Is compromise always good?

At the national level, there was only one real question going into the November 4 elections: Would the Democrats keep the Senate? They didn’t. For the next two years, it’s essentially President Obama against Congress. The Senate minority party does have considerable power, and the remaining Democrats may manage to keep some Republican legislation off the president’s desk. But Obama will almost certainly have to do more of something the Senate has until now protected him from: choose between signing Republican bills and vetoing them.

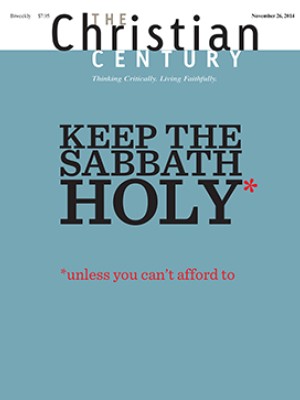

Would compromise be better than gridlock? It sounds like an easy question. We want our elected officials to actually accomplish something. As Christians we are keenly aware of the importance of coming together for the greater good. Amid deep division, the alternative to compromise—inaction—seems like outright failure.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The problem is the assumption that a compromise position is an improvement on the status quo. This isn’t always the case.

To be sure, it often is. Getting the Affordable Care Act passed required the bill to be watered down, convoluted, and larded with perks for the very industries that have helped make U.S. health care such a mess. Yet the 2010 law was a clear step forward, enabling millions of uninsured Americans to get coverage. Or take our broken immigration system. A compromise bill that includes even incremental steps toward a path to citizenship would directly improve the lives of families living in this country. Middle-ground bills can be good ones.

But not always. During the Clinton administration, a divided government compromised to enact welfare reform. While the 1996 law has been praised for replacing simple cash assistance with “welfare to work,” it also replaced a program that helped 12.6 million low-income Americans with one that currently serves about 4 million. For the millions who lost their benefits, gridlock would have been better. This year’s farm bill debate hinged on the question of whether to make small cuts to food stamps—the bill’s largest and most unambiguously useful program—or to make larger ones. While the farm bill is a complex thing with many stakeholders, for the hungry at least, inaction may have been the best option on the table.

In our two-party system, it’s tempting to believe that the best ideas lie somewhere in between. But compromise is not itself an adequate ethical yardstick for judging legislation. We Christians have other, better standards. What serves the common good? What promotes human flourishing? Sometimes the best answers come from the middle. Other times they might come from one side or the other, or even from the margins of mainstream discourse.

The next two years will offer many opportunities for elected officials to choose whether to meet in the middle. We should demand that they work within the political constraints to pursue a more just and fair society—both when this means accepting compromise and when it means accepting gridlock.