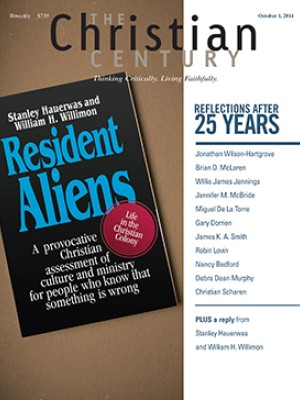

Better religion: Resident Aliens at 25

In 1989, Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon sparked a lively debate about church, ministry, and Christian identity with their book Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony. Twenty-five years later, we asked several pastors and theologians to offer their perspective on the book and its impact. (Read all responses.)

Several years ago, when the Baptists of North Carolina decided to take a stand against homosexuality, the new preacher at a church in my hometown excommunicated Gene. The pastor’s case was simple: Gene was, as everyone knew, gay. North Carolina Baptists had just made it clear that being gay was a sin. Therefore the church had to distance itself from Gene.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I wasn’t there to witness the proceedings, but the result was swift: Gene was no longer welcome in the church that had raised him.

Counties don’t get any redder than that little corner of North Carolina where Gene and I grew up. I can’t imagine that Gene ever felt affirmed as a homosexual in school, on the Little League field, or at church. But in that little congregation where his daddy played the organ and his uncle chaired the board of deacons, Gene had always had a home. People who read their Bibles and loved Jesus also loved him. Maybe this love for their native son was radical, but they never stopped to think about it until a preacher whose religion made him morally worse came along.

I understand Hauerwas and Willimon’s Resident Aliens as a response to the sort of civil religion that makes people morally worse than they would be otherwise. Hauerwas and Willimon both grew up during the civil rights movement, when people like Clarence Jordan were being excommunicated for fellowshiping with black people. In such a context, the words of the prophets ring true. We cannot live at ease in Zion. We must acknowledge that God’s people are aliens and strangers in a strange land.

Resident Aliens tried to show that this problem at the heart of southern religion is endemic to American Christianity. Two southerners held a mirror up to the church and said, “Y’all have a look. To everyone else in the world, you don’t come off much better than a Mississippi Klansman.”

Or rather, that’s what they might have said. Instead, they took on the ideologies they saw propping up American civil religion—liberalism, democracy, and Christendom. Resident Aliens made space for a conversation about how being a good Christian might be different from being a good American.

But I wonder if the attempt to make us less American has made it more difficult for some of us to see that the problem at the heart of southern religion belongs to all of us. Yes, we need communities of character to form people in the virtues. But we can’t simply opt out of our inherited contradictions. However alien the gospel may make us, its power in the world depends on us remaining resident—awkwardly present in compromised churches like Gene’s, where corrupted religion threatens to make us worse.

My guess is that two or three would have been enough to turn the tide against that new preacher. If Resident Aliens is right, then the future of American Christianity may depend on such as these.