The face of Everyhuman

When I was in elementary school, living in an apartment development on the east side of Manhattan, one of my favorite things to do was to wander among the identical redbrick buildings with clipboard and pencil, stop passersby, and ask them to respond to a survey. The questions I dreamed up were various, but they all had something to do with what it means to be a human being; and I must have seemed innocuous enough, for no one refused my request.

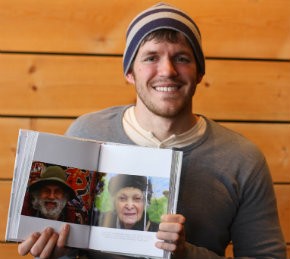

Five years ago an unemployed bond trader named Brandon Stanton created a fully realized version of what I was trying naively to accomplish with clipboard and pencil: Humans of New York, a photoblog capturing the faces, fashions, struggles, miseries, and joys of genus Everyhuman, species New York. If, like me and 15 million other people, you follow HONY on Facebook (the parody site, Orcs of New York, has a mere 20,000 followers), then perhaps you too have been moved to tears by the images and stories, by the endless stream of encouraging comments, and by the empathy-driven crowd-funding projects HONY has inspired. You’re probably also aware that Stanton has taken his special brand of heart-piercing street portraiture beyond New York to Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, Ukraine, India, Nepal, Vietnam, and Mexico. Everyhuman, we discover through Stanton’s lens, is everywhere.

As I write, HUMAN: the movie, a cinematic collage created from 2,000 interviews with men and women in 60 countries, is premiering at the Venice Film Festival, slated to be shown at the 70th session of the UN General Assembly, and available for free on YouTube in a three-volume extended edition.