The wall of identity: Resident Aliens at 25

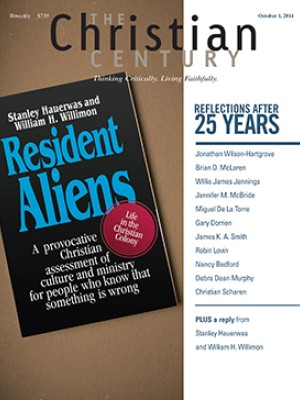

In 1989, Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon sparked a lively debate about church, ministry, and Christian identity with their book Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony. Twenty-five years later, we asked several pastors and theologians to offer their perspective on the book and its impact. (Read all responses.)

I always appreciated the effect that Resident Aliens had on students. It gave them confidence to take the church seriously as the place in which and from which to imagine their lives and work in the world. This theological manifesto captured so much of the gestalt of Hauerwas and Willimon—their lighting quick wit, their relentless slashing of liberal Protestant sensibilities, their trenchant diagnosis of the identity crisis of mainline Christianity, and their inspired vision of the politics of God made manifest in the body of Jesus.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The book also captured the feel of the times at the tail end of the Reagan revolution, along with the retreat of progressive coalitions and politics and the rise of a new class of intellectuals who would come to be called neoconservatives. In fact, the book had the feel of the neocon texts that were emerging at that time. It paralleled their critique of liberalism, their diagnosis of a fading moralistic American identity, and their demand for a disciplined role for government.

Resident Aliens was not a neoconservative text, although some read it that way. It was, however, quintessentially an American text. The book affirmed the strange way we Americans deal with our racial history and its current realities by indirection, innuendo, and avoidance. Black people remained a subtext, an unspoken backdrop for narrating the Constantinian problem. Even in his preface to the 25th anniversary edition, Willimon, without ever reflecting on the racial complexities of Obama’s presidency or of his faith, chides United Methodist bishops for their deferential focus on the president. Avoidance continued. Resident Aliens told a generation that they could make church-state issues intelligible in America without seeing how race is tightly woven through that relation.

The book also presented a romantic notion of church practices inside a detached vision of formation. The book told students that church practices are identity forming, which for some was news but for many simply affirmed their precritical piety and exaggerated their focus on the sacraments. The idea of formation in Resident Aliens ignored decisive racial, class, and gender formations and gave little help in seeing their interplay. Its vision of practice was impotent in helping grasp the social conditions within which practices are always embedded.

To its credit, the book gave us a more finely grained view of the church-world distinction. Yet here it was haunted by a narrative of social decline fueled by white anxiety. The charge of sectarianism never stuck, but the charge that its version of Christian identity was protectively closed and fed into America’s segregated sabbaths did. It gave us an idea of Christian identity as a wall with a door and not a door in a wall. This is no minor difference, because it pivots on the barrier-breaking body of Jesus, who brings together those who would prefer to stay separated and places confidence in us to do the same.