The politics of deportation

On election day, the Republicans will almost certainly retain control of the House of Representatives. The Democrats may lose the Senate. And 1,000 more undocumented immigrants will be deported.

That’s the current daily average, and the Obama administration recently announced that it will wait until after the November midterms to do anything to change this. Previously, the president promised executive action to protect immigrant families, given Congress’s failure to take up immigration reform. Now those families will have to wait—and perhaps be deported.

A White House official told the New York Times that acting too soon would be unsustainable, even “harmful to the policy itself.” Left unsaid: Obama is trying to help Democrats in close Senate races by declining to add fuel to their opponents’ fire.

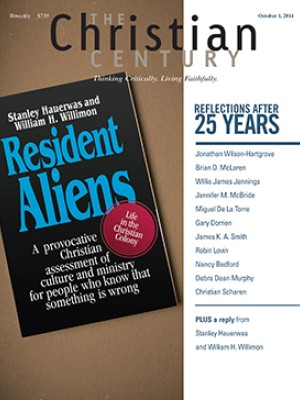

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The reaction from pro-immigrant activists has been fierce. They rightly point out the human costs of Obama’s decision: thousands of people deported between now and election day, thousands more living in fear that they might be next. Hardworking taxpayers will be kicked out, people whose only crime is coming here. Spouses will be separated and families broken up. Faced with a choice between the welfare of these families and his party’s political advantage, Obama chose the politics. People will suffer as a result. And it’s far from guaranteed that the administration’s implicit claim—that a Democratic Senate is the best chance for lasting immigration reform—will pan out.

But it might, of course. And either way, it’s worth noting that this sort of retreat from a worthy cause is a predictable consequence of a political system gone wrong. It’s Obama at his least inspiring and most pragmatic, letting down vulnerable families now in favor of helping his party possibly do more good later. But it’s also a symptom of what’s wrong with Washington.

Our political system is as broken as our immigration system. A June poll found that 62 percent of Americans—including 51 percent of Republicans—favor a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Yet Congress remains unmoved. The House, after all, doesn’t answer to national majorities; population patterns and gerrymandering have left it disproportionately beholden to right-wing constituencies. Whatever working consensus might be reached in the Senate is kept at bay by the filibuster. Legislators risk far more by defying their own party’s hardliners than they do by ignoring the will of the people generally. And they have even less incentive to cooperate with an opposition president. Obama’s left choosing whether or not to take controversial executive action where Congress has shirked its duty.

For now, he’s choosing not to. It’s a devastating development for those immigrant families it will affect directly. It’s also a disappointing one for anyone who still thinks Obama has the power to transcend partisan politics. He doesn’t—and in recent years he has behaved less like a reconciler in chief and more like a tough party leader in a broken, ultrapartisan age. But Obama didn’t break our politics. And it isn’t his fault that Congress lacks a compelling incentive to pass immigration reform most Americans want.