The other Jerusalem: Poverty and isolation in Arab neighborhoods

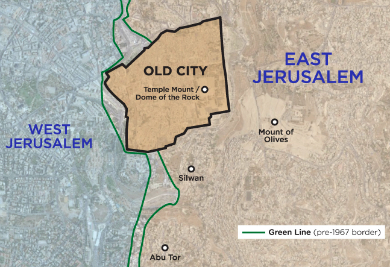

Some months before the recent outbreak of violence in Jerusalem, I drove from my home in a western suburb of Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives on the eastern side of the city. My route took me through the Arab neighborhood of Abu Tor. Compared to the shiny new suburb I live in, it seemed a different world. The roads were marked by potholes, and the miserable-looking stores were squashed between residential buildings badly in need of repair.

The sharp contrast between West Jerusalem and mostly Arab East Jerusalem reflects a political, cultural, and economic divide. It is along this divide that much of the violence of recent weeks has erupted, leaving 20 Israelis and over 100 Palestinians dead.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The rest of the world does not recognize Israel’s sovereignty over East Jerusalem, which Israel captured in the 1967 war, but Israel claims all of Jerusalem as de facto and de jure under its control. However, neither Israel nor the Jerusalem municipality has invested the kind of resources in the eastern part of the city that would make its inhabitants feel like full citizens.

Of Jerusalem’s 830,000 residents, 302,000, or about 37 percent, are Arabs, and most live in East Jerusalem. This is the largest concentration of Arabs in Israel. Of these residents, some 75 percent live below the poverty line, and 84 percent of those are children. (The comparable figures for the Jewish population: 22 percent live under the poverty line, of which 31 percent are children.) The Israeli-built separation barrier (it is mostly a wall in Jerusalem, in other places a fence) cuts off about 80,000 of these Arab residents from the municipality. The wall also cuts off other Arabs in the city from their fellow Palestinians in the West Bank

Though Arabs are 37 percent of the city’s population, they receive between 10 and 15 percent of the municipal budget. East Jerusalem has almost no parks and few community centers, after-school activities, or welfare clinics. The eastern side lacks sewage pipes, and parts of it are used as waste dumps.

Though Arabs of East Jerusalem pay taxes, they are disempowered politically—partly by their own choice. Arab citizens who fall into the category of permanent residents of the city can vote in city elections and even run for a seat in Israel’s Knesset, but most decline this opportunity, since to do so would be to tacitly acknowledge Israel’s claim to the entire city. Palestinians’ deliberate nonparticipation ensures that decisions regarding East Jerusalem are made without their consent.

City officials have made only meager investments in education in East Jerusalem. The city built about 200 new classrooms in the area between 2009 and 2014 and has plans for another 211. That would still leave the need for a thousand more classrooms.

Arab schools in this part of the city exhibit a high dropout rate—26 percent of students drop out in the 11th grade and 33 percent in the 12th. The recent violence tells us what these dropouts may be doing with their free time.

Some 20,000 houses in East Jerusalem lack permits and are therefore subject to demolition by Israeli authorities. There is a Kafkaesque reason for the Palestinians’ lack of housing permits: permits are given only when a master housing plan for the region is in effect, and no such plan has ever been developed for East Jerusalem.

Given all these realities, the question arises as to why the Palestinians don’t protest more than they do. One reason is that much of the Arab population is economically tied to West Jerusalem. Over 35,000 (perhaps as many as 50,000) East Jerusalemites work in the western part of the city, whether as doctors, nurses, pharmacists, gas station attendants, or garbage collectors. People who have a job and want to hold on to it are less inclined than teenagers are to pick up a rock or a knife.

Unemployment statistics for East Jerusalem are wildly fluctuating and unreliable. Figures are given from 9 percent to 40 percent for the men. As for women, the figure of 85 percent “unemployed” is merely extrapolated from the more reliable figure that 15 percent of women work, but that does not mean of course that the rest are unemployed. Many of the women choose not to work. Theirs is a traditional community in which women look after the home and family.

“Palestinian kids in East Jerusalem know they have no future, nothing to look forward to,” observed Daniel Seidemann, an Israeli lawyer and expert on Jerusalem politics, who recently wrote a book about the city, A Geopolitical Atlas of Contemporary Jerusalem. “This is a population adrift.”

Seidemann is surprised at how many of the people leading clashes with police have been women. “This is quite radical,” he told me. “You have a patriarchal society, and yet there are two uprisings, one by the youth and the other by women. To a certain extent this is a vote of no confidence in the local households, the economic dimension being a major factor, in that the men don’t have jobs or economic power.”

For Seidemann, the situation can be summarized briefly: “The Israeli condition is one of denial, the Palestinian condition is one of despair and clinical depression.”

Jerusalem has witnessed the slow disappearance of Christians. From being 20 percent of the city’s population in 1948, Christians are now a mere 2 percent, or about 15,000, of whom 12,000 are Palestinians. Many of the rest are church officials or members of monastic orders. The migration of Christians has siphoned off many of the educated and wealthier Palestinians who might have engaged Israeli authorities in meaningful negotiation.

The politics of East Jerusalem is also shaped by archaeological work aimed at demonstrating Jews’ historical connection to the area. These digs also serve as a vehicle for Jewish expansion into Arab neighborhoods. Much of the work is financed by private companies, a fact that allows the government to avoid taking responsibility for it. The Ir David (“City of David”) Foundation, commonly known as El-Ad, is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation and development of what is claimed to be the original location of David’s city near the predominantly Arab neighborhood of Silwan. David Shulman, a professor at Hebrew University, contends that the archaeologists have “sold out to people with money” in order to pursue these excavations. “There is a clear political agenda around this site, and they’re lending their name to it. It’s shameful.”

El-Ad and other groups take over Arab-owned properties. They expropriate them for security reasons, requisition the properties of absentee owners, or contend that a particular site is legitimately owned by Jews. Such efforts have not noticeably increased the Jewish population in East Jerusalem, but they have exacerbated tensions.

|

Another major source of tension concerns the fate of the Temple Mount, what Muslims call the Noble Sanctuary, the historic site of the destroyed Jewish Temple and home to the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock, where Muslims believe the Prophet Mohammad ascended to heaven.

After capturing the site in the 1967 war, Israel allowed control of the Temple Mount to remain with the Waqf, a Muslim trust. Israel allows Jews (and Christians) to visit the site, but not to worship or pray. Only Muslims are free to pray on the Mount. In recent years, however, various Israeli extremists have called for the right to worship on the Mount, and some have even called for a rebuilding of the Temple. The Israeli government has denied having plans to change the status quo, but its statements have not convinced all Palestinians.

Meanwhile, some Palestinians have spuriously argued that Jews have no connection to the site and that the Temple is a Jewish myth. This assertion goes against Muslim tradition itself, which says the site is sacred because of Solomon’s Temple. Muslims also broke an unwritten agreement in the late 1990s when they built a huge underground mosque under the Temple Mount. Extremism on the one side generates extremism on the other.

But the two sides are not equal, said Shulman. “There’s a vast asymmetry built into the situation. Two-thirds of the Arabs are in favor of some type of solution. All the research shows this. The Fatah leadership, with all its faults, is people with whom you could make a deal. . . . The deep core of the problem is that people like Netanyahu are not interested in anything other than taking as much territory as possible. That’s the nature of occupation.”

In the wake of the recent violence, the Israelis and the Jordanians agreed to install cameras on the Temple Mount to prove that the status quo has not changed. The problem with this move is that it is the Waqf, not Jordan, that handles the day-to-day events at the site. The Waqf is officially a committee appointed by Jordan, as the custodians of the Temple Mount, to guard over the site. But the Jerusalem Waqf, made up of senior Muslim clerics, often acts as if it is an independent body.

The just-released documentary film One Rock, Three Religions contains footage of Pope Francis calling for tolerance and coexistence in Jerusalem. Another observation made in the film is perhaps no less important. An Arab doctor says of his young son: “He’s not interested in the Temple Mount; he and his friends want a swimming pool and parks that they can play in.” If the politicians and religious leaders could understand that fact, perhaps the situation would be different.

The tensions in Jerusalem are ultimately rooted in the deep frustration that any subjugated community would feel in this situation. That situation is made more complex by the surrounding political environment that continues to threaten Israel’s existence. The so-called Arab Spring has led to instability across the region, aggravated by the rise of ISIS and the increased power of the terrorist group Hezbollah. This lack of stability is often used by Israeli governments as a reason to do nothing. But a lot could be done, even under current conditions, to alleviate the real problems of East Jerusalem.

This article was edited on January 20, 2016, to correct the name of Daniel Seidemann's book. It was previously cited with the name of the publisher, Terrestrial Jerusalem.