When the Westerners leave

In several scenes of the movie Blended, starring Adam Sandler and Drew Barrymore, an all-male singing group accompanies shots of the movie’s characters and punctuates the plot. “Welcome to Africa,” the group sings as families arrive at a resort in an unnamed African country. “We are blending!” they sing, as American stepfamilies participate in family bonding exercises. Terry Crews, an American football player, leads the singers in what looks like an addled recollection of a minstrel show. The result is a movie that presents an American idea of Africa, one that’s embarrassing and desperately in need of revision.

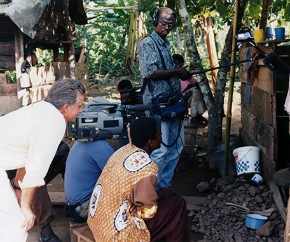

Blended’s producers should have looked at James Ault’s two-part documentary African Christianity Rising. Ault is an ethnographer and filmmaker whose 1987 Born Again offered an intimate portrait of American fundamentalism. He filmed in Zimbabwe and Ghana over a period of almost 20 years and depicts each country in its ordinariness. Each of the two parts leaves you with the feeling that you’ve been to the place—you can feel the dust on your feet.

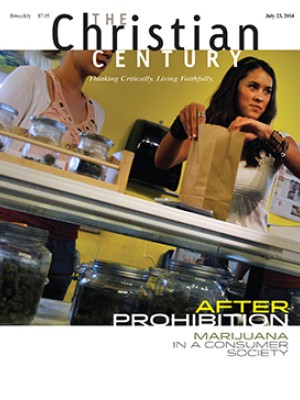

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

One person Ault interviewed notes that Westerners have come to Africa to teach for millennia and that perhaps now they should come to learn. Ault does just that. He walks and talks with theologian Kwame Bediako through a former mission district in Ghana. We see the streets they walk on, the kids playing, the mopeds and the traffic jams, the banks and the billboards. This Africa is not made into an exotic myth. On the contrary, Ault narrows the view to one country, one town, and one specific history.

Churches are flourishing across Ghana, from Presbyterian to Pentecostal megachurches and minichurches to Roman Catholic churches with masses featuring drumming and dancing. All of them share the particularities of their cultural contexts: they all have healing ministries, perform exorcisms, and include dancing and music local to their contexts. One church had an organ (Presbyterians, of course!), but even that church includes exorcists.

In their rush to make something of Africa (or market something to Africa), Westerners have often either looked down on Africans or idealized them as spiritual saviors. But in Ault’s documentary, we hear Pentecostal pastors in Ghana who punctuate every sentence with “Hallelujah.” They tell Ault that every week they visit people and invite them to come to church and that every week their strategy fails—except for the week when they didn’t have time to do their visits. The next Sunday the church was full. “I suppose it really is God’s work,” one pastor said. I couldn’t help wondering if the presence of an American camera crew had something to do with the larger crowd.

Ault interviews a Roman Catholic bishop who says that religion in Ghana is like the human skin. “We take it with us wherever we go.” There is no division between sacred and secular, body and spirit. A long montage of exorcisms is accompanied by a speaker who says that exorcism is “practical Christianity.” Nothing could be more physical.

At this point American liberals get nervous. Surely the people shrieking in the aisles are performing or mentally ill or just plain weird. But our African colleagues are more biblical than many of us. I’ve heard it said that if Jesus had a business card, it would read “First-Century Jewish Exorcist.” And there’s hardly a page in the Gospels where Jesus is not casting out a demon. The Africans in Ault’s film know about modern medicine. They have cell phones pasted to their heads just as we do. And they still think that demons are loose in the world causing mayhem and individual enslavement and that Jesus is the answer.

I don’t know what to make of that. But the challenge it poses to me is much more interesting than Terry Crews’s flexed pectorals in Blended.

We North American and European Christians have done a half century or more of hand-wringing about the missionizing and evangelizing we undertook in Africa, Asia, and South America. Books like The Poisonwood Bible and movies like The Mission memorialize our mistakes. Christianity is seen as intolerant, bulldozing, ignorant, destructive of ancient customs, naive at best, and demonic at worst. Yet when Western influence wanes, Christianity flourishes. Christianity did not flicker and die with the end of colonialism; instead, the places we left became more Christian. In South Sudan, for example, the expulsion of American missionaries led to an explosion in church participation with indigenous leadership.

The Catholic bishop (dressed in Roman vestments) in Ault’s “Stories from Ghana” chuckles when he says that Western culture was like the envelope in which a letter was received. The gospel was the letter. “We have received the letter and thrown the old envelope away.” At first his fellow Ghanians thought that drums and exorcisms would ruin the church. Now his diocese is a model for indigenized Christianity.

Ironically, local cultures are better sustained by Christianity than by other Western imports such as Hollywood. Sometimes the missionaries’ first motives are to translate scripture and to make converts. But to do this they learn languages and also eat food, attend events, and are present at the births and deaths of their neighbors. If they do any of these things well, the missionaries themselves are changed. As they change, the church as a whole also changes.

Perhaps it is absurd to compare Christianity at its relative best to Hollywood at its relative worst. Movies like Blood Diamond and Captain Phillips have a shot at widening our empathy, and they don’t pile on absurd stereotypes. But it’s refreshing to stop once in a while and realize that Christianity does not need us Westerners in order to thrive.