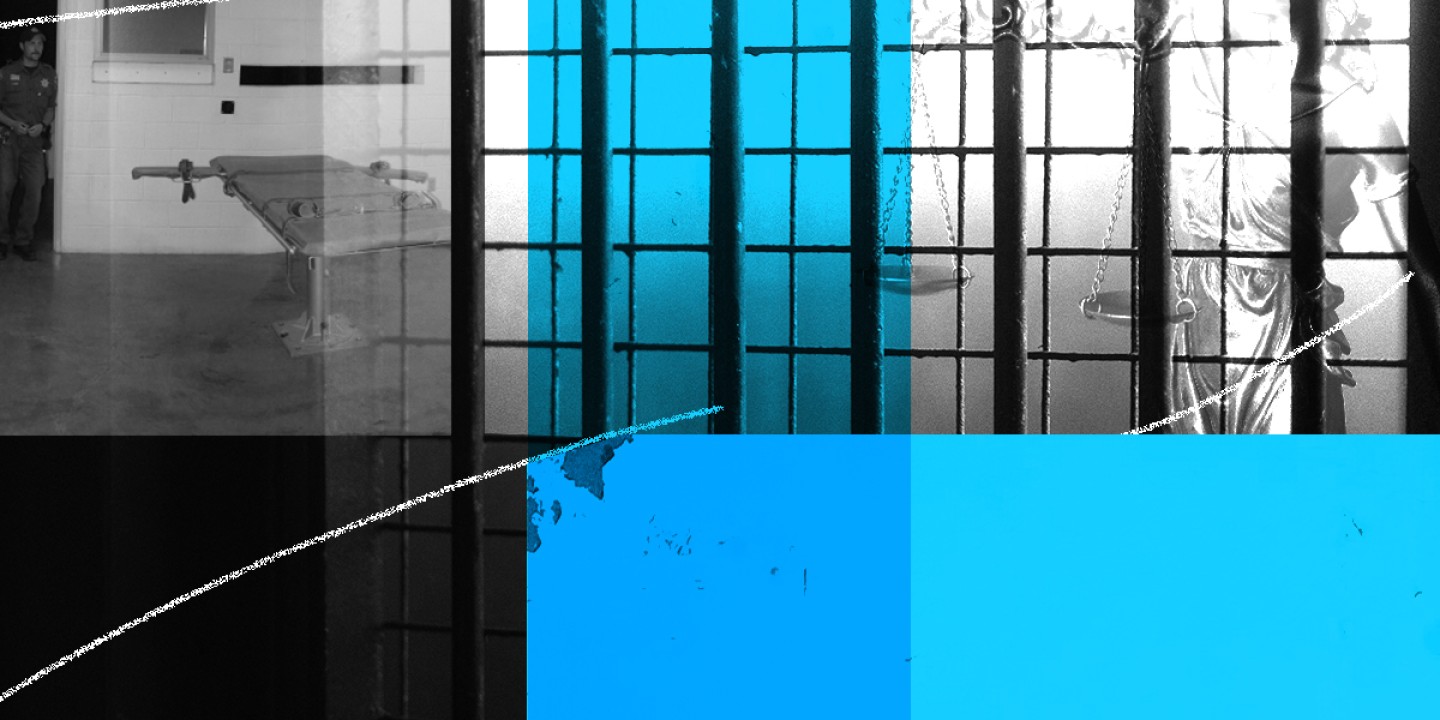

More than 100 faith leaders are trying to prevent Andre Thomas’s execution

Imagine what might happen if they poured that energy into abolishing the death penalty in Texas.

Occasionally a person on death row catches the attention of a large group of clergy. In February, more than 100 Texas faith leaders—Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, and Buddhist—signed a letter to the governor and the state board of parole and pardons, asking for clemency for Andre Thomas, who is scheduled to be executed on April 5. If the request is granted, they note, Thomas will be imprisoned for life without parole.

Thomas began hearing voices in his head at age nine. His family couldn’t afford mental health care, and as he grew up he self-medicated in unhealthy ways. After years of delusions and unhelpful encounters with the healthcare system, Thomas violently killed three family members who he believed to be demons. He went to prison, where he gouged out both of his eyes. His mental health has deteriorated so much over 19 years of incarceration that it’s unlikely he understands his situation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The faith leaders recount this history in their letter, and they name Texas’s systemic failure to provide treatment for low-income residents with mental illness. “Across our different faith traditions, we all believe in a just, merciful, and loving God,” they write, noting that Thomas was consistently denied the kind of help that may have prevented his crime—help that would have been just, merciful, and loving.

A public appeal for clemency is a clear moral good. This is especially obvious in the case of Thomas, whose situation is both extraordinary and tragic. What’s also true, though less obvious to some, is that no person should be executed by the government, whatever their crime and their particular circumstances.

Imagine what might happen if those 100 faith leaders were now to pour their energy into abolishing the death penalty in Texas. What if that many faith leaders in every state that still has the death penalty were to join the cause? The majority of death sentences in the US from 1976 to 2013 came from 2 percent of the nation’s counties, according to a study by the Death Penalty Information Center. What if faith leaders in the specific counties that hand down an exorbitant number of death sentences were to work toward unseating their local prosecutors in the next election?

A diverse group of faith leaders would undoubtedly make a variety of arguments against the death penalty. Some might appeal to principles of human dignity and mutuality, others to the conviction that we’re all sinners in equal need of mercy. Some might insist that it’s always sinful to harm a bearer of God’s image; others might articulate a moral calculus that deems an additional death’s costs greater than its benefits. Some might suggest that Christ’s death and resurrection reveals God’s desire to save us by restoring relationships rather than exacting vengeance (see “Restorative justice with Anselm,” p. 74). Some might look to sociological data, citing the death penalty’s ineffectiveness in deterring crime, its perpetuation of racial disparities, the arbitrary way it’s applied, its exorbitant cost, and its risk of killing innocent people.

All of them would be following the call of a God who is just, merciful, and loving.