A church for the kids: Why I still care about denominational politics

Denominational meetings can be difficult. My Sunday school class reminds me what's at stake.

We knew this was an important denominational meeting. We had each prepared by reading our dockets of background information and position papers. We had met with church leaders in our regional conferences. And we had prayed regularly for the leading of the Holy Spirit—that God would open us to her counsel.

Now the 20 of us—representatives from all parts of our church—sat around a table listening and arguing, trying to discern together a faithful decision for all our congregations across the nation. We voted on the status of LGBTQ pastors in our denomination, on whether we would recognize them as true ministers of God.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Sitting in those boardrooms—my head echoing with the voices of our constituencies, my mind recalling all the relevant theological arguments—I would remind myself why I was there. I remembered what I was supposed to be doing with the power delegated to me. I thought about Sundays at my church, the hour before worship begins, when I join the kids to sing about God. We shout out lyrics about Abraham and Sarah, about being children of God; we dance around the front of the sanctuary, sticking out our arms and legs, twisting and turning: “Right arm, left arm, right leg, left leg, nod your head, turn around, sit down!”

I did the work for them—for our children, for their church. I participated in conference calls and denominational meetings, I wrote reports and argued with other leaders, all in order to help build their spiritual home: a church where they will find God’s love and God’s embrace of their lives.

A few months ago, on the Sunday when we remember the baptism of Jesus, one child told me about this new thing she was doing with her mom that day: a trust fall. As she explained the excitement and scariness of it, I decided that we would spend our Sunday school hour doing trust falls as a way to explain what Jesus did when he was dunked into the Jordan River, and what we are doing when we let our church baptize us. They took turns, one after another, letting themselves fall backward into the arms of the rest of us in the class. This, I told them, is what it means to be baptized—to let ourselves fall into the mysterious love of God by trusting the people at church to catch and hold us, knowing that they will be there to offer God’s care for our lives.

In a room with other church leaders, discerning policies to guide our denomination, I would think of the children in my Sunday school class. I thought of what it means for our church—our congregations and our denomination—to be a safe place for them to explore the mysteries of God, a healthy place for them to learn who God created them to be. “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them,” says Jesus, “for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.” If heaven belongs to the children, then our church should, too.

When I think of my Sunday school children, church politics gets personal. I want a church that is for them, for all of them, even the kids who will find out that they are LGBTQ. I want them to know that God made them the way they are, that God’s love is in the way they love—that God didn’t make a mistake.

I want them to know along the way—week after week, year after year—that they will always be welcomed to speak a word of good news from the pulpit and to take a turn providing child care in the nursery, that they will be able to serve communion and chair committee meetings. I want them to know that I will be thrilled when they tell me about falling in love, and when they ask me marry them—that on their wedding day I will be up there holding back tears as I pronounce them husband and husband, wife and wife, and letting the world know that God blesses their union, that God loves them.

I’m 36 years old, and I’ve been a pastor for a decade. I was given more power in denominational leadership roles than I was prepared for. I had to learn along the way—from people who shared their wisdom with me, mentors who believed in me and trusted me.

I know I disappointed many of them because I can’t go along with long-standing traditions that put restrictions on LGBTQ members in our churches. Nor can I wait for the next generation to change our policies, because I’ve sat with people who have shared their pain with me—their spirits wounded from years of being told that God made a mistake in creating them to love who they love. I want a church where people don’t grow up to hate themselves because of their sexual desire, their desire for love.

I love the kids at my church. My votes, my engagement in church politics, have been for them. I’m on their side. I want a church that wants them, and I don’t want them ever to doubt that. When they grow up and move on, I want them to remember that I love them, that I have always been there to reassure them of God’s love.

Denominational leadership is complicated. Bureaucracies are labyrinths. I’ve been at the table when we’ve made decisions that would hurt people I love, decisions that hurt people in my congregation. What guided me through the haze of decision making was one question, a voice always in my head: Who are you for?

After returning home from a board meeting, with the deliberations echoing in my mind, I would find all the assurances I needed by going to Sunday school and helping our children carve blocks of wood into nativity characters, or build the Temple with Legos, or pray the Psalms by coloring their feelings onto paper. These are the people I thought about each time I argued for a policy change, each time I put my hand up to vote for a future that has not yet come.

Who are you for? If you want my answer, you’re welcome to join the kids in my class on Sunday. Perhaps they’d even let you try a trust fall—falling backward into their arms, surrendering your vision for church to them.

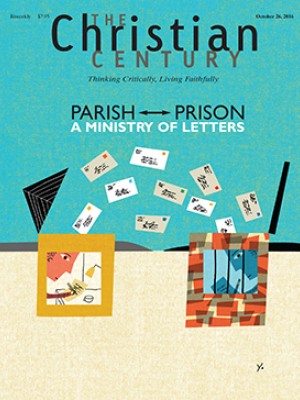

A version of this article appears in the October 26 print edition under the title “A church for the kids.”