The next monster

Stranger Things reassures us that the stories of the past can give us the courage to face whatever danger looms.

The 1980s were famous as the era of the missing child. The era was brutally announced when six-year-old Etan Patz went missing in 1979 from his home in lower Manhattan. In 1983, Adam, the TV movie detailing the abduction of Adam Walsh, captivated the nation when photos of 50 missing children were placed at the end credits. By 1984, photos of missing children had become ubiquitous on milk cartons, and Saturday morning cartoons built plotlines around stranger danger.

Stranger Things, the new Netflix show from Matt and Ross Duffer, takes us back into that era to explore the meaning of safety in both childhood and adulthood. It begins with the abduction of a boy named Will Byers by a monster that gained entrance to our world when a mysterious government experiment went wrong. The monster absconds with Will to the “upside-down world,” a place that resembles our own world but is filled with dangerous monsters and toxic air. Over the course of the season, Will’s friends and family slowly unravel the puzzle of his whereabouts and courageously enter government facilities and the upside-down world to save the missing child.

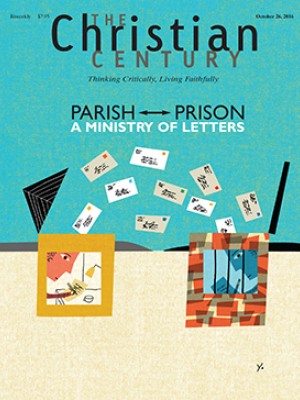

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Stranger Things is lovingly built from the reclaimed wood of ’80s movies like E.T., Carrie, The Thing, Firestarter, and A Nightmare on Elm Street. The Duffer brothers make no attempt to hide their inspiration. They are confident that those who weaned themselves on these films will understand the difference between theft and homage. The pop-culture pastiche—Dungeons and Dragons, Eggo waffles, Huffy bikes—helps build a story that taps into an anxiety that connects these stories of the past with our lives today. At its heart, Stranger Things is about the ways the fears of childhood turn into the anxieties of adulthood.

Three groups search for the abducted boy. Will’s friends are a tribe of D&D-playing nerds at the lowest rung of the elementary school food chain. Will’s older brother and his friend Nancy are a mismatched pair of ’80s teenagers—he’s a social misfit, while she’s a good girl in danger of making bad decisions. Finally, there’s Will’s mother and the local sheriff, who both struggle with the guilt of having failed to protect their children.

Within the three groups, anxieties about safety play out differently. The kids feel powerless in an uncertain world. Outside the basement where they play hours of Dungeons and Dragons, they are subject to the cruelty of their peers. But when they’re together, they conjure fantasies of power. Their strength is their loyalty to each other. Armed with newfound power to create and destroy, they must take on the burden of responsibility that comes with the power. Their impending adulthood is being formed in the crucible of real consequences. Prudence and recklessness are produced in equal measure. Meanwhile, the adults struggle with pain as they feel—and are—as powerless as their children.

Stranger Things reassures us that the stories of the past can help make a new generation ready to meet new monsters. Retelling old stories gives us courage for the next confrontation and empowers us to travel into upside-down lands and retrieve what is good, no matter what danger looms. In the ’80s we feared that children would be snatched by predators; today we fear they will be snatched by addiction. In Stranger Things, Will is taken to a toxic upside-down world; today we wonder if that toxic world is social media.

By the end of the first season of Stranger Things, the adults gain entrance to the upside-down world. Their rescue mission is a desperate act of love. In what often seems like a fool’s errand, they break down the doors of hell, retrieve what has been taken, and right the wrongs of monsters. In other words, they descend into hell, gather what was thought dead, and set it free. It’s a pretty good story, one worth telling to our kids—and ourselves.

A version of this article appears in the October 26 print edition under the title “The monster next door.”