Faith in translation: The gospel as a second language

I recently moved from Chicago to Birmingham, England, after my spouse got a job here. Since then, I’ve been regularly embarrassing myself during simple acts of conversation. I’ll make an earnest comment—such as saying “Wow, I’m stuffed!” at the end of a dinner party—and be met with unexpected silence, disgust, or laughter. It’s often said that the United States and the United Kingdom are separated by a common language. A standard phrase on one side of the Atlantic might make no sense at all on the other—or it might make a totally different impression from the one intended. I find myself constantly trying to translate between one version of English and the other.

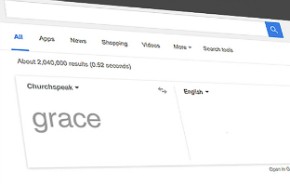

I’ve also been visiting a lot of churches. I’m searching for a community of people to share life with; I also have a professional interest as a minister, church planter (in the United Kingdom, a “pioneer”), and ministry coach. One thing I’ve been struck with in many of the places I’ve visited—from High Church establishments to evangelical church plants to Pentecostal prayer meetings to fringe missional collectives—is how thoroughly their liturgical words and practices assume that Christianity is the first language of the people gathered there. Words like sin, grace, gospel, atonement, salvation, offering, tithe, and communion are mostly used without being defined or interpreted. (This is certainly not a situation unique to England.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

To be sure, many such words are particularly beautiful and beautifully particular. Few synonyms could adequately convey their richness. So don’t get me wrong: I don’t believe that we should jettison our ancient vocabulary. Instead, we should teach it compellingly and as early as possible. When it comes to learning languages, children have a tremendous advantage. After puberty, both the brain’s plasticity to internalize new constructions and the mouth’s flexibility to make new sounds begin to diminish. Likewise, it’s important to learn Christianity early, as a first language.

Some parents make the conscious choice not to raise their children in a faith community, so that when they’re older they can make their own religious choices. When parents tell me they’re considering this, I challenge them to instead give their children a deeply rooted spiritual communication system that they will be able to employ intuitively throughout their lives. If at some point their children want to abandon this first language or to learn a second, they can still make that choice. (Interestingly, linguists say that knowing a first language really well—how it’s structured and how it works—makes it much easier to learn a second language later in life.) But the risk of waiting until some future age when they can “decide for themselves” is that they won’t learn any faith language at all.

Indeed, a fast-growing number of people do not have a religious first language. And many churches don’t seem eager to learn how to connect with them—how to teach Christianity as a second language as well as a first.

What does it take to accept this task and to learn to translate Christianity into the secular vernacular? Without doing this, it’s hard to engage those who are investigating spirituality and faith with no prior religious language or experience. Engaging them requires, at the most basic level, the capacity to communicate effectively.

Teaching Christianity as a second language will require developing the capacity of individuals and congregations to say something about the gospel. For most of us this will probably mean learning how to say something about our own experience of the gospel. This may be why some Christianity-as-first-language speakers are reluctant to embrace this ministry of translation: it might require them to testify, in descriptive and narrative language, to what it feels like to undergo the gospel in their own skin. For many Christians, this is awkward territory.

In fact, some of us find the prospect of personal testimony so uncomfortable that we have defaulted almost completely to nonverbal forms of evangelism. As long as we don’t have to actually say anything about God, we’re OK. We’ve heard sermon after sermon, usually from first-language speakers, on that old chestnut misattributed to St. Francis: “Preach the gospel at all times; when necessary, use words.” It’s a lovely line, and of course we should be concerned with letting the gospel permeate all of our affairs. But in this day and age, especially when it comes to ministry with the next generations, words will be necessary much of the time. Quoting St. Francis to avoid having to find words doesn’t just suggest a failure of nerve and a lack of verve. It can also be a kind of first-language privilege.

As Tim Keller points out, nearly every time the word euangelion appears in the New Testament, it’s connected to a verbal expression of the good news. The gospel must be “en-worded,” and not only that: it must be translated into a language that makes sense to hearers who don’t speak Christianity.

How can we practice our language skills? In many contexts, corporate worship remains a primary gathering for Christians. So it’s a good place to work on shifting congregational culture toward a ministry of translation.

One way to do this is to fold into worship some descriptions—carefully crafted but not pedantic—of different elements of the service. Along with helping people who are just learning the language of Christianity, this can be valuable to those who have been sitting in the pews for years using language they don’t really understand. Another strategy is to try to hold together didactic and narrative preaching traditions. We can dive deeply into ideas, refusing to dumb them down—while also approaching them narratively, as Jesus did, weaving in human stories and pointing frequently to worldly things.

Perhaps most important is recovering the practice of lay testimony. When it comes to starting and revitalizing churches, there are few panaceas—but for my money, this is one of them. Each week, a different layperson might be invited to stand up for five minutes and share how God is moving (or not moving) in their life. True, unvarnished stories are best—as Proverbs 14:25 says, a truthful witness saves lives.

One helpful exercise for Christianity-as-first-language speakers is to translate the word gospel into ten or 12 words of compelling, strictly secular language. Another is to follow the example of Alcoholics Anonymous—a group that is excellent at translation—and break down salvation into a series of three to five steps, again using compelling secular language.

The church includes first- and second-language speakers, with a myriad of gorgeous accents. Let’s practice together, all testifying to what it’s like to encounter God.