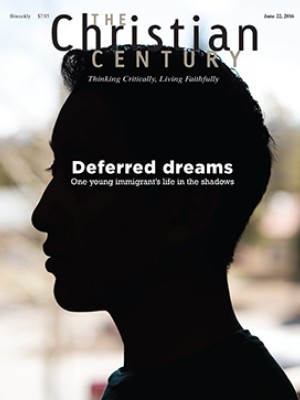

"My mom agreed to using my whole name,” Brayhan Reveles tells me. The question of whether I could use it had loomed over us since I first started talking to Brayhan about his immigration status.

Brayhan is a high school sophomore and one of the 665,000 immigrants who arrived in the United States as children and now have temporary legal standing under President Obama’s executive order known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

According to a study by the Center for Migration Studies, 85 percent of DACA recipients grew up in this country and more than 90 percent have already graduated from high school here. Ninety-one percent speak English fluently or exclusively. They have family ties and school and work histories in this country, and their plans for the future—for going to college and starting careers or families—begin and end in the United States. But they have only a fragile legal footing here.

Brayhan’s mother, Cristina, heard about my interest in talking to DACA recipients through a mutual friend. At first Cristina wanted nothing to do with me, and I understood: Why should she risk exposing her family? But then a leading presidential candidate said that Mexico was sending “people who have lots of problems” to the United States and that immigrants were bringing drugs and crime with them and were “rapists.” I soon got a call from my friend, who said, “Cristina would like to talk to you.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“Why did she change her mind?”

“Donald Trump.”

President Obama issued DACA in 2012 only after legislation known as the DREAM Act failed in the U.S. Senate by five votes. The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act was designed to provide a path to citizenship for young immigrants who did not have documents but had been in the United States since childhood.

After the bill failed in 2010, the young immigrants who had lobbied for the bill, so-called dreamers, pressured Obama to take unilateral action. When Obama attempted to explain to the National Council of La Raza in spring 2011 why he could not bypass Congress, young activists shouted back, “Yes, you can! Yes, you can!” A year later, Obama announced DACA.

Critics called DACA an “illegal amnesty” program and accused Obama of overstepping his authority. Some governors threatened to sue.

Following the outlines of the DREAM Act, DACA allows undocumented immigrants who arrived before their 16th birthday and who have lived continuously in the United States since June 15, 2007, to stay and work for two years. The two years can be extended for another two years. Recipients must not have not committed any crimes and must prove their long-term residency in the United States. They also must be currently enrolled in school or have obtained a high school diploma or served in the military.

Despite young people’s lobbying for DACA, no one knew how many would sign up for the program, since enrollment entailed risk: immigrants would have to give personal information to the very same government agency that could deport them and from which their families had been hiding all their lives. To the surprise of some organizers, young people came out in huge numbers. In August 2012, for example, when the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights announced an event that would help young immigrants apply for DACA, 2,200 people were standing in line by 7 a.m. Organizers estimated that 13,000 had arrived by 1 p.m. The response around the rest of the country was just as striking.

Officials estimate that 61 percent of those eligible for DACA have enrolled. Many of the remaining 39 percent may be young parents, says Hirokazu Yoshikawa, professor of globalization and education at New York University. Older dreamers may feel especially distrustful of the government and most concerned about keeping their families intact. Others may have committed petty crimes as children and are waiting for their records to be cleared.

Among the benefits of DACA is that people can travel to their countries of origin to visit their families. In many states, DACA recipients can also receive in-state tuition for college, go on study abroad trips, apply for driver’s licenses, and get jobs that could eventually lead to an opportunity for permanent residency status. DACA is not by any means, however, a solution to the immigration crisis. It does not provide a path to citizenship.

Before I talked to Brayhan, I met with Cristina at her apartment one afternoon before her children came home from school. Although the outside of the building where she lives was dilapidated, the inside of the apartment was large and carefully decorated. School photos of her children stood on the shelves of the entertainment center along with shots of herself with her husband on vacation. Everything had a feeling of permanence and care. A little dog she alternately called “Darwin” and “Camilo” ran back and forth between the dining room and the living room.

She told me about her decision as a young woman of 20 to come to the United States with her husband and Brayhan, who was then a baby. “I did not like the culture that some of the families in Mexico had—where the husband worked here, and they saw him just once a year. I needed to raise my children together with my husband.”

During the 15 years that they’ve lived in the United States, the family’s status has been a kind of open secret. When Brayhan was in preschool, Cristina enrolled in a leadership program for Latinas run through Head Start. She successfully advocated for new bus routes that would give every child in the school district access to transportation. She recently helped organize a leadership training institute for immigrants. She’s charismatic and smart, and people constantly suggest jobs she might take. Recently someone asked her to run for the school board. It frustrates her to turn down such opportunities.

“I don’t want to waste my life,” she said. “But sometimes I feel like a pretty bird in a cage who picks up scraps and tries to make the cage more beautiful.”

She has carefully guarded the knowledge of Brayhan’s legal status. Few people outside the family know that Brayhan is not a citizen. When he was invited to join an elite ski team, she hesitated to give permission because the registration form had a space for a Social Security number. At first she told him he couldn’t ski, and then she changed her mind. But it bothered her to leave the space for the Social Security number blank.

As for Brayhan, he has thrived in this country. He gave the graduation speech for his eighth grade class, after which the high school principal said, “Brayhan, you will be president of the United States someday.” He smiled and said thank you, feeling awkward that the principal didn’t know about his undocumented status. Later he told his mother, “I know I can’t be president. But maybe governor or a senator.”

This confidence may be the greatest gift his mother has given him. He plans to earn a high school diploma simultaneously with an associate’s degree at the community college and then enroll in a four-year university to study mechanical engineering, business, and politics. When Cristina’s English-speaking friends talk about Brayhan’s college prospects, they tell her, “Don’t aim too small. Think Harvard.”

Cristina appreciates their accolades, but she worries: What if all of his dreams end in disappointment? What if all her encouragement only ends up breaking his heart? “I keep thinking, ‘I will find a way for him.’”

Brayhan’s confidence is evident in his bright green Converse high-top sneakers, his unusual sunglasses, and his red watch that beeps on the hour. When he took part in an environmental project, a leader asked students to talk about the first two weeks of the team’s work. “Do you want to submit your thoughts anonymously?” she asked. “Or read them out?”

“Read them out,” Brayhan offered. He looked around. “I mean, I don’t want to speak for anyone else, but I think we would be comfortable reading them out.”

Like most high school students, Brayhan wants a driver’s license and a job. Both desires present dilemmas for his parents. If they go to the local office of motor vehicles, will the person behind the desk learn about Brayhan’s status? Should they do it anyway, or go to another county, or just tell Brayhan that the risk is too great?

Brayhan is constantly caught between what is normal for a teenager to do and what his legal status does or does not allow. No decision is simple. But Brayhan is not content to remain hidden. Before working on the environmental project, his previous community service was as a leader in an organization called Student Voice.

Cristina is torn. She is proud of Brayhan’s work and high profile in the community but uncertain about what this visibility might cost him. Her husband worries even more than she does. Fernando, whose job in construction has supported the family, told Brayhan, “Don’t do that youth researcher position. Don’t go skiing. Why are you doing a sport that is not yours? You will go back to Mexico and then what will you do? This is not your community.”

But Cristina sees how her husband’s perspective limits Brayhan. “Brayhan says he wants to fly high,” she said. Yet without documents, “our world is very small,” she acknowledged. She looked around the room. She knows firsthand what it means to say no to opportunities. The personal cost is high. “My world is small now, but I will try to make a pretty world anyway,” she said.

Cristina and her husband applied for DACA for Brayhan in the summer of 2015, when he was 15. The preschool had lost the records that could prove how long he had lived here, but the lawyer said that records from kindergarten were fine. Brayhan now has numbers that he can put at the top of registration forms, and Cristina thinks that helps him psychologically as well as practically.

“Now he will feel more comfortable going for financial help. Maybe that number will help him fill out applications. I think it was a gift for all the students. They can feel less pointed at. If someone asks for a number, they can give a number.”

The Obama administration was encouraged enough by the response to DACA to attempt expanding it in 2014. It proposed adding one year to each of the DACA recipients’ periods of relief (for a total of six years instead of four) and enacting a program called DAPA (Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents), which would give the parents of DACA recipients the same status as their children. The potential pool of beneficiaries would expand to an estimated 5 million people.

Within hours of Obama’s announcement of that plan, Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County, Arizona—a close ally of Donald Trump—challenged the executive order in federal court. Governors from 26 states filed a similar case in a Texas federal court. Arpaio’s case was dismissed, but the Texas federal court blocked both the expansion of DACA and the introduction of DAPA. The Justice Department asked the Supreme Court to review this decision. The court heard the case in April, and a decision is expected this month.

Should the Supreme Court decide that the executive order did indeed exceed the president’s authority or should justices split 4-4, the future of DACA is threatened. Stephen Yale-Loehr, professor of immigration studies at Cornell University, says that a court decision against the expansion of DACA (or one that reverts to the lower court’s decision on the question) is not good news for the original DACA. The president can continue it, but once it has expired, it is unlikely to be renewed.

Yale-Loehr says the future of people like Brayhan is “perilous.” He does not think that the resources of the Department of Homeland Security will be used to round up and deport DACA recipients, but young people would return to the same situation they were in before the executive action, in which they have no legal path for staying in the only country they know.

Even more crucial to the future of DACA recipients is the presidential election, which has become a referendum on immigration. Arpaio, in endorsing Trump in January, said, “I have fought on the front lines to prevent illegal immigration. I know Donald Trump will stand with me and countless Americans to secure our border.” At his rallies, Trump always mentions restriction on immigration and those lines win the loudest applause. Extreme limits on immigration is a central tenant of his political platform.

Fiercely attuned to what happens next in the election, Cristina listens to Spanish language news and scans Facebook for political commentary. She was startled when an undocumented immigrant in a nearby community was pulled from his truck and beaten. The rise of Trump has her wondering if maybe her family should go back to Mexico. “He is awakening racism in those who don’t have understanding,” she says. She worries that the opportunities DACA created will evaporate and a culture of fear will take over.

“American society is losing a lot of talent,” she says. “I feel that the young people are frustrated because they can’t move forward; they are in limbo. They can’t establish their lives and their work. There are so many who are so talented. I don’t understand why a society would deprive itself of so many children with such ability.”

After school one day, Brayhan and his mother sit at the kitchen table and look through scholarship applications in a thick black binder provided by the high school’s precollegiate program. Again and again they encounter the warning “U.S. citizens only.” They turn the page and read about the next school. Cristina tells me, “I want people to know how difficult it is to achieve goals when you are in this situation.”

Brayhan will apply this spring for his two-year renewal of DACA. Next fall, he will spend a semester at a private school for outdoor leadership. He isn’t concerned that putting himself forward could land him in trouble down the road—but his parents are. “We don’t want to lose what we’ve already gained,” Cristina says.

Brayhan is focused on the immediate future. When he has used up the four years of DACA status, he will be 18 and likely have a high school diploma and a two-year college degree.

Looking over the packages of information sent by colleges, Brayhan tells me that some schools are too focused on grades. “Grades are a really superficial way to understand if a person will be successful. I read a study that showed that the character of a person is much more important. I keep my grades up and work hard to create a lasting impact, but there is much more to a person than a piece of paper that classifies you. Character and actions make you who you are no matter where you come from.”