The forced migration of Native Americans pushed them to inferior land

A recent study illuminates the economic cost of land theft. What might reparations look like?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 2018 that 25.4 percent of Indigenous Americans lived in poverty—a higher number than any other racial or ethnic group. Unemployment is persistently high among Indigenous people, particularly on reservations, where one-fifth of the US Indigenous population lives. While this inequity has many causes, a recent article published in Science magazine sheds light on one of them: the financial precarity caused by land dispossession due to forced migration.

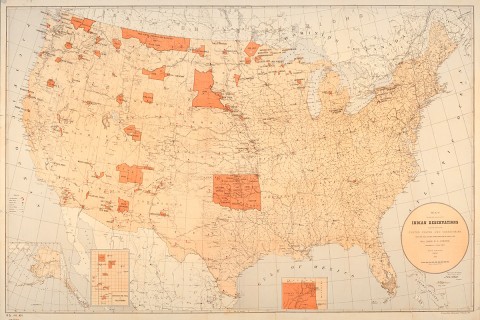

Researchers mapped the movements of 380 tribes over several centuries to compare historically Indigenous land with the land where reservations now exist. They assessed land quality using measures such as average rainfall, extreme heat and wildfire risk, mineral value potential, and agricultural suitability. Stark disparities emerged, confirming what some Indigenous people have long claimed: their reservations are on land that’s unable to sustain healthy life in an era of climate change. The authors conclude that their research illuminates “the factors that produced current inequities and future risks and should be especially useful for creating policies for restitution.”

What might such restitution look like? The growing popularity of land acknowledgments (e.g., “the Christian Century office is located on the traditional lands of the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Odawa people”) has raised awareness of the forced migration of Indigenous people, but such acknowledgments are rarely accompanied by any compensation for the land theft. Many homeowners know that their yards once belonged to Indigenous people, but few know what to do with that information given the reality that most of the United States sits on stolen land.