Dance in the dark: Preaching the blues without despair

In his song “Call It Stormy Monday,” T-Bone Walker laments how bad and sad each day of the week is. But when he gets to Sunday he says, “Sunday I go to church, then I kneel down and pray.”

Walker’s song unintentionally lifts up the challenge that the blues placed before the church and that black religiosity still seeks to solve. “Stormy Monday” forces the listener to reject traditional notions of sacred and secular by connecting the pain of the week to the sacred service of Sunday. For Walker there is no strict line of demarcation between the existential weariness of a disenfranchised person of color and the sacred disciplines of prayer, worship, and service.

We must understand this connection if we are to reclaim the best of the preaching tradition. We must learn what I call the Blue Note gospel. If we are to get to our resurrection shout, we must pass by the challenge and pain called Calvary.

But what is this thing called the blues? It is the roux of black speech, the backbeat of American music, and the foundation of black preaching. Blues is the curve of the Mississippi, the ghost of the South, the hypocrisy of the North. Blues is the beauty of bebop, the soul of gospel, and the pain of hip-hop.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Can we recover a blues sensibility? Do we dare speak with authority in the midst of tragedy? As it is, America is living stormy Monday while the pulpit is preaching happy Sunday. The world is experiencing the blues, and pulpiteers are dispensing excessive doses of nonprescribed prosaic sermons with severe ecclesiastical and theological side effects.

In his book Where Have All the Prophets Gone? Marvin McMickle, president of Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, asks what’s happened to the prophetic wing of the church. Why, he says, have we emphasized a personal ethic congruent with current structures and not a public theology steeped in struggle and weeping? McMickle talks about the focus on praise (or the neocharismatic movements) coupled with false patriotism—enhanced by the reactionary development of the Tea Party, the election of President Barack Obama, and personal enrichment preaching (neoreligious capitalism informed by the market and masquerading as ministry).

The blues has faded from the Afro-Christian tradition. The tradition is lost in the clamor of material blessings, success without work, prayer without public concern, and preaching without burdens. We must recover this blues sensibility. We must regain the literary sensibility of Flannery O’Connor, Ernest Hemingway, and James Baldwin; the prophetic speech of Martin Luther King Jr., William Sloane Coffin, and Ella Baker; along with the powerful cultural critique of Jarena Lee and Dorothee Sölle.

The blues is one of America’s unique and enduring art forms. Its roots are African, but the compositions were forged in the humid southern landscape of cypress and magnolia trees mingling with Spanish moss. It is more than music: the blues is a cultural legacy that dares to see the American landscape from the viewpoint of the underside.

Ralph Ellison states, “The blues is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness. . . . As a form, the blues is an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.”

August Wilson and Zora Neale Hurston, two organic theologians and nontraditional homileticians, capture the essence of blues speech and are chroniclers of black religiosity and the healing power of God-talk as articulated by people who preach and sing in minor keys.

For Wilson, speech wrapped up in the blues is the antidote to the blues. In other words, the only way to get rid of your blues is to speak to your blues. In Wilson’s play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, for instance, the character based on blues singer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey speaks of the blues’ prophetic power to release the individual from spiritual isolation:

The blues help you get out of bed in the morning. You get up knowing you ain’t alone. There’s something else in the world. Something’s been added by that song. This be an empty world without the blues. I take that emptiness and try to fill it up with something.

Ma Rainey is saying, “I refuse to fall into despair.” This is Blue Note preaching. It’s prophetic preaching—preaching about tragedy, but refusing to fall into despair.

Instead of prophetic preachers, however, we have reporters masquerading as prophets. They are announcing tragedy, sending notes of folly and foolishness, and crafting social-media posts about the decadence and demise of our culture. This is not prophetic blues speech; it is shallow reporting and voyeurism designed not to alter the world but to numb our spiritual senses. Over time we accept that The Real Housewives are actually real, even though everything they have is fake; that reality TV is authentic; and that anything shot in high definition video is a documentary. Blues speech rescues us from acceptance and dares us to move from the couch of apathy to a position of work.

Walter Brueggemann says that when we look at the Bible we must “read, speak, and think as the poet.” The academic or news reporter can neither understand the nuance nor conjure the power of prophetic blues speech. Preachers sing songs in major and minor keys and refuse to jettison lament from our vocabulary. We celebrate all life and find the beauty in the midst of the magnificent mosaic of human contradiction. In Psalm 137, the psalmist speaks the blues when the words go forth from the mouths of poets who speak with a blues sensibility. “By the rivers of Babylon, we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion. There on the poplars we hung up our harps, for there our captors asked us for songs, our tormentors demanded songs of joy; they said, ‘Sing us one of the songs of Zion!’”(NIV)

Zora Neale Hurston, Harlem Renaissance writer, folklorist, and novelist, spent her life recording the blues speech and patterns of displaced Africans. Her work claims that people of African descent do not need external cultural validation; they have a rich culture whether or not it is acknowledged by Western scholars.

Hurston takes the speech of southern storytellers, preachers, and singers and peppers her fictional work with their wisdom, creating a rich tapestry of speech where blues sensibilities and call-and-response moments are the norm. In Their Eyes Were Watching God, two characters are taking refuge from a hurricane:

The wind came back with triple fury and put out the light for the last time. They sat in company with the others and other shanties, their eyes straining against crude walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.

The preacher too is to stand through storms after all the lights have gone out and the tourists have left. The call is to stare in the darkness and speak the blues with authority, and witness the work of God in darkness and even in the abyss.

According to Flannery O’Connor, Christian writers are burdened by their knowledge of an alternative world because they have encountered a God of grace and love. But the world that they look at does not fit the alternative world. The writers know what the world should be but are burdened by the divine distance of humanity from divinity. They see “the grotesque,” who are out of sync with God, as well as characters who demonstrate the grace of God even though they are distanced from God. Through this tension the writer is drawn to the grotesque of blues and finds that God is loose in the world.

Isaiah speaks this same blues sensibility with poetic power and prophetic boldness. “Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees, to deprive the poor of their rights and withhold justice from the oppressed of my people, making widows their prey and robbing the fatherless” (10:1–2, NIV). The prophet speaks with poetic language and lifts up the grotesque in the world of Israel.

Billie Holiday expresses the blues sensibility when she sings “Strange Fruit”:

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

black body swinging in the southern breeze,

strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Holiday is singing not to cause the audience to fall into despair, but to empower all who hear. I will not allow you to cover your ears or your eyes, she says. If we are to see a world that is different from the world that is now, I must speak the blues.

In Jesus and the Disinherited, Howard Thurman speaks of Jesus as savior and liberator of those who have their backs against the wall. Obery Hendricks borrows from Thurman and urges us to view Jesus not solely as the sociological savior of oppressed people, but as a person who lived life as a colonized individual. Jesus understands the pain of terrorism and is acquainted with the structures of disenfranchisement that rob people of their humanity.

In other words, Jesus knows all about our troubles.

When the preacher plays, performs, and preaches with the Blue Note sensibility, he or she has the audacity to reclaim Jesus as savior and liberator of marginalized people. The God of the Blue Note empowers men and women and refuses to be categorized by puny, inadequate definitions created by humans and concretized by the academy. It is the role of the prophet/preacher to harness a portion of this divine energy. She seeks to paint a new world with the toolkit of oral performance, imagination, and keen intellectual investigation. In the process she is altered by the heavy elusive nature of the word she carries and can’t help being bruised and blessed by the weight of the sacred task before her. The word leaves marks upon her shoulders, just as bruises were left upon the Israelites who carried the ark across the desert of Canaan. The word cuts and leaves scars upon her body and fissures in her mind, as she seeks to handle what cannot truly be handled.

Maria Wright Stewart, a schoolteacher, activist, and preacher in the 19th century, spoke unflinchingly about being a woman of African descent who was designed by God as a gift but is mistaken by the world as a curse.

The frowns of the world shall never discourage me nor its smiles flatter me; for, with the help of God, I am resolved to withstand the fiery darts of the devil, and the assaults of wicked men. (Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart)

Blue Note preaching is a way of knowing. We refuse to turn away from the beauty in the ashes; neither shall we turn from the ashes that were once a bouquet of beauty: I am African, I am black, I am woman, I am displaced; yet I pull from my sacred toolkit a palette of colors capable of beautifying the decaying walls of my prison. In the process of preaching, we unlock the gates of the prison with a word the world cannot comprehend.

Preachers draw strokes of tone, colors of oratory, and auditory dynamics on a drab canvas of a broken world by using the paintbrush of the word. Christ brings colors, tone, dynamics, chords, and a new time signature. As we paint we can see women and men who have the smell of mud, manure, and magnolia on their feet, standing with dignity as cool red clay presses between their toes and the southern sun beats them with a continual whip of heat and humidity. Can you see upon the tendons stretched beyond capacity the muscles bulging under the weight of rice, cotton, and tobacco?

An entire orchestra was birthed “down by the riverside” as mothers sang, “Roll, Jordan, roll.” A new speech—speech with a conjuring power—stepped into the light. The Blue Note and blues sensibility were born in this place of death that became the place of life. Just as Jesus hung up on the cross and transformed an execution into a celebration, the Blue Note sensibility conjures life from death’s domain. It turns the gospel back to Jesus, the church back to Christ, and the preacher back to the prophets.

When performed by the artist of African descent, Blue Note preaching brings a new vitality to homiletics. Preachers of African descent were born outside of the American project and were forced to gaze through the window of democracy. They yearned and wept for strange gifts that were on display on the other side of the windowpane, gifts with strange names such as “freedom,” “democracy,” “free agency,” “autonomy,” and “humanity.” This distance and yearning gave the preacher of African descent a “second sight.”

A little girl about six years old taught me a wonderful lesson about Blue Note preaching when Trinity Church was going through a very painful moment. My predecessor had been unfairly lifted up and attacked in the media because a person who’d been kissed by nature’s sun was running for the presidency. As a result media were outside of our church everyday. There were a hundred death threats every week: “We are going to kill you. We are going to bomb your church.”

The stress was so painful that it was very difficult to sleep at night. One night I was half asleep and heard a noise in the house. My wife, Monica, punched me and said, “You go check that out.” (Oh yes, it’s OK to laugh.) So I did. Like a good preacher I grabbed my rod and staff to comfort me. I went walking through the house with my rod and staff that was made in Louisville with the name Slugger on it.

I looked downstairs, and then I heard the noise again. I made my way back upstairs and peaked in my daughter’s room. There was my daughter Makayla dancing in the darkness—just spinning around, saying, “Look at me, Daddy.”

I said, “Makayla, you need to go to bed. It is 3 a.m. You need to go to bed.”

But she said, “No, look at me, Daddy. Look at me.”

And she was spinning, barrettes going back and forth, pigtails going back and forth.

I was getting huffy and puffy wanting her to go to bed, but then God spoke to me. “Look at your daughter! She’s dancing in the dark. The darkness is all around her but it is not in her!”

Makayla reminded me that weeping may endure for a night, but if you dance long enough joy will come in the morning. It is the job of preachers to teach the Blue Note gospel, the gospel that sends this word to us in the hardest of times: do not let the darkness find its way in you. Dance in the dark.

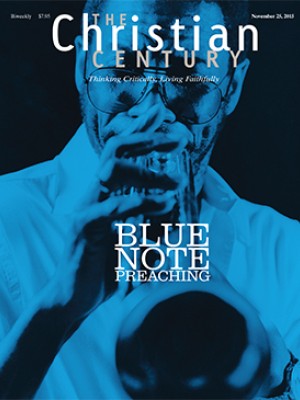

This essay is adapted from Blue Note Preaching in a Post-Soul World, by Otis Moss III, to be published in November by Westminster John Knox, based on his 2014 Beecher Lectures at Yale. © om3. Used with permission of the publisher.