Rising up with Christ

In the Eastern church's art, Christ arises triumphantly and magnificently—but not alone.

As we waited to enter the Dark Church, a magnificent miniature Byzantine cathedral carved out of the volcanic rock of Cappadocia around 1050, we read the explanatory sign given in four languages. The English version noted that the church contained 15 frescos on the life of Christ, from Annunciation to Ascension. Instead of using the English word resurrection, the commentary used the Greek word anastasis. Ana/stasis literally means “up/rising.” It’s interesting to think of resurrection as an uprising. But an uprising by whom and with whom, we wondered; for what and against what? We also noticed that whereas the English version spoke of an ascent into heaven, the French, German, and Turkish versions spoke of a descent into Hades as part of the Anastasis/Resurrection scene.

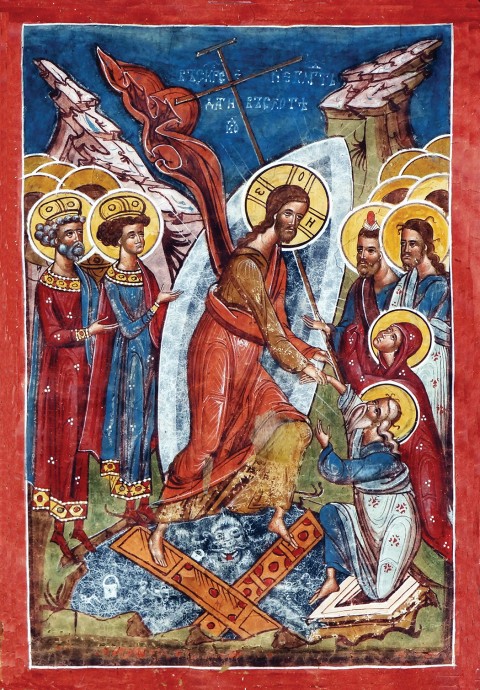

The central and tallest figure in the Dark Church’s Anastasis painting is Christ, identified by his cruciform halo, his name in the traditional two-letter (medieval) Greek abbreviations (IC XC), and the ceremonial cross in his left hand:

He strides forcefully to the viewer’s right but looks backward as his right hand firmly grasps the right wrist of a white-haired, white-bearded man identified as Adam. Behind Adam is Eve. Both Adam and Eve are being wrenched from a sepulcher. Behind them, the viewer glimpses the tops of six other heads, which are identified as belonging to the prophets. To the right are two figures, both crowned. One is older and bearded, the other younger and beardless. They are identified as David and Solomon.

It is what appears beneath Christ, however, that we found to be the most striking element in the entire fresco. Christ is emerging from a dark semicircular area below the ground, and he is standing atop or trampling down a full-bearded, prostrate figure whose feet and hands are chained. He looks up with frightened eyes at Christ, whose long cross seems to hold down his head. He lacks both halo and name. This is a Hades figure, personification of Death. He is also gatekeeper of Hades, the prison house of Death. To his right are scattered locks, bolts, and bars, originally part of a pair of bifold doors, which are flattened on the ground, arranged in a cruciform pattern.

Christ’s cruciform halo, his long ecclesiastical cross, and those crossed bifold gates form three deliberate connections between crucifixion and Anastasis—events in Christ’s life that are distinguishable but never separable, like two sides of the same coin. In terms of location, this image is not of hell but of Hades. In terms of personification, the image is not of Satan, the opponent of God, but of Hades, the custodian of the dead.

This resurrection-as-Anastasis depicts the crucified Christ breaking forcibly into Hades, tossing aside its bolts and locks, forming its gates into a cross, chaining the Hades persona, and liberating all of humanity—as personified in Adam and Eve—from the prison of death.

Seeing that image of Anastasis in Cappadocia led us to explore more deeply the Eastern church’s visual depictions of the resurrection. Over the next 15 years, we traveled across the lands of Eastern Christianity, from the Byzantine Tiber to the Syriac Tigris and from the Russian Neva to the Coptic Nile. As we traveled and photographed artwork, we noticed a pattern. We discovered that the Western church and the Eastern church have developed two different ways of depicting the resurrection, each involving its own iconography and its own theological vision.

The West celebrates the individual resurrection. Christ rises triumphantly and magnificently—but utterly alone. The guards of the tomb may be shown asleep or awake, but nobody else rises in, by, or with Christ:

Whatever may be implied about humanity’s future by this image of resurrection, it says nothing about humanity’s past.

The East, on the other hand, celebrates the universal resurrection. Here Christ also rises triumphantly and magnificently—but he takes all of humanity with him. Iconographically, paintings in the East show Christ grasping the wrist of Adam. By the year 1200, he is shown grasping both Adam and Eve. Anastasis-as-resurrection is the liberation of past, present, and future humanity from death in, by, and simultaneously with Christ.

Here, uniquely, Eve alone is grasped by Christ:

Which version is closer to the New Testament vision of Easter? This question is difficult to answer. In the Bible, there is no direct account of the resurrection. There are stories about the empty tomb and about Jesus appearing to his disciples, but there is no attempt to describe the actual moment of resurrection. As a result, Christians have had to imagine that moment. But what is striking is how two such profoundly different visions of resurrection could have evolved.

There are several indirect references to Christ’s resurrection in the New Testament. For example, Paul speaks of Christ as “the first fruits of those who have slept” (1 Cor. 15:20, which uses the same Greek expression as in Matt. 27:52). Is Paul imagining here an individual resurrection or a universal resurrection for Christ? To answer that question, we begin with the fact that whereas Paul’s pharisaic tradition imagined individual ascension for particularly holy individuals like Enoch, Moses, or Elijah, it never imagined resurrection as an individual event. Within biblical Judaism, resurrection was always corporate, communal, and universal. At its origins, the concept of resurrection—as distinct from ascension—involved the whole human race.

Further, in Romans 1:4, when Paul describes how Jesus “was declared to be Son of God with power,” he does not say it was “by his resurrection from the dead,” as the NRSV translation puts it, but rather “by the resurrection of the dead ones” (as in the Greek original: ex anastraseos nekron). Here, too, resurrection is intrinsically universal, as is God’s peace and reconciliation with humanity. It is past, present, and future.

One might argue that an individual resurrection is at least something that can be literally imaged as an event. Can we even imagine Christ arising universally as a literal event? In one sense, this question has driven the creative work of Eastern Christian artists and theologians through the centuries. But in another sense, the answer doesn’t matter, because universal Anastasis is not a literal vision; it is a metaphorical vision. And—at least for our species—metaphor creates reality.

But a question remains: For whom is Anastasis a reality-creating metaphor? Does it matter only for those who belong to a creedal church, or does it have meaning also in the public square? More bluntly, what does Anastasis have to do with humanity’s evolution?

As we’ve traveled and studied the Bible and early human civilizations, it’s become increasingly clear to us that the main problem from which humans need to be saved is escalatory violence. Anthropologists have shown that 5,000 years ago, on the Mesopotamian plains between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, at the dawn of civilization, the escalatory nature of human violence was already evident. It was, in fact, the midwife that rocked that cradle of civilization as the agricultural revolution of the Neolithic climaxed there. One can also see this intensification of violence in the biblical story, from Cain in Genesis 4:15 to Lamech in Genesis 4:24—including the inaugural mention of sin in Genesis 4:7.

Sociology has also uncovered the escalatory nature of human violence. Since Homo sapiens spread out from Africa 70,000 years ago, we have never invented weapons we did not use, nor created ones less lethal than those they replaced. We moved inexorably from iron sword to atomic bomb in about 3,000 years. As civilization’s drug of choice, intensifying violence deludes us into believing that peace on earth will result from global control, that nonviolence will finally derive from consummate violence.

If civilization saves us from barbarism, what saves us from civilization itself? This question is not just a moral or religious one but a historical and evolutionary challenge. Are we a magnificent but inevitably doomed species? Given our historic trajectory of escalatory violence, what can save our species from itself?

Very deliberately, Jesus of Nazareth lived by and died from incarnating one obvious answer—indeed, surely the only possible answer. Programmatic nonviolent resistance to violence alone can end civilization’s trajectory of escalation.

That Jesus’ personal vision and communal movement of the kingdom of God on earth embodied nonviolent resistance is certified historically by the mode of his Roman execution. When confronted with violent resistance, Roman rulers would crucify the leader and his closest supporters all together: “A man called Barabbas was in prison with the rebels who had committed murder during the insurrection” (Mark 15:7). When confronted with nonviolent resistance, however, Roman law decreed that “the authors of sedition and tumult, or those who stir up the people, shall, according to their rank, either be crucified, thrown to wild beasts, or deported to an island” (The Opinions of Julius Paulus Addressed to His Son).

Josephus and Tacitus agree that Pilate crucified Jesus, but neither mentions any arrest of Jesus’ closest companions. Furthermore, both Josephus and Tacitus find it necessary to explain why the execution of this leader did not destroy his nonviolent revolution. Pilate’s judgment was precisely correct—by Roman law. In the parabolic conversation between Pilate and Jesus in John’s Gospel, which contrasts Rome’s kingdom and God’s kingdom, it is clear that Jesus’ companions will never use violence, not even to save him from crucifixion (18:36).

The Anastasis vision of universal resurrection also points to the contrast between Rome’s kingdom of violence and Jesus’ kingdom of nonviolence. Eastern Anastasis art shows Jesus as indivisibly crucified-and-resurrected. His halo is imprinted with a cross, the gates of death are flattened in cruciform position, he bears wounds on hands and feet, and he carries a processional cross. The iconographic message is this: only nonviolent resistance to the violent normalcy of civilization can divert the human trajectory away from destruction and toward salvation on a transformed earth and within a transfigured world.

Given the violent world in which we live, then, universal Anastasis has everything to do with the public square. As human evolution plays out, Christ’s resurrection isn’t just a reality-creating metaphor for creedal Christians—it’s for all of humanity.

A version of this article appears in the January 31 print edition under the title “Rising up with Christ.” The first inline photo is by Sarah Sexton Crossan. The second and third inline photos are © Erich Lessing (Art Resource, NY).